With her knack for fixing household appliances in early childhood, Yvonne Y. Clark, known as Y.Y. throughout her career, was practically born an engineer. And fortunately, she had a family that nurtured her atypical interest—even when the segregated South made pursuing it almost impossible.

With a librarian mother and a physician father, Y.Y. was brought up in a supportive, educated and prosperous Black enclave of Louisville, Ky. Her parents nurtured her knack for engineering. She got her start as a young child when she repaired the family toaster. An early introduction to a Black pilot group inspired her to fly planes, and she applied to the University of Louisville, where she hoped to study engineering and eventually aeronautics—until she learned her race disqualified her.

This podcast is distributed by PRX and published in partnership with Scientific American.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Episode 1: If You Want It, You Will: Growing Up in Segregated Louisville

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: She was known in her family for being able to fix things. She grabbed the toaster and took it up to her room, and decided she was going to take it apart and figure out why it wasn’t working. And…

KATIE HAFNER: Oh my goodness… Who does that?

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: I know. She was young. She was maybe nine.

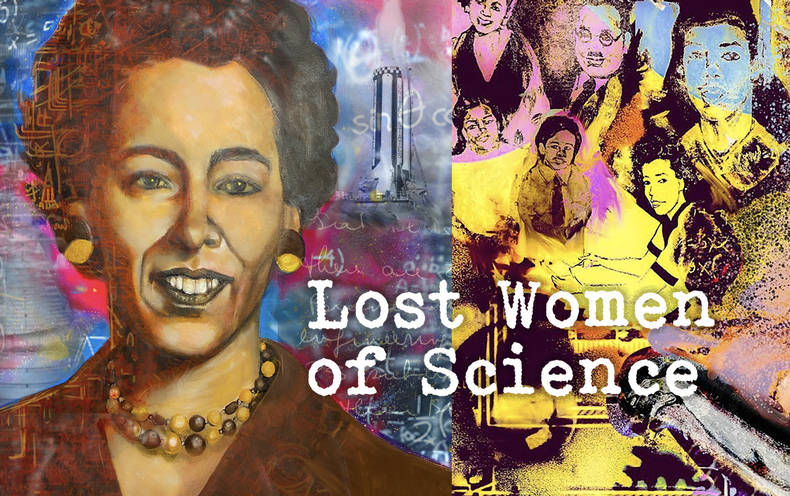

KATIE HAFNER: I’m Katie Hafner. And this is Lost Women of Science. We’re calling this season “The First Lady of Engineering.” It’s about Yvonne Young Clark, who we’ll come to know by her nickname, YY.

From day one at Lost Women of Science, we set out to include female scientists in all their diversity. Anyone who has seen Hidden Figures or read the book knows that female scientists are a wonderfully diverse group—and always were…

Our producer Sophie McNulty found YY in a book titled Black Women Scientists in the United States, by Wini Warren. The chapter was about a mechanical engineer named Yvonne Young Clark, whose passion for tinkering led to a brilliant career in both industry and academia. Around that time we’d gotten interested in this idea of “chains of knowledge” and the importance—to this day—of female mentors for young women in science. And we thought dedicating a full season to someone who made teaching and mentoring a huge part of her mission might be fascinating. And we were right.

CHARLES FLACK: She was the first African American female faculty member, as well as the first African American engineering female department head at Tennessee State. So when she was around, it was like, you know, you walk different, you acted different.

PEGGY BAKER: You know, you’re walking down the hall, “Baker!” I’m like, “yes, ma’am.”

KATIE HAFNER: YY was beloved in her circles and well beyond. In 1964, Ebony Magazine ran a big profile of her. Among students and fellow engineers, she was a celebrity, a legend, even.

When I first looked up YY, I found a slew of firsts: She was the first woman to get a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Howard University, the first African American woman engineer hired at RCA-Victor, the first African American member of the Society of Women Engineers, the first woman to earn a master’s degree in engineering management from Vanderbilt University…

I learned that at NASA, she worked on engines for the Saturn Five rocket, which launched the first astronauts to the moon. She helped design the sealed boxes that transported moon rocks back to Earth.

And most of this work she did over summer breaks; because during the academic year YY was teaching. She taught mechanical engineering for 55 years at Tennessee State, a historically Black university in Nashville. She inspired generations of young Black engineers, both men and women.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: So I fully expected, it would be someone that I would have some familiarity with. I mean, I’ve got a fairly good knowledge of African American history and I…

KATIE HAFNER: That’s Carol Sutton Lewis—the same person you heard at the very beginning. Carol and I have been tracking down YY’s story together, and having weekly phone calls to touch base.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: …and what’s been really interesting is as we have delved into her story as a, as a mechanical engineer and as a Black woman in the south, a lot of what we find comes back to her family.

KATIE HAFNER: To tell YY’s story, which in many ways is a family story, Carol is joining me as cohost this season. She has a background as a lawyer, and she hosts her own podcast called Ground Control Parenting, which is a series of conversations about parenting Black and Brown children.

Carol did the bulk of the reporting about YY Clark.

So Carol, YY’s story is one of multitudes. Where did you start?

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: So the first thing I did was I went to Seattle to meet YY’s daughter, Carol Lawson.

Carol came to the Airbnb where I was staying. She pulled up in her car with stacks of material she had on her mom.

Carol laid out all the books and papers on a table, and once we sat down, we dove into the photos.

CAROL LAWSON: That’s Mom.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Oh. Wow. At Redstone Arsenal in 1964.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: It’s a black and white shot of YY standing next to a rocket with “U.S. Army” stenciled on the side—and she is beaming. She’s wearing a cute sleeveless dress and heels.

CAROL LAWSON: There’s, there’s her and Hortense.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: This one’s a baby picture—little Yvonne, on her mother’s lap.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: And look at the pearls. She’s holding her mother’s pearls.

KATIE HAFNER: YY was born Georgianna Yvonne Young on April 13, 1929 in Houston, Texas. She was named after two of her great aunts, Georgia and Anna, but she went by her middle name, Yvonne.

Right from the start, Yvonne showed an interest in all things mechanical.

ERECTOR CLIP 1: Erector: the all steel construction set for beginners or young builders or junior engineers.

KATIE HAFNER: YY loved her Lincoln Logs and her Erector Set…toys that were—at the time—exclusively marketed to boys.

ERECTOR CLIP 2: Erector has exciting appeal for all boys.

KATIE HAFNER: YY’s early engineering projects weren’t limited to her toys. In one of our weekly calls, Carol told me about one moment that might have been the pivotal one for YY’s career trajectory…

It’s time to explain what happened with that toaster…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: The family toaster stopped working, the toast was burning on one side and not heating up on the other, and her father said to the housekeeper, “Well, we’ll get a new one.” And YY grabbed the toaster and took it up to her room and decided she was going to take it apart and figure out why it wasn’t working.

And so she fixed it and she didn’t tell anyone. She snuck it back down into the kitchen.

The next morning YY woke up to the smell of toast. And she ran downstairs just in time to witness the housekeeper saying to YY’s father, “Wow. You got a new toaster really quickly,” to which YY’s father responded, “I didn’t buy a new toaster,” and he determined that YY had fixed it.

KATIE HAFNER: After a quick fire safety talk, he told her how impressed he was.

KATIE HAFNER: Doesn’t it speak volumes about her father too?

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Oh, absolutely. The family’s perspective was if you want to do this, let’s figure out how you do this and we’ll support you doing it.

KATIE HAFNER: YY’s family would make all the difference when it came to nurturing her interests, and eventually, helping her build a career.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Her mother, Hortense Houston Young, grew up in Texas…

CAROL LAWSON: She went to Fisk…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: That’s Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville…

CAROL LAWSON: …majored in English…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: …and then got a second bachelor’s degree in library science from the University of Illinois…

CAROL LAWSON: And she also married my grandfather, Dr C. Milton Young.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s father, Dr. Coleman Milton Young, studied medicine at Fisk, and the family eventually moved to Louisville, Kentucky.

TOM OWEN: They lived in the 800 block, 818, South 6th Street. So the traditional Black business district, would’ve been about five blocks to the north,

KATIE HAFNER: Tom Owen is an archivist at the University of Louisville. Carol and I sat down to talk to him about his true passion: the city of Louisville itself.

TOM OWEN: I’m 82 years old. I still do walking tours, bicycle tours, that’s about it. A Louisville native.

KATIE HAFNER: Tom told us he often bikes past YY’s old block. It’s auto shops and massage parlors now, but back in the thirties, it was a row of brick, shotgun-style houses, where upper middle class Black families lived.

TOM OWEN: Yvonne was raised in a family that would have been among the most comfortable African American families here in Louisville.

KATIE HAFNER: The Youngs hosted derby parties and political fundraisers. YY’s father, the doctor…

TOM OWEN: He was on the staff of the private, uh, African American hospital called Red Cross hospital. And he was chief of staff for a, a season. He also was the, uh, physician at Louisville Municipal, which was a racially separate undergraduate college of the University of Louisville.

KATIE HAFNER: Hortense worked at the University too, as a librarian. She also wrote a newspaper column for the Louisville Defender. It was called “Tense Topics,” both because her nickname was Tense, and because she wrote about the issues that riled her up most: segregation, housing discrimination, and civil rights.

1930s Louisville gave her plenty to work with: At the time, there was only one department store in Louisville where Black customers could try on clothes. YY’s school, like all schools, was segregated, and Black residents lived with the constant threat of racist violence, including the threat of lynchings.

TOM OWEN: It’s not a pretty picture.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: This was the world YY—and her younger brother, Milton—were brought up in. A segregated city, in the segregated South, at the start of the Great Depression. YY would need more than a knack for machinery to make it as an engineer.

Her daughter, Carol, points to two sources of strength YY drew from: the first was that, from a very early age…

CAROL LAWSON: She was a congenital stutterer.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: When YY started school, she stuttered. And as you might imagine, the reactions from other children were not kind. It reached a point where YY practically stopped talking in her classes.

CAROL LAWSON: That was an early introduction to, not discrimination, but ill feelings from other humans for no reason.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: But YY got something out of all of this—something Carol calls her “rhino-skin.”

CAROL LAWSON: When you’re subjected to that at an early age, you start to learn a lot about humans and recognizing, that’s your problem. I’m not wrong. That’s your problem. I got to slow down what I have to say so I can be clear. But I am right. Just because I stutter doesn’t mean I’m wrong.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: The second source of YY’s strength takes a little more explaining. When Carol started showing me the books she’d brought, I quickly discovered…

CAROL LAWSON: Most of them are about her family.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s family has a fascinating history—and it’s recorded.

CAROL LAWSON: This is The Precious Memories of a Black Socialite: A Narrative of the Life and Times of Constance Houston Thompson. Who’s she? She’s my mom’s mother’s sister.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Carol had all these books about her mother’s relatives, and they went back multiple generations.

CAROL LAWSON: And so this one is the movement of rural African-Americans to Houston, speaking specifically about the Houston family.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s family, on her mother’s side, were Houstons. And the reason they had the last name Houston…

CAROL LAWSON: So the book is about the legacy of the slaves of Sam Houston.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: General Sam Houston, founding father of Texas, reason why the city of Houston is called Houston, owned slaves.

And one of the men he enslaved was…

CAROL LAWSON: Joshua Houston

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s great grandfather.

SKIP GATES: Our ancestors were, by law, they were owned by other people, right? They were property, they were commodities. They were chattel.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: That’s Henry Louis Gates, Jr., or as he’s called by many, Skip Gates.

SKIP GATES: In reality, they were human beings fighting for their humanity, just as Joshua Houston Sr. was.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Skip Gates is a historian, professor, and literary critic who serves as Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. You might know him as the host of the PBS series Finding Your Roots.

Like me, he was interested to discover YY’s lineage and to learn about Joshua Houston.

SKIP GATES: You know, he’s been written about…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s great grandfather, Joshua Houston, was born into slavery in 1822, in Alabama. And one of the first things I learned about him was that he could read and write. This was at a time when in many Southern states, that was illegal.

SKIP GATES: In Joshua Houston’s case, he participated in Bible study while owned by his first master and mistress, Temple and Nancy Lee.

When Temple Lee died, he left Joshua to his daughter, Margaret, and as you know, Margaret would marry Sam Houston.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Their marriage is how Joshua Houston wound up in Texas with the last name Houston.

His education meant that following the Civil War and emancipation, Joshua was in a better position to pursue life as a free man. He bought property, and opened his own blacksmith’s shop.

This was during the time known as Reconstruction, in the years after the war.

SKIP GATES: the hallmarks of reconstruction were the ratification of what we now call the Reconstruction Constitutional Amendments: the 13th amendment…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: …which ended slavery…

SKIP GATES: The 14th amendment…

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: …which established birthright citizenship, and gave all US citizens equal protection under the law.

SKIP GATES: And then finally the 15th amendment, which gave all Black men the right to vote.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: A right that was unprecedented, and eagerly exercised.

SKIP GATES: The first freedom summer, as I put it, was the summer of 1867, when all those Black men formerly enslaved and free got the right to vote. They registered to vote in that first freedom summer, 80%. Think about that.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: And some of them ran for office—including Joshua Houston.

SKIP GATES: He was a city alderman in Huntsville, Texas in 1867 and in 1870, and he won election as a county commissioner in 1878 and in 1882.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Joshua went on to have eight children, and he made sure they also had access to education and opportunities. One of his sons went to Howard University and ultimately founded a school—the first African American school in Texas to go to the 12th grade.

The Houston children were politically engaged, college-educated, and they owned property.

SKIP GATES: And so I did some research and about 20% of the Black community was able to own property by 1900.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Which means, of course, 80% didn’t. The Houstons were part of a small, privileged class of Black people that flourished during Reconstruction.

SKIP GATES: So we’ve always had these class divisions within the African American community.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: The Houston family history illuminates a part of Black history that often gets lost—and that is the history of Black prosperity.

Still, their relative privilege didn’t end the reality of racism, or the potential for violence. Especially because in the wake of the expansion of rights during Reconstruction, there was a brutal backlash.

SKIP GATES: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Texas has a register of, of murders listing over a thousand in the year between 1865 and 1866.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Black people faced a constant terrorist threat.

So vigilante violence, in other words, was a continuous part of Reconstruction.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS:And soon, the legislative rollback began. Laws were put into place to reestablish a system of economic and political disenfranchisement for Black Americans. This was the so-called “Redemption” of the Southern states.

SKIP GATES: And it has that funny name because these racists saying, they were redeeming the purity of the South, because of the evils of what they called Negro rule.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Reconstruction and its early promise of expanding rights collapsed in 1877, when federal troops pulled out of the South.

SKIP GATES: And it was those federal troops that were guaranteeing the right of Black men to vote in the south.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Without that guarantee, it became all too easy for the so-called Redeemers to strictly enforce segregation. For Black Americans like YY’s family, this meant forging their own world.

SKIP GATES: if you lifted up the curtain, the color curtain, Black people under segregation, were not saying woe is me and not, you know, begging for admission into the white world.

They formed a rich and various and diverse and nurturing Black world that had deep roots and sustained us.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s relatives were exemplars of this legacy. They gathered in Black fraternities and sororities, at cotillions, bridge parties. They created strong, resilient communities and found ways to thrive. Her family included journalists, doctors, cooks, teachers.

CAROL LAWSON: And she knew them. And they weren’t mythical people on the wall that I’ve seen, you know, and grandma told me a story, you know, she knew those people.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: This was the second source of YY’s strength.

CAROL LAWSON: And, and it helps you understand why Yvonne was the way Yvonne was, or YY was the way she was. They were all about promoting, protecting, and uplifting Black folk. 110%.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Coming up, YY’s family needs to put up a fight…

CAROL LAWSON: Don’t do anything wrong to Black folks. Cause we’re gonna come get you.

YY: I am Yvonne Y. Clark. 78. Today’s date is October the 26th, 2007. Nashville, Tennessee. And I’m being interviewed by my daughter.

KATIE HAFNER: That’s YY you’re hearing.

This tape is from a StoryCorps interview she recorded with her daughter, Carol Lawson.

YY died in 2019, a few months shy of 90 years old.

CAROL LAWSON: So Yvonne… Mom.

YY: Thank you.

CAROL LAWSON: Tell me, why did you want to become an engineer?

YY: I wanted to ferry airplanes between the United States and England.

KATIE HAFNER: This was the early 1940s, and the US had just entered World War II. The Youngs opened up their Louisville home to the Black military personnel based in Kentucky. Here’s YY describing that.

YY: Mom and dad had parties and the Godman Field pilots would come by the house. That was the Black pilot group. You’d hear them talk about their flyings around the United States and the world, and it made me want to fly.

KATIE HAFNER: I just need to say, Carol, that—I love her voice so much.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Yeah, absolutely.

KATIE HAFNER: Anyway, so she, she decided to become a pilot. And the Godman pilots she met that night, they were all men. But she didn’t—one thing that is striking me about the whole YY story to date is that the fact that she was a woman doesn’t seem to have figured into that. So anyway, but at the time, it seemed like a future in aviation might be possible for a young woman, too…

ARCHIVAL TAPE: This is Texas, cradle of our Army’s airforce.

KATIE HAFNER: With so many male pilots overseas, the US Army Air Force began to recruit women.

ARCHIVAL TAPE: And out of those buses are stepping girls, girls who give a new angle to an airforce story. They’re WASPS.

KATIE HAFNER: These “girls” were known as Women Air Force Service Pilots, or WASPs.

ARCHIVAL TAPE: Nobody should ever tell a WASP that flying’s not a woman’s job. They wouldn’t believe it.

KATIE HAFNER: But at the time that YY got interested in flying, there were no Black WASPs. Mildred Hemmons Carter, a Black pilot who trained at Tuskegee, applied, and qualified, but was rejected on the basis of race.

That didn’t stop YY. She had made up her mind—she was going to use her mechanical skills towards aviation. And since all the pilots she talked to had studied engineering, she decided to do the same.

MILTON CLARK: Literally the next day, she went down to Central High School and looked up what their engineering courses were so that she could sign up for them for the next semester.

KATIE HAFNER: That’s YY’s son, Milton Clark.

MILTON CLARK: She had bought her T-square and she bought her protractor and everything that she needed to take the course. And when she went to the classroom, the instructor wouldn’t let her in… because she was a female.

KATIE HAFNER: YY called this her first experience of “pure sexism.” Why “pure?” Because, in her words, “it made no logical sense.” That’s something to note about YY; for her, discrimination wasn’t just morally wrong, it was wrong because it defied reason. It’s impossible to disentangle YY’s ethics, her spirit, and her world view from her adherence to logic and reason.

Her rejection from the school’s mechanical drawing course was also completely different from how she was accustomed to being treated at home. Her parents nurtured her ambitions, and when they said no, they had good reason.

And it was her parents who, through their tight-knit, talented, diverse community, offered YY a path to the sky.

Literally.

YY: Mom had a friend. He had an airplane,

KATIE HAFNER: YY’s mother got her friend to take them on a flight. Hortense sat in the back, so her daughter could sit in the cockpit next to the pilot.

YY: And, uh, he let me take over the controls once he took off and mom was on the passenger seat in the back, it was nice.

CAROL LAWSON: So that’s kind of where it all began.

YY: Mmmhmm.

CAROL LAWSON: Okay.

KATIE HAFNER: Back at school, YY found a practical workaround after being rejected from the mechanical drawing class: She signed up to take the course over the summer, with a different teacher.

Another semester, she took an aeronautics class, where she learned about the mechanics of airplanes.

YY: That was, that was cool. We would make planes. You would go out on the fire escape, roll your propeller, and then aim it at the football field and watch it fly.

KATIE HAFNER: YY zoomed through high school. After only two years, she graduated in the top 25% of her class at Central High School in Louisville. She was only 16.

Her parents thought that was too young to start college, so they sent her up north to stay with a family friend, and take a few additional courses…

YY: So I went to Boston for two years and attended Girls Latin, where I took French and Latin, et cetera.

KATIE HAFNER: Two years later, when she turned 18, it was time to apply to college.

YY: I applied to University of Louisville, down the street from me, uh, University of Illinois at Urbana, and Howard University in Washington, DC.

KATIE HAFNER: According to Milton, her son, YY was accepted at all three schools. But after two years in Boston, her preference was to stay close to home.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: So YY picked the University of Louisville. And as Milton tells it, in 1947, she went to a scheduled orientation with her mother, Hortense, acceptance letter in hand. YY’s daughter Carol tells us that YY was all set to confirm attendance…

CAROL LAWSON: Until they found out she was Black. And then they said, oh no, you can’t come.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: As in many other times, in YY’s life, everything was fine until they saw her. As YY herself told her daughter Carol,

YY: I couldn’t get in

CAROL LAWSON: Why?

YY: A Black down south.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: The University of Louisville was a segregated school.

TOM OWEN: The major obstacle was called the Day Law.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: That’s Tom Owen again.

TOM OWEN: And that had essentially been interpreted as a prohibition against biracial education in both public and private institutions.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Even if the University of Louisville had wanted to enroll YY, at that time in Kentucky, because of the Day Law, it was actually illegal for them to do so.

KATIE HAFNER: YY would have been expected to attend the segregated Black undergraduate college where both her parents worked, Louisville Municipal. But Municipal didn’t offer the classes that YY needed.

TOM OWEN: They would have some technical courses, but no, to my knowledge, they did not have a program in engineering at all.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Separate but equal was a fiction–as much in Kentucky higher education as anywhere else.

And the NAACP was constantly on the lookout for cases that would prove it…

TOM OWEN: Beginning in the 1930s, it was clear that the NAACP was pushing to get admission to graduate education in Kentucky.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: In 1941, the NAACP had taken on the case of an aspiring engineering student from Louisville named Charles Lamont Eubanks. The state’s segregated Black college had no engineering program, so Eubanks applied to the local all-white public university, and was rejected. In the end, the case was dismissed. Eubanks, or any Black high school graduate in Kentucky who wanted to study engineering, would have to look out of state.

KATIE HAFNER: Pretty much everything was set up to encourage YY to either give up on engineering, or go to school somewhere else. In fact, in Kentucky…

TOM OWEN: There was a fund to pay African Americans to go to graduate school out of state. It didn’t pay for expenses or living expenses to leave the state and the fund was frequently depleted.

KATIE HAFNER: Not only was the fund insufficient, graduate students were given priority. YY was applying as an undergraduate, so she would have found it difficult to qualify.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: But YY had gotten admitted—she had the letter. YY’s parents were not going to take this lying down. Remember, this is Hortense we’re talking about—NAACP member, journalist…So YY’s parents…

CAROL LAWSON: Being the educated folks that know what our rights are, said, you know what? We’ll take you to court. And then we’ll decide if she can come.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Hortense threatened to take legal action. She spent several days negotiating directly with the University of Louisville. If her daughter’s acceptance letter wasn’t going to get her admission, Hortense was going to make sure it got her something.

YVONNE CLARK: I asked mom, well, we live right there in Louisville. Why can’t we get room and board? Mom said, leave it alone, honey, leave it alone. I said, okay, mom, you’re in charge.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Eventually, they worked out a deal: Louisville would cover YY’s tuition at a school that admitted Black students, and the family would agree not to sue the university.

YVONNE CLARK: And University of Louisville paid my tuition at Howard University.

KATIE HAFNER: We wondered if the University of Louisville had any records from 1947, when YY started school. So we asked Tom to look. He did a lot of digging. Three days straight of combing through city directories, newspaper clippings, and the university’s own archives…And he found a file.

TOM OWEN: And guess what it was titled? Negro Admissions. I got those three goddamn files out. They start in 1948, not 1947, and she’s not in there.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: But I just couldn’t leave it at that. I asked Tom, “Isn’t it possible that the University didn’t want this on the record at all? Couldn’t the negotiations have happened behind closed doors?”

TOM OWEN: Oh, I don’t have any trouble believing that it could have happened. I’m just, you know, my, my, my orientation is give me the paper, give me the document. And I wish, I wish, you know, if I could live so long, I’d keep on looking.

KATIE HAFNER: My question was why she applied there in the first place. I have no doubt that YY’s family knew that the University of Louisville was a segregated school. They worked at Municipal, the University’s all-Black undergraduate college.

TOM OWEN: That does not surprise me. Hortense seems, just looking at the clips, clips, clips, clips, seems intense to me, committed to me, pushing on the edges, challenging things. And so that does not surprise me.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: It certainly didn’t surprise me either. This well educated, civically minded Black family is dealing with a rule that says their whip smart daughter, who wanted to be an engineer, was being denied that opportunity solely because she was Black? When the Youngs saw an unjust rule, they refused to accept it. And they actively challenged it.

TOM OWEN: Hortense especially was just a civic activist in the fullest sense of the word.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY might well have applied to the University of Louisville fully knowing how unlikely it was that she would be able to attend. The NAACP was applying this strategy across the country intentionally exposing and challenging discrimination. This was a template for the civil rights movement.

It wouldn’t be until 1948, the year after YY applied to the University of Louisville, that the NAACP filed the case that would overturn segregated higher education in Kentucky.

TOM OWEN: And Lyman Johnson was the successful one.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Lyman Johnson was a social studies teacher and NAACP member in Louisville. He taught at YY’s school—the segregated Central High School. Unlike YY, he was applying for graduate study—a PhD. It was immediately evident that Kentucky State, a Black undergraduate college, would not provide him with the coursework that a white PhD student would receive at the University of Kentucky. He sued the University in 1948, and in 1949, he won.

KATIE HAFNER: This victory didn’t make much difference to YY, who was already at Howard by then, but it changed a few things for her family. In fact, soon after YY made her deal with the University of Louisville…

MILTON CLARK: My uncle, her brother, made application.

KATIE HAFNER: Milton told us that YY’s younger brother also applied to the University of Louisville.

MILTON CLARK: So it was kind of like, okay here come the Youngs again.

KATIE HAFNER: This time, the university knew who they were dealing with. Plus, the decision in the Lyman Johnson case had just come out the previous spring, which is how…

MILTON CLARK: It’s my uncle, her brother, who broke the color barrier. And my grandmother broke the color barrier at the law school.

KATIE HAFNER: That’s right. Hortense would later go to law school at the University of Louisville. In 1951, she was one of four Black students to enroll.

MILTON CLARK: And that’s the thing, you know, we talk about mom, but the family is really the dynamic that’s in play here.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: YY’s family didn’t create her passion, her talents. Those were her own. What her family did do, and what they would continue to do, was make her interests viable in a world that wasn’t fair.

MILTON CLARK: There was nothing out of bounds with her parents.

YY: They didn’t put obstacles in front of me. They said, if you want it, you will.

CAROL LAWSON: I think that’s something that we probably, even as a community now, don’t give enough credit to: just how much effort it can take to raise an Yvonne.

KATIE HAFNER: Next time on Lost Women of Science, YY leaves the nest.

This has been Lost Women of Science. Thanks to everyone who made this initiative happen, including our co-executive producer Amy Scharf, producer Ashraya Gupta, senior editor Nora Mathison, associate producer Sinduja Srinivasan, composer Elizabeth Younan, and the engineers at Studio D Podcast Production.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Thank you to Milton H. Clark, Sr. Much of this story comes from his book, Six Degrees of Freedom.

KATIE HAFNER: We’re grateful to Mike Fung, Cathie Bennett Warner, Dominique Guilford, Jeff DelViscio, Maria Klawe, Michelle Nijhuis, Susan Kare, Jeannie Stivers, Carol Lawson, and our interns, Hilda Gitchell and Hannah Carroll. Thanks also to Paula Goodwin, Nicole Searing and the rest of the legal team at Perkins Coie. Many thanks to Barnard College, a leader in empowering young women to pursue their passion in STEM.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: Thank you to Tennessee State University, the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, the University of Louisville, and the University of Alabama in Huntsville for helping us with our search.

And a special shout out to the Print Shop on Martha’s Vineyard…

KATIE HAFNER: …and my closet, where this podcast was recorded.

Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the John Templeton Foundation, which catalyzes conversations about living purposeful and meaningful lives.

This podcast is distributed by PRX and published in partnership with Scientific American.

You can learn more about our initiative at lostwomenofscience.org or follow us on Twitter and Instagram. Find us @lostwomenofsci. That’s lost women of S C I.

Thank you so much for listening.

CAROL SUTTON LEWIS: I’m Carol Sutton Lewis.

KATIE HAFNER: And I’m Katie Hafner.