[ad_1]

In the millions of years over which humans have been evolving, brain size has tripled, and behavior has become exponentially more elaborate. Early, small-brained hominins (members of the human family) made only simple stone tools. Later, brainier ancestors invented more sophisticated implements and developed more advanced subsistence strategies. As for behavioral complexity in our own eggheaded species, Homo sapiens, well, we went all out—developing technology that carried us to every corner of the planet, ceremonially burying our dead, forming extensive social networks and creating art, music and language rich in shared meaning. Scientists have long assumed that increasing brain size drove these technological and cognitive advances. Now startling new discoveries at a fossil site in South Africa are challenging this bedrock tenet of human evolution.

Researchers working in the Rising Star cave system near Johannesburg, South Africa, report that they have found evidence that the small-brained fossil human species Homo naledi engaged in several sophisticated behaviors that were previously associated exclusively with large-brained hominins. Describing their findings in three papers to be published in the journal eLife, they contend that H. naledi, whose brain was around a third of the size of our own, used fire as a light source, went to great lengths to bury its dead and engraved designs that were probably symbolic in the rock walls of the cave system. The findings are preliminary, but if future research bears them out, scientists may need to rethink how we became human.

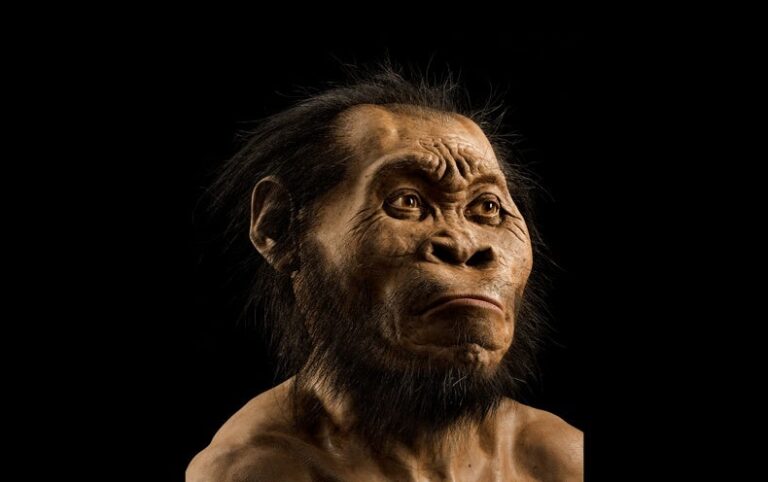

H. naledi is a relatively recent addition to the pantheon of known hominin species. In 2013 and 2014 a team led by paleoanthropologist Lee Berger of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, now a National Geographic explorer in residence, recovered more than 1,500 fossil specimens belonging to at least 15 individuals from deep within Rising Star. The fossils revealed a hominin with an unexpected combination of old and new traits. It walked fully upright like modern humans do, and its hands were dexterous like ours. But its shoulders were built for climbing, and its teeth were shaped like those of earlier hominins in the genus Australopithecus, explains team member John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Most striking of all, H. naledi had a brain size of just 450 to 600 cubic centimeters. For comparison, H. sapiens brain size averages around 1,400 cm3. Berger and his team announced the discovery as a species new to science in 2015. Two years later they were able to establish the age of the fossils, dating them to between 335,000 and 236,000 years ago—surprisingly recent for a species with such a small brain and other primitive traits.

Controversy has roiled around H. naledi from the outset. The remains were found in parts of the cave system that are incredibly challenging to access today and that, as far as the team knows, were just as difficult to reach back when H. naledi visited. Hardly any bones of medium or large animals are known from the site, as might be expected if creatures, including H. naledi, unwittingly fell into the cave. And according to the discovery team, the site lacks any evidence that the bones were transported by rushing water. The implication, Berger and his collaborators argued, was that H. naledi individuals entered this subterranean cave system deliberately to deposit their dead. If that were the case, they must have used a light source—namely fire—to navigate Rising Star’s dark and treacherous tunnels, chutes and chambers. But mortuary behavior and control of fire have long been considered the exclusive purview of larger-brained hominins. Without any direct evidence of fire or deliberate interment of the bodies, the suggestion that H. naledi might have been surprisingly sophisticated, given its small brain size remained firmly in the realm of speculation.

Subsequent work in the cave has materially strengthened that case. Berger and his colleagues report evidence for burials in two locations in Rising Star, the Dinaledi Chamber and the Hill Antechamber. H. naledi corpses were intentionally placed in pits that had been dug in the ground, and the bodies were then covered with dirt. In one case, the corpse was arranged in the pit in a fetal position—a common feature of early H. sapiens burials. In another H. naledi burial, a rock that the team describes as stone-tool-like was found next to the hand of one of the deceased. If it is indeed a stone tool or other manufactured artifact, it’s the only one that has been discovered in association with H. naledi to date.

After finding the burials, Berger and Hawks set their sights on searching Rising Star for more clues to the culture of H. naledi. And this time Berger wanted to explore the cave system himself. A large man, he had never been able to get into the parts of Rising Star where the H. naledi remains are found—he just couldn’t fit through the tightest points on the route into the fossil chambers. Berger hired a team of skinny scientists to do all the exploration and excavation that led to the initial research publications. Then, last summer, after losing 55 pounds (25 kilograms), Berger finally ventured into the heart of Rising Star. And that’s when he noticed soot on the ceiling and charcoal and bits of burned bone on the floor, which indicated that fire had been used in the cave. At the same time, team member Keneiloe Molopyane of the University of the Witwatersrand, who was excavating another part of the cave system known as the Dragon’s Back, found a hearth. “Almost every space within these burial chambers, adjacent chambers and even the hallways … has evidence of fire,” Berger says.

Berger also made another, arguably more astonishing discovery that day in Rising Star: designs carved in the cave walls. The engravings consist of isolated lines and geometric motifs, including crosses, squares, triangles, X’s, hash marks and scalariform, or ladderlike, shapes. The markings were deeply incised into dolomite rock in locations close to the burials in the Dinaledi Chamber and Hill Antechamber. Dolomite is a particularly hard rock that measures around 4.7 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness—“about halfway to a diamond,” Berger says. That means the engravers would have had to put considerable effort into making these marks. The engraved surfaces also appear to have been smoothed with hammerstones and polished with dirt or sand, according to the researchers. And some engraved areas gleam with a residue that may be the result of the rock being repeatedly touched.

If H. naledi, with its small brain, was burying its dead, using fire as a light source and creating engravings, then scientists may need to rethink the connection between brain size and behavior. We need to step back and try to understand “the social and community emotional dynamics that allow this kind of complex behavior without having this big, complex brain,” says team member Agustín Fuentes of Princeton University. Taking this perspective makes us think about human evolution in a new way, he adds, and reminds us that “we know a lot less than we thought we did.”

“It’s challenging our perceptions of what it means to be human, what it means to be intelligent enough to make art, what it means to communicate graphically,” says Genevieve von Petzinger, an authority on rock art, who was not involved in the new papers. Just 25 years earlier the conventional understanding was that Homo sapiens invented art in Europe 35,000 years ago. Over the past two decades researchers have uncovered evidence that our cousins the Neandertals and Denisovans made art, too. H. naledi had a much smaller brain than those hominins, though. Von Petzinger notes that the Rising Star findings are preliminary and that researchers have yet to carry out the detailed studies that will allow them to figure out “who was making what, where and when.” But, he adds, “I think as long as we approach this as being the start of a new and exciting conversation, then we’ve got nothing to lose by being open-minded about it.”

Some experts who were not involved in the new research think Berger and his colleagues are getting ahead of themselves. “I’m not convinced that the team have demonstrated that this was deliberate burial, i.e. the excavation of a shallow grave, deposit of a corpse in it and subsequent covering of that corpse with the sediment excavated,” says archaeologist Paul Pettitt of Durham University in England. A complete excavation of the remains would probably resolve the matter, he says, but the researchers’ “sensible” decision to leave some deposits intact for now means that “their data are partly investigated and, however impressive they are, sadly do not present a clear and unambiguous demonstration of deliberate burial.” Pettitt suggests that seasonal, low-energy movement of water in the cave system might have washed H. naledi’s remains into natural depressions in the ground.

Archaeologist Michael Petraglia of Griffith University in Australia thinks the researchers have made a good case for the burials, but he questions the claims that H. naledi was responsible for the engravings. One big problem is that scientists have yet to directly date the marks. The discovery team argues that there are no indications that any hominins other than H. naledi and modern cavers have entered the dark zone of Rising Star, where the fossil and archaeological materials have been found, and that the designs are therefore best attributed to H. naledi. Petraglia isn’t persuaded, however. “The evidence that Homo naledi made the rock engravings is weak. Though skeletal material and the engravings are in the same cave context, at present there is no way to directly associate them,” he says. The fire evidence is similarly problematic: the researchers have yet to publish dates for the material. “I have no reason to believe, at this stage, that Homo naledi controlled fire, and I await convincing scientific evidence to prove this is the case,” Petraglia says.

The team is working to obtain that evidence and more, including genetic material, which could reveal the relationships among the H. naledi individuals found at the site, for example. And the scientists are hoping to involve other researchers in their efforts as they think through how best to proceed with studying the wealth of material in the cave system. Some types of analysis depend on inherently destructive methods, such as excavation; others depend on less invasive ones, such as laser scanning. “You’ve now met a species that’s more complex than contemporary large-brained hominins, and this was its space,” Berger says of Rising Star. “What do we do with it? Destroy it? Respect it? I think we should discuss this as a community.”

[ad_2]