[ad_1]

In recent nights there has been a brilliant light that has been calling attention to itself low in the eastern sky at around 7:30 p.m. local daylight time. It shines with a steady, silvery glow and a couple of hours later when it has climbed noticeably higher in the east-southeast part of the sky, it seems to command attention.

Of course, that would make some sense because you are looking at the object named after the king of the gods and also the king of the planets: Mighty Jupiter.

And this marks a rather auspicious week, for we will see Jupiter loom as large and as bright as it ever can get from our earthly vantage point, because it’s nearing perihelion: that point in its 12-year orbit that places it nearest to the sun.

Related: Jupiter is at its closest to Earth in 59 years, NASA says

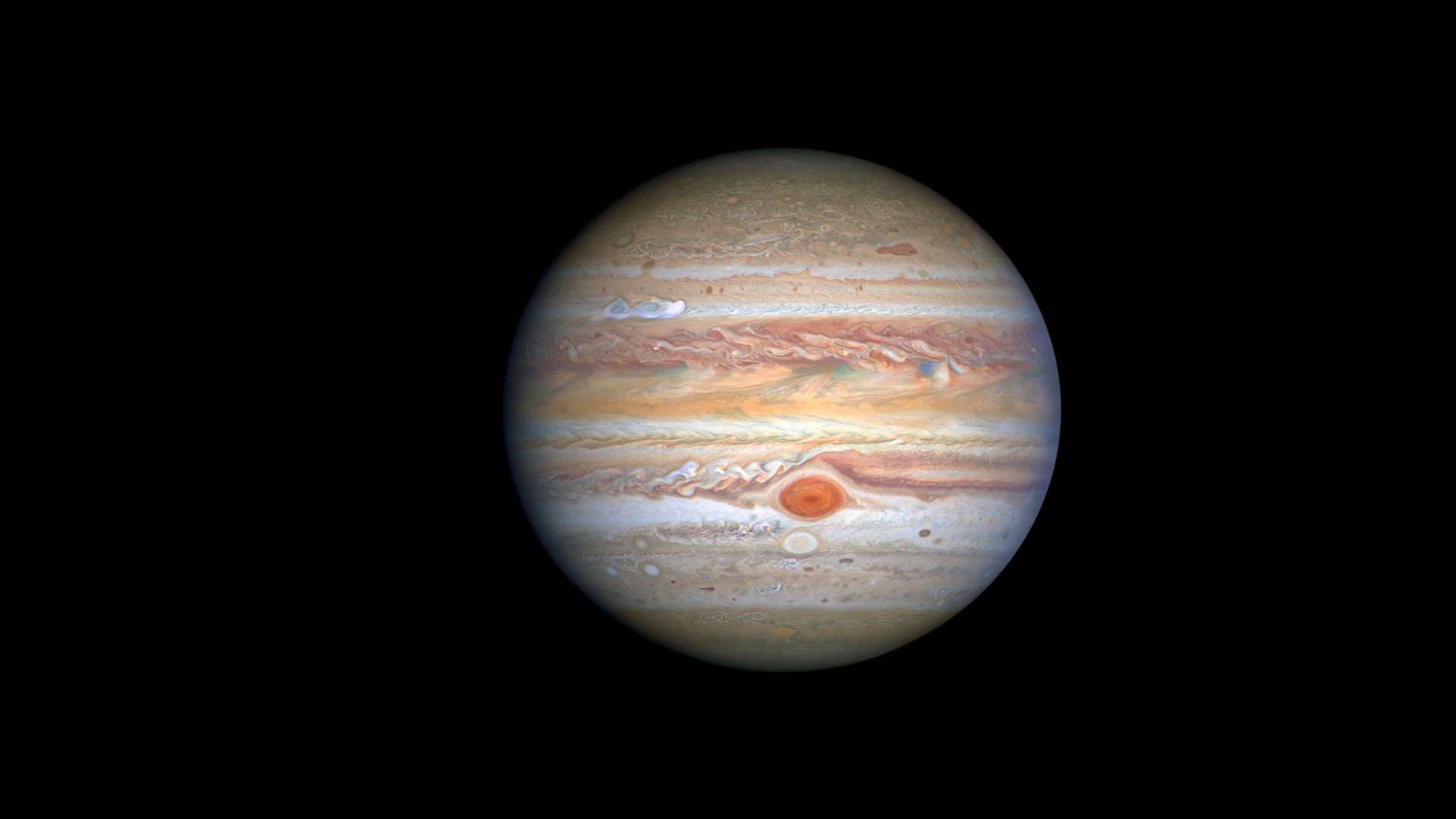

Jupiter now appears 11% larger and more than one and a half times brighter than it did back in April 2017, when it was near aphelion (that point in its orbit farthest from the sun). Even steadily-held 7-power binoculars will show Jupiter as a tiny disk. A small telescope will do much better, while in larger instruments, Jupiter resolves into a series of red, yellow, tan and brown shadings, as well as a wealth of other telescopic detail. Amateur astronomers have been imaging this big planet all summer long as it has been approaching the Earth. Opposition, when it will be in the sky all night long, from sunset to sunrise occurs on Monday (Sept. 26th).

At 10 p.m. Eastern Time on Sunday (Sept. 25), Jupiter will make its closest approach to the Earth since 1963. It will then be 367,413,405 miles (591,168,168 km) away. This may not seem exactly “close,” but Jupiter is so big and bright that it’s not only easily visible with the unaided eye, but through a small telescope magnifying only 36-power, it appears as big as the moon does to the unaided eye.

A giant among giants

Jupiter has a diameter almost eleven times that of the Earth at 88,846 miles (142,984 km) wide. It takes almost 12 years to complete one trip around the sun. But if Jupiter’s year is long, its day is short. The big planet rotates once in just under 10 hours. For a planet of this size, this rotational speed is amazing. A point on Jupiter’s equator moves at a speed of 22,000 m.p.h. as compared to 1,000 m.p.h. for a point on the Earth’s equator. That rapid rate of spinning gives Jupiter the look of a slightly flattened ball. It has a rocky core encased in a thick mantle of metallic hydrogen enveloped in a massive atmospheric cloak of multi-colored clouds of ammonium hydrosulphide.

Jupiter is a hulking giant of a planet, with a mass more than twice that of all the seven other planets lumped together. It has one of the most mysterious blemishes on the face of any planet: the Great Red Spot that comes and goes unpredictably, and is as wide as the Earth. There is also some evidence that Jupiter loses by radiation more heat energy than it acquires from the sun, and therefore it may be producing energy of its own — activity ordinarily more characteristic of a star than a planet.

Jupiter also possesses a faint ring system, although unlike Saturn‘s famous rings which are highly reflective because they are composed of ice, Jupiter’s rings are primarily made up of a myriad of tiny dust particles.

And like Earth, Jupiter has a magnetic field; a vast, doughnut-shaped belt of electrically charged particles that encircles the planet — a ring similar to the Van Allen belts of charged solar particles held prisoner by the Earth’s magnetic field.

The dance of the moons

Let’s not forget Jupiter’s four major moons, which were discovered 412-years ago by Galileo. They are a telescopic treasure. The four — Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — run a merry race with one another and orbit Jupiter so quickly (1.68 days for Io to 16.7 days for Callisto) that they change their appearance from hour to hour and from night to night, throwing their shadows on the planet, vanishing behind its giant disc, or plunging into its shadow.

On Sunday (Sept. 25) for instance, you’ll be able to see three moons on one side of Jupiter (Io, Europa and Callisto) with the fourth moon (Ganymede) all by itself on the other side. On Monday (Sept. 26), Ganymede will be joined by Europa and Io; now it’s Callisto that will be all by itself on Jupiter’s other side. Finally, on Tuesday (Sept. 27) you’ll see two moons on one side (Europa and Ganymede) and two (Io and Callisto) on the other.

In fact, at 12:08 a.m. EDT on Wednesday (Sept. 28) (9:08 p.m. Pacific Time on the 27th), Ganymede will appear to cross in front of Jupiter, called a transit. In addition to “The Big Four,” Jupiter has 76 other satellites. Many of these are exceptionally small and have been discovered courtesy of space probes which have passed close to Jupiter during the decades of the 1970’s, ’80’s and ’90’s.

Gyrating Jupiter?

When Jupiter appears high in the sky, it might appear to some to be moving in a circle or spiral. Over the years, I’ve received emails from people who claim to have seen Jupiter do just this: move back and forth.

So why does it appear to move? Likely those who have seen this strange movement have experienced the autokinetic effect. This is a phenomenon of human visual perception in which a stationary, small point of light in an otherwise dark or featureless environment appears to move. Many sightings of UFOs have also been attributed to the autokinetic effect’s action on stars or planets. Psychologists attribute the perception of movement where there is none to “small, involuntary movements of the eyeball.” The autokinetic effect can also be enhanced by the power of suggestion: If one person reports that a light is moving, others will be more likely to report the same thing.

Currently, Jupiter is shining in the constellation Pisces, a star pattern that consists chiefly of faint stars. Under a clear, dark sky with no moon nearby, Jupiter will appear to shine with little or no competition from other nearby stars. If a person constantly stares at Jupiter over a span of perhaps 15 to 30 seconds, it’s quite possible for the autokinetic effect to kick in and cause Jupiter to gyrate or perhaps describe a small circle.

This week, during the late evening hours, try staring at Jupiter and see if it’ll move for you.

If you want to catch a great view of Jupiter at oppostion, don’t miss our guides for the best binoculars and the best telescopes to spot Jupiter or other objects in the night sky. For capturing the best Jupiter pictures you can, check out our recommendations for the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Editor’s Note: If you snap a photo of Jupiter and would like to share it with Space.com’s readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to [email protected].

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).

[ad_2]