[ad_1]

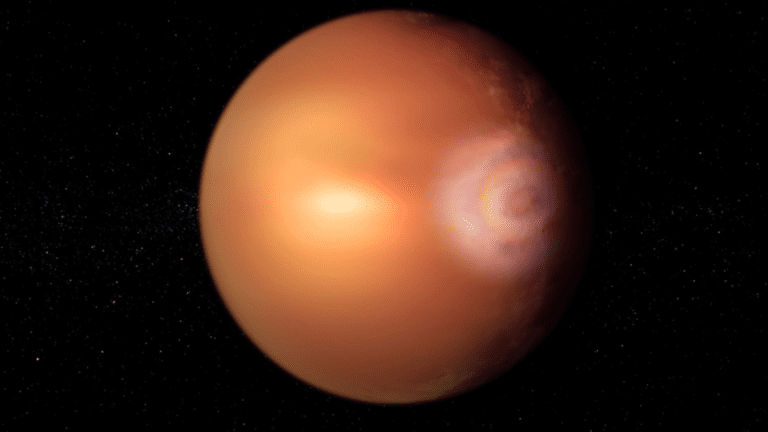

There are many words that could be used to describe WASP-76b — hellish, scorching, turbulent, chaotic, and even violent. This is a planet outside the solar system that sits so close to its star it gets hot enough to vaporize lead. So, as you can imagine, until now, “glorious” wasn’t one of those words.

This more positive descriptor was added to the list quite recently, as astronomers have detected hints of something called “glory” in the atmosphere of the ultra-hot Jupiter exoplanet. The glory effect, hinted at in data from the European Space Agency’s exoplanet-hunting mission Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite (CHEOPS), is a rainbow-like arrangement of colorful, concentric rings of light that occur only under peculiar conditions.

This effect is often seen over our own planet, as well as in the atmosphere of our violent neighbor Venus, but this is the first time scientists have seen it happening outside our cosmic neighborhood; WASP-76b is located 637 light-years away from us.

If the effect is confirmed to be happening over WASP-76b, it could reveal a great deal about this strange and extreme exoplanet — a world unlike anything seen in our stellar domain.

Related: Ultra-hot exoplanet has an atmosphere of vaporized rock

“There’s a reason no glory has been seen before outside our Solar System – it requires very peculiar conditions,” Olivier Demangeon, team leader and an astronomer at the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences in Portugal, said in a statement. “First, you need atmospheric particles that are close-to-perfectly spherical, completely uniform and stable enough to be observed over a long time. The planet’s nearby star needs to shine directly at it, with the observer — here CHEOPS — at just the right orientation.”

There’s more to WASP-76b than molten iron rain

Discovered in 2013, WASP-76b is located just 30 million miles from its parent yellow star, which is around 1.5 times the mass and 1.75 times the width of the sun. This distance is just a 12th of the distance between the sun and Mercury, which is the closest planet to our star.

As a result, the planet, which is around 1.8 times the size of Jupiter despite only possessing 92% of the gas giant’s mass, whips around its star in just 1.8 Earth days. This proximity also causes one side of WASP-76b, the “dayside,” to be tidally locked to face its star, WASP-76. The other side of the planet, the “night side,” perpetually faces out into space.

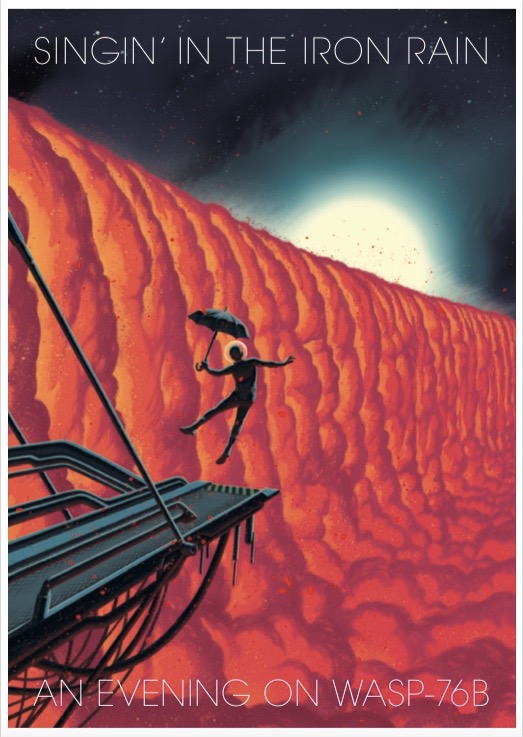

As the dayside of WASP-76b is blasted by radiation from its host star, temperatures there soar in excess of 4,350 degrees Fahrenheit (2,400 degrees Celsius). That’s hot enough to vaporize iron. Strong and fast winds on WASP-76b then carry this iron vapor to the cooler, night side of the planet, where it condenses into droplets and falls as iron rain.

The hint of the glory effect over this blistering exoplanet is a remarkable achievement for CHEOPS, which launched in December 2019. It exemplifies the mission’s capability to detect subtle, never-seen-before phenomena in faraway worlds.

CHEOPS observed WASP-76b nearly two dozen times over the course of three years as scientists attempted to understand a strange light-asymmetry found in the planet’s outer limbs, seen when it crosses, or “transits,” the face of its parent star.

These observations revealed an increase in the light coming from WASP-76b’s eastern “terminator line,” the divide where the exoplanet’s nightside becomes its dayside. The team concluded that this sharp change in light output is caused by a strong, localized, and directionally dependent reflection. They call it the glory effect.

“What’s important to keep in mind is the incredible scale of what we’re witnessing,” Matthew Standing, an ESA Research Fellow studying exoplanets, said in the statement. “WASP-76b is several hundred light-years away — an intensely hot gas giant planet where it likely rains molten iron.

“Despite the chaos, it looks like we’ve detected the potential signs of a glory. It’s an incredibly faint signal.”

What does glory mean for WASP-76b?

The glory effect may have a rainbow-like appearance and colorful striped pattern, but it’s actually quite distinct from a literal rainbow.

Rainbows are created when light from the sun passes from a medium with one density to another medium with a different density, usually from air to water. This causes the path of light to bend, or “refract,” and different wavelengths are refracted to different degrees. Thus, white light from the sun is split into its consistent colors, giving rise to the familiar ordered and colorful arc of a rainbow.

On the other hand, the glory effect happens when light passes through a narrow gap. On Earth, this gap could be the space between water droplets in clouds, for instance. This causes a different form of refraction, called “diffraction,” which happens when light passes an obstacle or through an aperture.

As the light waves split and then reunite, where peaks meet troughs, there is destructive interference. But, where a peak meets a peak, there is constructive interference. This results in dark and light bands, respectively, and concentric rings of color.

So what does glory mean for WASP-76b?

The presence of this phenomenon in the atmosphere of the ultra-hot Jupiter indicates the presence of clouds composed of perfectly spherical water droplets that have either lasted for at least the three years or clouds that are constantly being replenished.

If the clouds are persistent, this indicates that the temperature of WASP-76b’s atmosphere, while intimidating, must be stable over time. This is a fascinating insight hinting at stability around what had long been considered an endlessly turbulent world.

The results also indicate that exoplanet experts could investigate distant worlds for similar light phenomena, including starlight reflecting off liquid lakes and oceans. This is something that could be vital in humanity’s ongoing search for life beyond the solar system.

“Further proof is needed to say conclusively that this intriguing ‘extra light’ is a rare glory,” Project Scientist for ESA’s upcoming Ariel mission, Theresa Lüftinger, said. “Follow-up observations from the NIRSPEC instrument onboard the James Webb Space Telescope could do just the job. Or ESA’s upcoming Ariel mission could prove its presence. We could even find more gloriously revealing colors shining from other exoplanets.”

For Demangeon, this potential observation validates this continued interest in investigating the hellish world of Wasp-76b.

“I was involved in the first detection of asymmetrical light coming from this weird planet—and ever since, I have been so curious about the cause,” the ESA scientist concluded. “It has taken some time to get here, with moments when I asked myself, ‘Why are you insisting on this? It might be better to do something else with your time.’

“But when this feature appeared out of the data, it was such a special feeling – a particular satisfaction that doesn’t happen every day.”

The team’s research is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

[ad_2]