[ad_1]

During the past week, the day-to-day weather outlook for the total solar eclipse on April 8 has been changing.

Although modern numerical weather prediction systems are marvels of science and technology, forecasts made beyond a week in advance are subject to significant changes as new information is ingested into later simulations.

But now, as the days to totality have dwindled to a precious few, these forecasts are now showing increasing signs of converging, providing useful, consistent guidance for which broad areas along the path of totality have the best chance of good viewing conditions.

Related: What happens if it’s cloudy for the April 8 solar eclipse?

These can be augmented by forecasts issued by National Weather Service forecast offices located near and along the totality path. In the final hours before the eclipse, the very latest meteorological data, including careful scrutiny of satellite images and radar scans should be used to modify final observing plans.

And those who would like to peruse various computer guidance models should take advantage of a great weather primer, “Weather Planning for Eclipse Day” by Canadian meteorologist Jay Anderson.

Not what was expected!

The overall pattern certainly does not reflect what long-term climatology averages have suggested. Many who consulted these values from a year or more ago, immediately placed their hotel and airline reservations down for Mexico and Texas and did not give much consideration to New England and Atlantic Canada. But climatology, while quite useful, is not absolute. In his 1973 novel, Time Enough for Love, science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein came up with the following aphorism: “Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get!“

And indeed, the outlook for eclipse day shows that climatology has been practically turned upside-down, with Mexico and Texas showing quite unfavorable conditions for Eclipse Day, while New England and Atlantic Canada, for the most part, suggesting favorable sky conditions for eclipse watchers. But the latter case is not too surprising. In a Feature Article that I penned for the November/December 2023 issue of “Weatherwise” magazine, I commented, “April weather is extremely variable and changeable, so at any location, there is some hope of very clear skies on eclipse day.”

In addition, I was never really impressed by the seemingly favorable cloud statistics for Texas. In fact, in that same article, I pointed out that, “The weather outlook from Texas through the Deep South looks marginal and going from the Ohio Valley and points north, downright unfavorable; the chances of seeing the eclipsed sun at any given moment on April 8 from Texas to Indiana is about 55-60%. These conditions are somewhat better than those for the Northeast United States, Ontario, Quebec, and Atlantic Canada, but, surprisingly, not that much better.”

Weather map for April 8

That having been said, the weather maps for Eclipse Day depict a ridge of high pressure extending south from New York State to the outer banks of North Carolina. Low pressure is centered over Iowa with associated frontal systems extending through central Illinois, southeast Missouri, Arkansas and into central Texas. Another area of low pressure is forecast to be over southwest Texas.

A proliferation of clouds

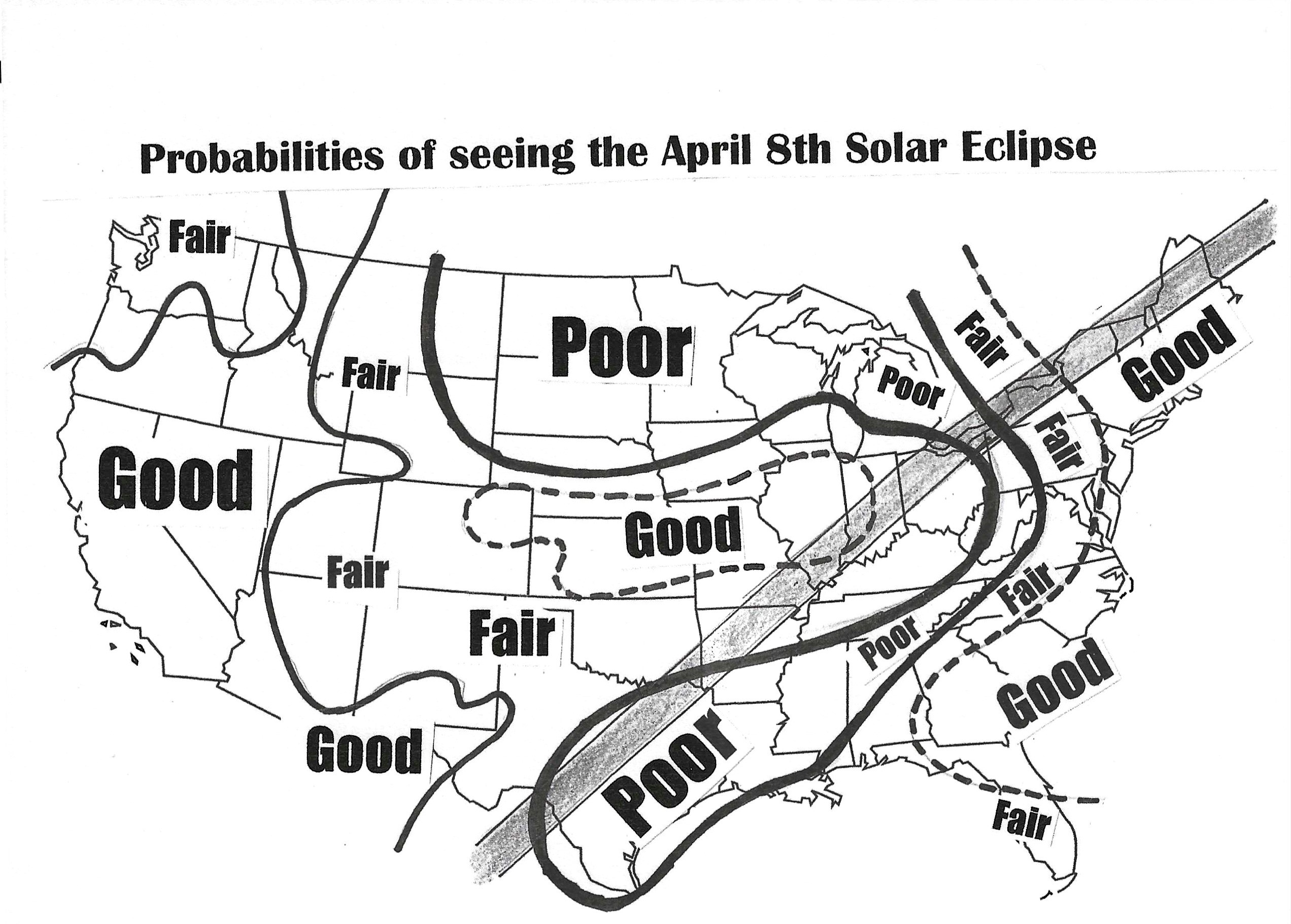

Consulting our Space.com cloud probability map (above), we find that along the path of totality, widespread low cloud cover is being indicated across much of the Texas totality zone. This opaque cloud cover, however, might thin out a bit, possibly allowing for some dim views of the sun for the eclipse track that extends northeast through southeast Oklahoma, the northern half of Arkansas, southeast Missouri, southernmost Illinois, parts of extreme southwestern and eastern Indiana, as well as western and northern Ohio. Northeast Ohio and northwest Pennsylvania might be plagued by a lower/thicker deck of clouds.

Stay mobile!

Those, who have mobility and can take advantage of last-minute “seat-of-the-pants weather updates,” should pay close attention on eclipse day to satellite images over south-central Illinois and western Indiana, where cloudiness could fortuitously thin to just scattered high-level cloudiness or even perhaps mainly clear skies. Of course, even a slight layer of cirrus cloudiness would interfere with viewing the outermost parts of the corona, and yet a considerable amount of detail can still be seen through a layer of thin cirrus or perhaps even a layer of thin cirrostratus.

Similarly . . . a swath of high-to-mid-level cloudiness will likely be advancing into western New York at eclipse time. Generally speaking, such clouds tend to “spill over” the top (or center) of an upper-level ridge of high pressure.

In recent days, the various computer guidance models have been positioning the axis of this high-pressure ridge anywhere from just west of the Hudson River Valley to as far west as the NY/PA border. So right now, the best compromise would be to assume that by eclipse time some high cloudiness could reach as far east as central New York (Watertown to Syracuse). But more often than not, high clouds tend to spread east faster than the models suggest, so it would not be at all surprising if, in the end, they spread as far east as Montreal-to-Burlington.

Where to get the very best views

A professional astronomer or astrophotographer whose success depends on a pristine clear sky should consider the eclipse path running from the northeast corner of New York State, through northern Vermont, northern New Hampshire, northern Maine and possibly as far east as New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia. . . the farther east, the better. Some cloud cover statistics show ranges as low as 15 to 30% in these areas.

Newfoundland, however, could be adversely affected by the same storm system currently affecting the Eastern US; by Eclipse Day this system will be located just southeast of the Avalon Peninsula and could bring cloudy/windy and rainy weather to that province.

Parting thoughts

Two final comments: NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center is forecasting a 15% probability of severe weather on April 8, for much of central and eastern Texas, (including the Dallas-Fort Worth and Austin areas), southernmost Oklahoma, a slice of northwest Louisiana and south-westernmost Arkansas; a region that is populated by over 12 million people. Any potential severe weather that develops in this region would likely wait until after the lunar umbra has passed by but could prove problematic for those heading home after the eclipse.

Lastly, is the topography of upstate New York, Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. The Adirondacks, Green, White and Longfellow Mountains could very well generate convective (cumulus) clouds by midday and afternoon; by eclipse time much of the sky might be covered by these big, billowing clouds. I’m sure, however, that during the roughly 75 minutes of growing partial eclipse, the reduction of sunlight and falling temperatures will cause most of these clouds to dissipate . . . but there is always the chance of a lingering stray cumulus cloud crossing in front of the sun at the wrong moment.

Good Luck to all!

Submit your story and photos! If you capture a photo of the April 8 total solar eclipse or any of these strange effects and would like to share it with Space.com’s readers, send photos, videos, comments, and your name, location and content usage permission release to [email protected].

[ad_2]