[ad_1]

Massive global volcanism that covered 80% of Venus’ surface in lava may have been the deciding factor that transformed Venus from a wet and mild world into the suffocating, sulfuric, hellish planet that it is today.

The surface temperature on Venus is a sweltering 867 degrees Fahrenheit (464 degrees Celsius), hot enough to melt lead, and there’s a crushing pressure of 90 atmospheres underneath the dense clouds of carbon dioxide laced with corroding sulfuric acid. Often decried as Earth‘s “evil twin,” Venus is a victim of a runaway greenhouse effect, no doubt amplified by Venus being about 25 million miles (40 million kilometers) closer to the sun than Earth and therefore receiving more heat.

Yet, there’s growing evidence that Venus wasn’t always this way, and could have once been a temperate world somewhat similar to Earth — perhaps more recently, in geological terms, than expected.

Related: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe captures stunning Venus photo during close flyby

Michael Way, of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, has led much of the research developing this new vision of Venus. In their latest paper, he and his team argue that Venus’ volcanism could have ultimately been what pushed the planet over the edge by sending vast amounts of carbon dioxide — as we know, a potent greenhouse gas — billowing into Venus’ atmosphere.

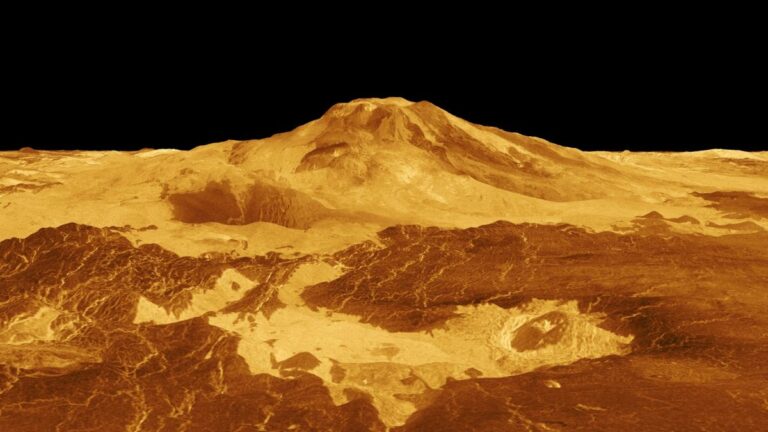

In the 1990s, NASA’s Magellan spacecraft radar-mapped the surface of Venus, which is otherwise obscured by the planet’s dense atmosphere, and found that much of the surface was covered in volcanic basalt rock. Such “large igneous provinces” are the result of tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of years’ worth of massive volcanism that occurred at some point in the past billion years.

In particular, several of these events coming in the space of a million years, perhaps, and each covering hundreds of thousands of square miles or kilometers in lava, could have endowed Venus’ atmosphere with so much carbon dioxide that the climate would have been unable to cope. Any oceans would have boiled away, adding moisture to the atmosphere, and because water vapor is also a greenhouse gas, accelerating the runaway greenhouse effect. Over time, the water would have been lost to space, but the carbon dioxide, and the inhospitable world, remained.

“While we’re not yet sure how often the events which created these fields occurred, we should be able to narrow it down by studying Earth’s own history,” Way said in a statement.

The frequency with which massive volcanic events forming large igneous provinces have occurred on Earth implies that it is likely that several such events could have occurred on Venus within a million years. These incidents could have scarred Venus forever.

Earth itself has had some close calls. So-called “super-volcanoes” have been connected to numerous mass-extinction events on Earth over the past half-a-billion years. For example, the Late Devonian era mass extinction 370 million years ago has been attributed by some to super-volcanism in what is now Russia and Siberia, as well as to a separate super-volcanic eruption in Australia. The Triassic–Jurassic mass extinction is widely blamed on the formation of the biggest of Earth’s large igneous provinces, the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province, 200 million years ago. Even the death of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago may have been caused by the double whammy of an asteroid strike and super-volcanism in the Deccan Traps, a large igneous province in India.

For unknown reasons, similar volcanic events on Venus were much more widespread and instigated a runaway greenhouse effect that transformed the planet. Meanwhile on Earth, the carbon-silicate cycle that acts as the planet’s natural thermostat, exchanging carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases between the mantle and the atmosphere over millions of years, was able to prevent Earth from following the same path as Venus.

Two future NASA missions will endeavor to answer some of these questions. DAVINCI, the Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble Gases, Chemistry and Imaging mission will launch later this decade, to be followed by VERITAS, the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography and Spectroscopy mission in the early 2030s. The European Space Agency’s EnVision mission also targets launch sometime in the 2030s, while China has proposed a possible mission called VOICE, the Venus Volcano Imaging and Climate Explorer, that if launched would reach Venus in 2027 to study the planet’s atmosphere and geology.

“A primary goal of DAVINCI is to narrow down the history of water on Venus and when it may have disappeared, providing more insight into how Venus’ climate has changed over time,” Way said.

The findings were published in the Planetary Science Journal earlier this year.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]