[ad_1]

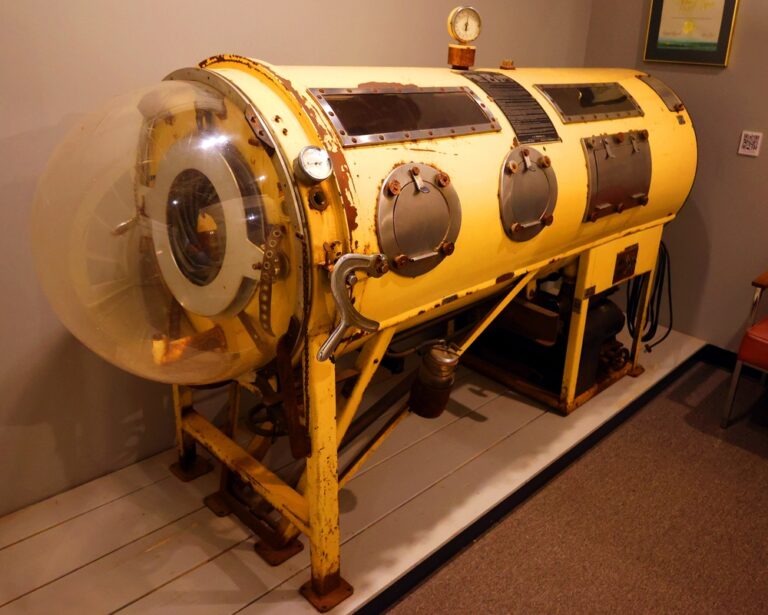

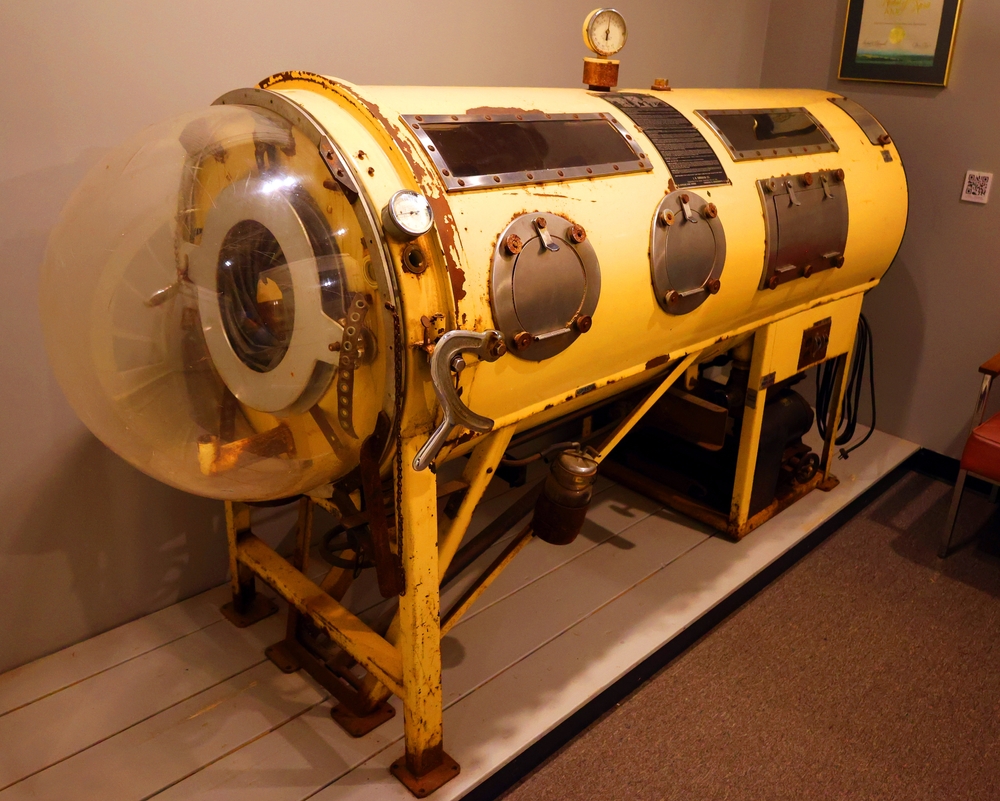

In medical and engineering circles, it’s known by a few different names: cabinet respirator, tank respirator, negative pressure ventilator and others.

But since its creation almost a century ago, this lifesaving device has been known almost universally by another name: the iron lung.

What Is an Iron Lung?

As intimidating as the name sounds — and as scary as the coffin-like device looked — the iron lung was a medical miracle for people suffering from something even scarier: poliomyelitis. Before the polio vaccine was invented in 1955, the virus could be a death sentence, and periodic epidemics filled people around the world with a dread that’s hard to imagine today, even in a post-COVID world.

In addition to flulike symptoms, polio was known to cause muscle stiffness and paralysis. If the virus paralyzed muscles in the chest, polio sufferers — most of whom were children — couldn’t breathe. Most patients would recover all or most of their muscle strength if they could just survive this critical phase. The challenge was to figure out a way to keep them breathing for the one to two weeks that they typically needed to recover muscle function.

How Does an Iron Lung Work?

(Credit: Penlite CC-SA 4.0 Wikimedia Commons)

Thus, the iron lung was developed in 1927 and first used in a clinical setting in 1928, saving the life of a stricken little girl — and what would soon be many thousands of others. It was invented at the Harvard School of Public Health by Philip Drinker with Louis Agassiz Shaw. Drinker in particular had been studying therapies for coal-gas poisoning but realized the form of artificial respiration that culminated in the iron lung could help polio victims as well.

Drinker envisioned an airtight chamber (typically made of steel, not iron, by the way) into which a patient could be placed. Their head remained outside the chamber while a rubber collar kept the enclosure sealed. The first iron lung was basically powered by an electric motor and the air pumps from a couple of vacuum cleaners.

The respiration chamber functioned via external negative pressure ventilation (ENPV). Air would be sucked out of the chamber, which would cause a patient’s chest to expand, filling the lungs with precious oxygen, even when the patient’s muscles were incapable of doing so. Then, air would be let back into the chamber, causing the lungs to deflate and allowing the patient to exhale. The motor kept the pumps operating, and more importantly, kept the patient alive. The process by which the iron lung functioned was simple and effective.

Read More: The History of the Polio Vaccine

The Evolution of the Iron Lung

But the devices themselves posed some challenges. Getting patients into and out of early iron lungs was cumbersome. And the chambers were expensive, costing between $1,500 and $2,000, or about the same price as the average suburban home back then. They could also weigh as much as 500 pounds apiece and were a logistical nightmare to transport even within the U.S., let alone around the world.

Various design changes were implemented over the years to make patient access easier and also to make the construction and deployment of iron lungs faster and cheaper. During a polio outbreak in Australia, which literally couldn’t get standard iron lungs shipped fast enough, an engineer named Edward Both built a prototype “iron” lung using plywood, one that could be constructed and ready for use in a day.

Mass distribution of iron lungs began in the late 1930s. By the late 1950s as many as 1,200 people in the U.S. alone were using iron lungs. Not every polio sufferer was lucky enough to regain breathing function in a couple of weeks. Some patients — about 1 in 200 — suffered permanent muscle and lung damage and would have to use iron lungs on a more or less permanent basis. However, with the advent of the polio vaccine, and the invention of newer forms of mechanical ventilation, the iron lung gradually became obsolete. At least for a while.

Read More: What Would Happen If We Didn’t Have Vaccines?

Are Iron Lungs Still Used?

(Credit: FDA/Public Domain)

Some few polio survivors still use old-school iron lungs. According to Guinness World Records, for example, Paul Alexander is a polio survivor who has used an iron lung since 1952, when he was stricken by polio at the age of 6 in Dallas, Texas. Although he learned breathing techniques to help reduce his reliance in the chamber, he still spends a significant part of his day in the iron lung.

It’s a challenge for the scant few iron lung users remaining to maintain their constant use of the once cutting-edge respirators. Replacement parts are hard to come by, as is finding anyone still versed in their maintenance and repair. Yet they continue to try to find ways to keep their chambers operating, believing that the old-fashioned iron lungs still provide better therapy and comfort than modern ventilators.

What Replaced the Iron Lung?

During the COVID pandemic, various doctors and engineers did “reinvent” the technology, developing new pressure ventilators that could save patients without requiring them to be intubated on ventilators that were much more likely to cause permanent respiratory damage. This development may aid future patients in need of respiratory help from new and emerging diseases.

But hopefully it won’t be needed for future polio victims. The World Health Organization remains committed to eradicating the virus. Today, polio cases worldwide have fallen from around 350,000 cases in the 1980s to just six reported cases in 2021. As polio dwindles, perhaps we can breathe a sigh of relief that the need for the iron lung will also diminish at last.

Read More: The Deadly Polio Epidemic and Why It Matters

[ad_2]