[ad_1]

NASA’s newest Earth-observing satellite has made it off the chopping block all the way to orbit.

The nearly $1 billion PACE mission, which the Trump administration tried to cancel four separate times, launched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket early this morning (Feb. 8) from Florida’s Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

When it’s up and running, PACE will make key observations of Earth’s atmosphere and climate and allow scientists to assess the health of our oceans like never before.

“What I’m most excited about is that PACE is going to so profoundly advance our understanding about how our oceans work and how they are related to the broader Earth system,” Karen St. Germain, director of NASA’s Earth Science Division, said during a prelaunch briefing on Sunday (Feb. 4).

“PACE is going to show us the biology of the oceans at a scale that we’ve never been able to see before,” she added.

Related: Earth is getting hotter at a faster rate despite pledges of government action

A smooth, fast launch

The Falcon 9 lifted off from Cape Canaveral’s Space Launch Complex 40 today at 1:33 a.m. EST (0633 GMT), after several days of delay caused by bad weather.

About 7.5 minutes after launch, the rocket’s first stage came back for a vertical touchdown at Landing Zone 1, a SpaceX facility at the Cape. It was the fourth launch and landing for this particular booster, according to a SpaceX mission description.

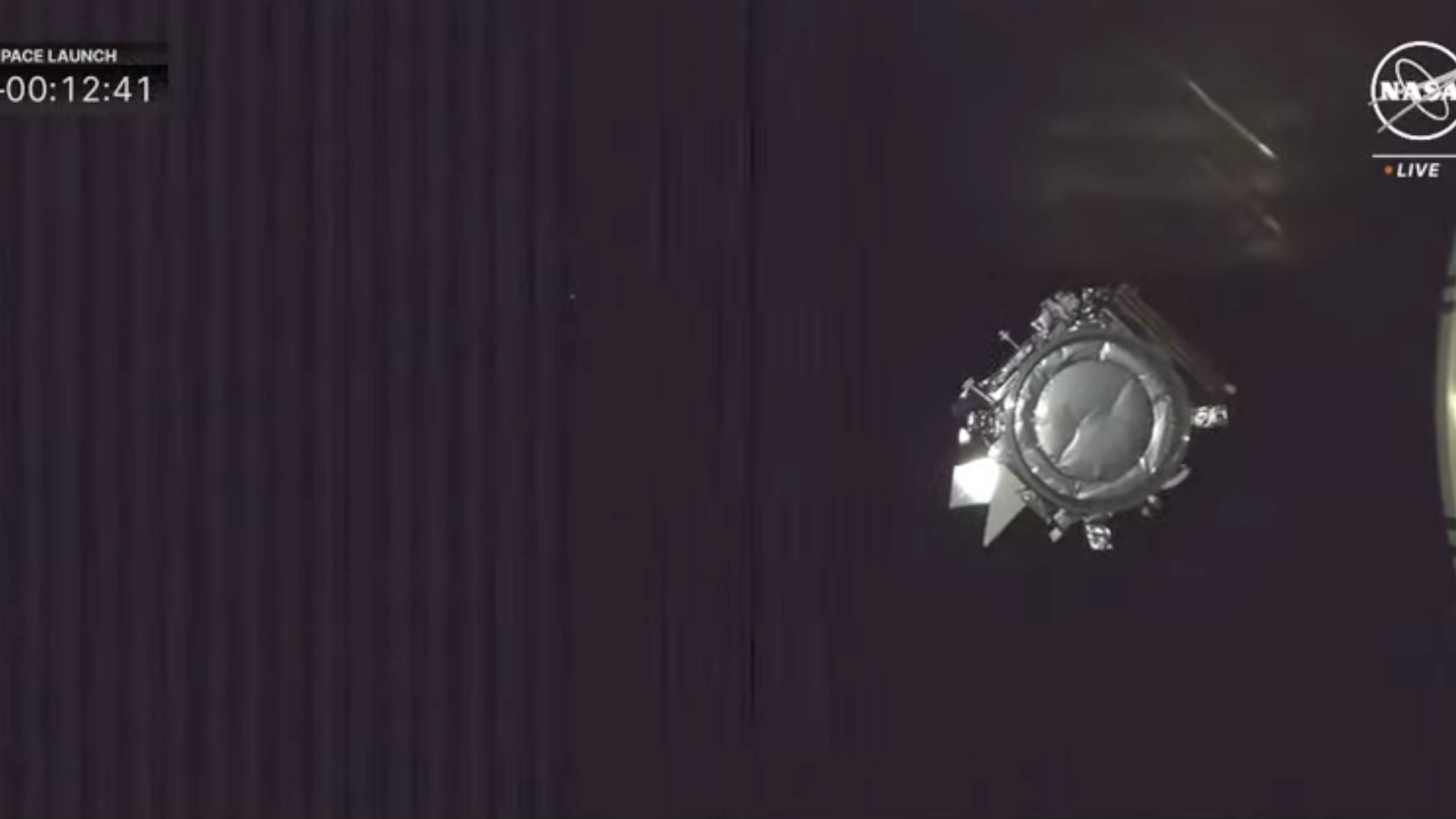

Just five minutes later, the Falcon 9’s upper stage deployed PACE (whose name is short for Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem) into a sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) about 420 miles (677 kilometers) above Earth — roughly 70% higher than the International Space Station flies.

In SSOs, which go over Earth’s poles, satellites see each patch of ground at the same solar time every day. Lighting conditions are therefore consistent, allowing spacecraft to monitor or detect changes on Earth’s surface more easily. For this reason, SSOs are popular destinations for weather and spy satellites.

PACE, by the way, is the first U.S. government mission to launch to a polar orbit from Florida since Nov. 30, 1960. On that day, a Thor Able Star rocket took off on such a trajectory but failed, raining debris down on Cuba, some of which apparently killed a cow. Rather than risk further incidents, the U.S. decided to conduct all of its subsequent polar launches from Vandenberg Air Force Base (now Vandenberg Space Force Base) in California — until now.

That said, PACE wasn’t the first mission of any type to launch to polar orbit from Florida’s Space Coast in six decades: SpaceX had completed 11 such commercial missions before sending PACE on its way.

The color of the ocean

PACE’s handlers will now work to get the 10.5-foot-long (3.2 meters) spacecraft and its various subsystems up to speed. After this checkout period, the satellite can begin its science work.

That work will be done by three instruments. One of them, a spectrometer called the Ocean Color Instrument (OCI), will map out the ocean’s many hues in great detail and an unprecedented range, from near-infrared wavelengths all way to the ultraviolet.

These colors are determined by the interaction of sunlight with particles in seawater, such as the chlorophyll produced by photosynthetic plankton, the base of the marine food web. So OCI will reveal quite a bit about the health and status of ocean ecosystems, according to PACE team members.

“PACE’s unprecedented spectral coverage will provide the first-ever global measurements designed to identify phytoplankton community composition,” NASA officials wrote in a PACE mission description. “This will significantly improve our ability to understand Earth’s changing marine ecosystems, manage natural resources such as fisheries and identify harmful algal blooms.”

The satellite’s other two instruments are polarimeters. They’ll measure how the oscillation of light in a plane, known as its polarization, is affected by passage through the ocean, clouds and aerosols (particles suspended in the atmosphere).

“Measuring polarization states of UV-to-shortwave light at various angles provides detailed information on the atmosphere and ocean, such as particle size and composition,” NASA officials wrote in the mission description.

So PACE’s contributions to Earth and climate science will be many and varied, agency officials stress.

“PACE is going to provide more information on oceans and atmosphere, including providing new ways to study how the ocean and atmosphere exchange carbon,” Kate Calvin, NASA’s chief scientist and senior climate advisor, said during Sunday’s briefing.

“In addition to the information PACE will provide that helps us understand long-term climate, PACE will also give us information about oceans and air quality that can help people today,” she added.

Related: Climate change: Causes and effects

A tough road to the launch pad

PACE powered through a fair bit of adversity on its way to the launch pad. For example, the administration of President Donald Trump tried to cancel the mission on four separate occasions, in its budget proposals for the fiscal years 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021. But Congress allocated the required funds each time, saving PACE from the chopping block.

The mission has dealt with delays and cost overruns as well. In 2014, NASA capped the mission’s total price tag at $805 million, with launch targeted for 2022. The cost has gone up, however, to $948 million.

But the wait and the money will all be worth it, according to St. Germain, who compared PACE favorably to NASA’s flagship James Webb Space Telescope.

“It’s going to teach us about the oceans in the same way that Webb is teaching us about the cosmos,” she said.

[ad_2]