[ad_1]

I reach that program director, Jonathan Crane, DO, via email. “My approach towards residents educating the public has always been supportive,” he says, as long as those residents are forthright, and, of course, acing their tests. Dr. Crane doesn’t put any restrictions on his residents’ social media presence, even if — as in Dr. Shah’s case — skin-care or pharmaceutical companies come knocking with paid opportunities.

When asked by other program directors about his you-do-you social media policy, “I typically explain how well the resident is performing during their training,” Dr. Crane says. “What reason would I have to stop them when it’s educating the public and saving lives?” He points out that Dr. Shah was honored with the Melanoma Research Foundation’s Influencer Award in 2021.

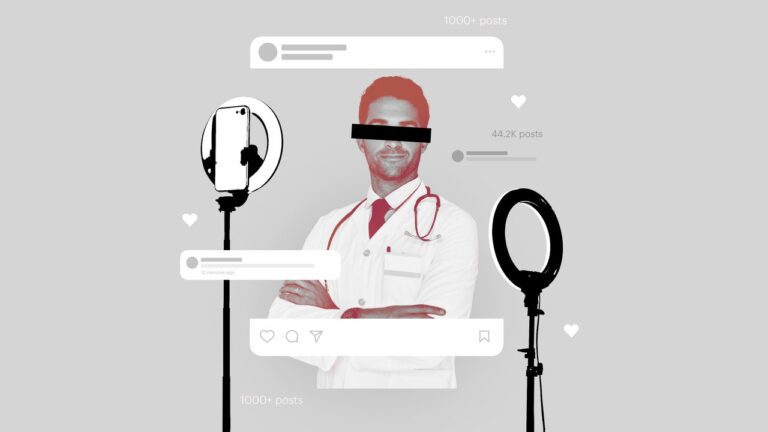

Though Dr. Shah began his career online as a resident, he cut a more authoritative figure with series like Dermatologist Reacts, featuring his split-screen reactions to viral videos, and the handle @dermdoctor. In 2020, after Dr. Shah made a video recommending an Inkey List product, the brand reached out with an offer for what would become his first paid advertisement. By the time Dr. Shah attained board certification, in 2022, his partner roster read like walking down a drugstore’s skin-care aisle — CeraVe, Neutrogena, Olay. Dr. Shah declines to comment on how much he makes per sponsored post. “If I wasn’t a doctor, I would,” he explains, but wonders whether it’s unprofessional to share.

In response to critics who say that some dermfluencers don’t spend much time seeing patients, Dr. Shah says that, in his case, respectfully, they’re wrong. “For me, it’s just not true,” he says when we connect in late February. He was recently in New York, he adds, where he was performing hair transplants at Hudson Dermatology.

He does travel often, but Dr. Shah says that New York City is his full-time residence. He will be seeing patients in Manhattan for a week in March, he tells me, and later updates that to two weeks, explaining that because of his travel schedule, appointments are usually not booked far in advance. He says he hopes to ramp up his availability this year.

“If I had to choose between content and dermatology, I would choose seeing patients every day,” says Dr. Shah. But he doesn’t look down on dermatologists who have opted out of patient practice in favor of social media work. “I think a lot of people that only do social media and don’t see patients, it’s probably because they found out they didn’t really enjoy it,” he says. Maybe they have social anxiety, kids at home, fear of germs. “I almost feel like, who am I to judge?”

Doctors are not obligated to disclose how much time they spend in examination rooms or labs, let alone making videos for TikTok. And they only have a few obligations to disclose how much they are paid for promotional or consulting services. A 2010 law known as the Physician Payments Sunshine Act allows Americans access to a database that records payments between drug companies, physicians, and teaching hospitals. Querying any one of the three opens a ledger of payments for things like consulting, lodging and travel, honoraria.

But cosmetics are distinguished from drugs in the eyes of the Food and Drug Administration, and skin-care companies are not obligated to publicly disclose, say, how much they paid a dermatologist for partner content. For their part, doctors are beholden only to the same disclosure regulations that govern all influencers, put forth by the Federal Trade Commission: Use clear and concise disclosure language, like “sponsored” or “partner.”

A lack of comprehensive regulation and full transparency has driven some doctors to establish their own boundaries. When a major company asked one veteran dermatologist to be on an advisory board regarding a topic on which she had authored research, she was interested in the gig — until she found out that another member of the board was a dermatologist who made videos instead of seeing patients. The veteran dermatologist dropped out. “I’m not doing this advisory board, which is going to lead to a major publication,” they fumed. “I’m not giving the credibility to people who are not working.”

Skin-care companies are incentivized to work with dermatologists early on, even during residency. In these relationships, the trainee functions less like an expert and more like a host, and the brand has greater editorial control over the resulting paid content. Whether or not a dermatology resident is an eligible dermfluencer varies from program to program. At George Washington University, it is “completely forbidden” for a resident to “promote, support, recommend, or suggest the use of either prescription or over-the-counter products on social media,” according to the program’s two-page social media policy. Johns Hopkins Medicine permits employees, including residents, to engage in social media partnerships as long as they don’t invoke the Johns Hopkins Medicine brand. (We contacted 10 other prominent dermatology residency programs; most either declined to comment on their social media guidelines or did not respond.)

[ad_2]