[ad_1]

This month saw the announcement of one of the most exciting findings about Venus in decades: the first direct evidence of an active volcano there. But rather than jubilation, the mood in the planetary science community is grim, as funding has been gutted for a key Venus mission that was poised to answer some of the biggest questions about the planet and its volcanic activity.

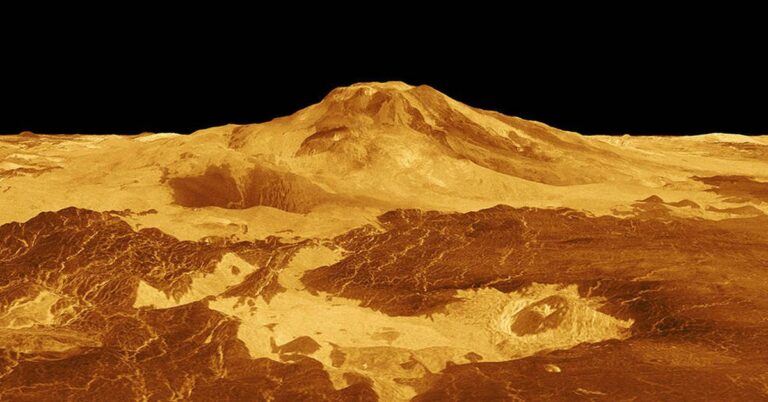

Venus is a hellish, inhospitable place with scorching surface temperatures and atmospheric pressure 100 times greater than Earth. Its surface is covered in volcanoes, and scientists have long suspected that these could still be active, but they have lacked firm proof of this until recently. Researchers combed through 30-year-old data from the Magellan mission and identified a volcanic vent that changed shape over the course of eight months with what appears to be lava inside and a possible lava flow running downhill.

But rather than jubilation, the mood in the planetary science community is grim

The short timeframe between the two images in the study, published in Science, suggests that volcanoes are likely erupting with some frequency. “When someone says that a planet is volcanically active that still could mean that the time between eruptions could be months, or years, or ten thousand years,” one of the paper’s authors, Robert Herrick, explained to The Verge. “This new discovery means that Venus is probably more or less Earth-like in terms of how often big shield volcanoes on Earth erupt.”

This finding is “mind-blowing,” Venus scientist Darby Dyar told The Verge, opening up possibilities to learn about Venus’ geology and atmosphere as well as whether the planet was once habitable.

But in the space science community, the excitement about this finding is being overshadowed by the “soft cancellation” of a key NASA Venus mission, which Dyar is also deputy principal investigator for and which had been set to launch in 2028.

The Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy (VERITAS) mission was one of three missions set to explore Venus in the next few years, kicking off NASA’s “decade of Venus” and seeing a return to the study of our planetary neighbor, which scientists have been calling for for years.

But at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference held recently in Houston, Texas, VERITAS principal investigator Sue Smrekar announced that the mission’s funding had been completely gutted, leaving the mission in a state of precarious limbo.

This finding is “mind-blowing,” Venus scientist Dyar said

This came as a surprise to many of the conference attendees, who were soon tweeting their support for the mission using the hashtag #SaveVERITAS. The Planetary Society also put out a statement describing the delay of the mission’s launch by at least three years as “uncalled-for” and calling on NASA to commit to launching by 2029.

NASA has cited problems with another mission, Psyche, as the reason for delaying VERITAS by at least three years. Both Psyche and VERITAS are managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the NASA / Caltech research center that is responsible for building robotic spacecraft such as the Mars rovers. JPL had problems meeting its requirements for the Psyche mission, which aims to visit a metal asteroid, and missed its launch date last year. An independent review into the missed launch found it was due to, among other problems, workforce issues at JPL.

“The Psyche Independent Review Board report cites a lack of staffing resources at JPL to support its current portfolio of missions across the laboratory,” NASA spokesperson Karen Fox said in a statement sent to The Verge. “As a planetary mission still in its early formulation phase, NASA decided to delay VERITAS for a launch no earlier than 2031.”

The argument given when the report results were announced was that, by delaying VERITAS, JPL staff would be freed up to work on other missions. However, Smrekar questioned this rationale at a NASA town hall during the conference, saying that while a shorter delay may have been justifiable, the longer delay “has nothing to do with JPL workforce, or the Psyche overruns” and that the mission was being “effectively martyred” for the sake of other missions going over budget.

“It’s not a simple delay,” Smrekar went on, clarifying that the money to pay for the engineering team had been completely wiped out. As a result, an experienced team that had been working together for over 10 years in some cases will now be disbanded. Before the delay, the mission had been on schedule and on budget.

Other team members concurred that while staffing may be a concern at JPL, their impression was that the delay was more to do with NASA budget issues than with efficiently redistributing staff. Some outside observers have speculated that NASA may have overcommitted by selecting two Venus missions in 2021 and realized too late that its budget wouldn’t stretch to cover both.

Cuts to budgets happen often enough, and scientists in the space field are accustomed to the disappointment of working on a mission proposal for years only to have it be passed over or canceled. But this situation is different because VERITAS had already been selected by NASA to be part of its Discovery Program. It was chosen to send an orbiting spacecraft to Venus, which will make multiple passes over the planet and use its spectrometry and radar instruments to build up detailed maps of the planet’s surface.

This situation is different because VERITAS had already been selected by NASA to be part of its Discovery Program

Historically, once a mission has been selected by NASA, those working on it can be confident that funding will be available. If a delay happens — as is not uncommon in large, complex missions — then a lower level of funding is typically made available to keep the basic essentials in place, called bridge funding, until full funding can be restored. This bridge funding keeps key personnel on the project so that they are ready to ramp back up once more funding is available.

In the case of VERITAS, after the announcement of the launch delay last year, the team asked NASA for bridge funding of around $20 million per year (about one-tenth of the original funding for 2024) so they could at least maintain mission essentials. Instead, virtually all of their funding has been cut, leaving them with a tiny $1.5 million per year.

This is a highly unusual situation for a selected mission because delaying and restarting missions is so expensive. NASA’s spokesperson said the agency expects to restart funding for the mission if the budget allows and if JPL passes an assessment in 2024.

But delaying the launch will cost more money in the long run. “The longer you delay VERITAS, the more it ends up costing in the end, and the harder it gets to have success,” Herrick, who is also a member of the VERITAS science team, explained. “This is counter-productive to NASA.”

That’s due to the difficulty of reassembling a team after a delay, as people who have been working on the mission for years have been transferred to other projects or are approaching retirement and may not be available later down the road. A new team will need more time and money to make up for that loss of experience.

Delays also cost money because specialist components used in the spacecraft design may no longer be available, necessitating a major redesign, which is a huge expense, notwithstanding inflation.

“The longer you delay VERITAS, the more it ends up costing in the end, and the harder it gets to have success.”

This sudden cutting of funding to an already selected mission is sending ripples through the wider scientific community. There is outrage in the planetary science community and “a strong feeling that this is unfair,” according to David Mimoun, a planetary scientist who has worked on NASA missions like the Mars InSight lander but is not involved with VERITAS.

The community is struggling to understand the rationale for cutting funding to an on-track mission. Other selected mission leaders will now have to contemplate the possibility that their funding could be gutted at any time, even if they are running on schedule and on budget. “It sets a precedent,” Mimoun said.

NASA has acknowledged the fervor over the gutting of the mission but has maintained that the cuts were necessary.

“The decision to delay VERITAS was gut-wrenching,” Lori Glaze, planetary science division director, said at another NASA town hall meeting last week about the agency’s 2024 budget. Glaze acknowledged the community’s concerns but cited factors affecting the planetary science division’s budget, like increased costs due to inflation, the effects of covid, and $80 million less in appropriations than the planned budget for 2022, leaving the division with little in the way of reserve funds.

Glaze went on to say that the selection of the next set of Discovery missions will likely be delayed to try to get VERITAS back on track. “The support for VERITAS is very, very clear,” she said.

A big part of the concern over the lack of bridge funding is the impact on international partnerships. The VERITAS mission will have contributions from the German, Italian, and French space agencies, who will be spending millions of dollars to bring components or whole instruments to the mission.

Dyar, the VERITAS deputy PI, said that agencies have already ordered expensive hardware, hired postdocs, and begun work on their contributions. Now, they are stuck with instruments they will struggle to complete because the VERITAS engineering team won’t be there to give them the support they need.

“It’s quite the imposition on the foreign partners,” Dyar said. There’s also a worry that by pulling support for the mission so suddenly, NASA runs the risk of ruining partnerships with experienced international engineers and scientists who are needed for future missions. Issues with the VERITAS mission could also affect other upcoming Venus missions, like the European Space Agency’s EnVision mission, which shares some hardware with VERITAS.

The discovery of active volcanism on Venus only increases the impetus to send a mission there

The discovery of active volcanism on Venus only increases the impetus to send a mission there, and VERITAS is the one mission of the three planned that is best situated to find out more about volcanism. VERITAS will create global maps of the planet with a much greater resolution than current maps from the 30-year-old Magellan mission, and it will be able to search for hotspots from erupting volcanoes and observe glowing lakes of lava on the planet’s surface.

The three Venus missions were planned out in a specific order for that reason. “At other bodies, like Mars, we sent Mars Odyssey first. And the reason we did that is we needed a good topographic map and a good geologic map. So that’s the logical sequence,” Dyar said.

The other two upcoming Venus missions, DAVINCI and EnVision, will offer exciting glimpses into the planet’s geology and atmosphere, but they are more targeted at specific phenomena. DAVINCI will drop a probe through the different layers of the Venusian atmosphere, taking pictures and collecting data during its descent. And EnVision will survey around a quarter of the planet’s surface while also looking deep into its core and high in the atmosphere.

The ideal situation from a science perspective would be to space out VERITAS and EnVision by as much time as possible. That’s because both will collect topography data, albeit in slightly different ways, so having the two missions separated will make changes to the planet over time visible. Now, the two missions may end up flying around the same time, limiting their potential for scientific discovery.

The missions have a broader application to planetary science as well, as studying Venus will help us better understand exoplanets. By studying features of Venus like its volcanism or its atmosphere, we can build a clearer picture of many of the exoplanets out there that we don’t have the opportunity to explore up close.

With exoplanet discovery and characterization being a key aim for flagship NASA missions like the James Webb Space Telescope and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, scientists argue that now is the time to be ramping up Venus exploration, not gutting the funding of a key mission.

“Venus, of all the objects in our solar system, is to me the one which has the most compelling urgency,” Dyar said. “It’s not just about Venus and our solar system. It’s about the universe.”

[ad_2]