[ad_1]

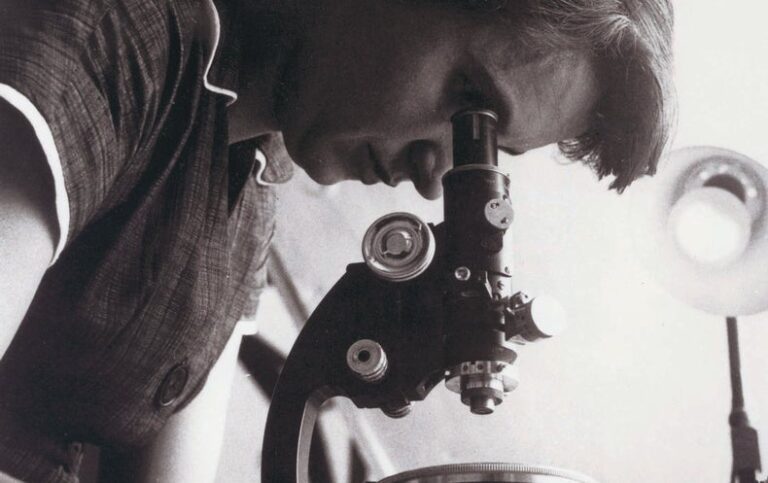

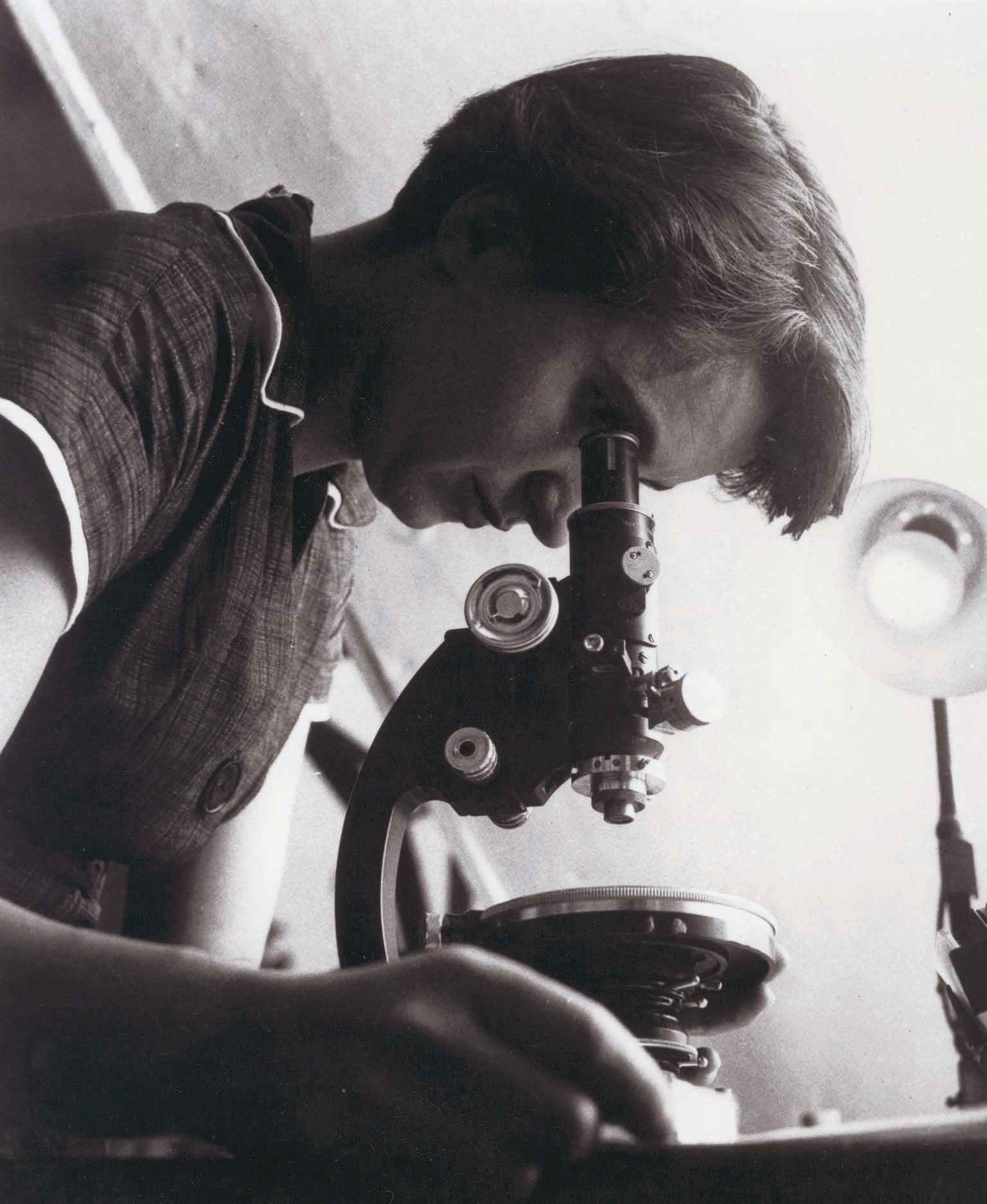

The two most famous prizes in the world are the Academy Award for work in film and the Nobel Prize for work in science and medicine. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences grants posthumous awards for people who won in their category but died before they could attend the ceremony and, occasionally, for special recognition, as when Audrey Hepburn was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1993. It’s time the Nobel Assembly did the same thing and awarded a posthumous Nobel Prize to British chemist and crystallographer Rosalind Franklin, whose research laid the foundation for the modern understanding of DNA.

Franklin was passed over for the prize in physiology or medicine when it was awarded in 1962 to biologists James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their discovery of the molecular structure of DNA. Previously no one could figure out how a simple molecule like DNA could carry large amounts of information. The double-helix structure solved the problem: DNA encodes information in the sequences of base pairs that sit inside the helix, and it replicates this information when the helical strands separate and re-create the matching strand.

The 1962 prize remains controversial, not just because three men won it while their female colleague was left out but also because the men relied on crucial information that they took from Franklin without her knowledge or consent: a set of x-ray diffraction images of DNA’s crystal structure. Franklin provided essential quantitative data on the structure in a report she shared with a colleague, who shared it with Watson and Crick. Later analysis of her laboratory notebooks showed not only that she had deduced the double-helix structure but also that she recognized that a structure based on complementary strands could explain how the molecule carried large amounts of genetic information because “an infinite variety of nucleotide sequences would be possible.”

Franklin published a paper on her research (with her graduate student, Raymond Gosling) in the same 1953 issue of Nature where Watson and Crick announced the conclusions for which they would be awarded the Nobel. But Franklin and Gosling’s paper, boringly entitled “Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate,” lacked the impact of Watson and Crick’s declaration that they had discovered DNA’s structure. In 1958 Franklin died of ovarian cancer, probably caused by her exposure to x-rays at a time when lab precautions were not what they are today.

Nobel rules state that prizes can be awarded only to living scientists, but many people believe that even had Franklin lived, the Nobel Assembly would have passed her over, just as it had all but three women before her: physicist Marie Curie for her role in explaining radioactivity and for isolating radium; radiochemist Irène Joliot-Curie for discovering induced radioactivity; and biochemist Gerty Cori, who showed how cells convert sugar into energy. Moreover, the award citation for the DNA work barely mentioned Franklin’s role. (Wilkins was not an author on the key 1953 DNA paper, either, yet he was included in the Nobel Prize.)

Scholars have argued that Franklin has been misrepresented. In a commentary published in Nature earlier this year, zoologist Matthew Cobb and historian of science Nathaniel Comfort explain that Watson’s best-selling 1968 book The Double Helix implied that Franklin didn’t comprehend the implications of her own data and in so doing minimized her role in the discovery. In fact, Cobb and Comfort demonstrate, “Franklin did not fail to grasp the structure of DNA. She was an equal contributor to solving it.”

The Nobel Assembly should right this wrong by awarding a posthumous Nobel to Franklin for her central role in the discovery of the double-helix structure. While they are at it, they ought to honor Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who discovered pulsars only to see the 1974 physics Nobel awarded to her thesis adviser—despite the fact that he had initially disbelieved her observations. Ditto for Chien-Shiung Wu, who proved that the “law of parity conservation”—that subatomic objects and their mirror images must behave the same way—was no law at all. (Eugene Wigner shared the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics in part for formulating that “law,” even though two male colleagues of Wu had won the prize in 1957 for disproving it!) And then there is Lise Meitner, the co-discoverer, with Otto Hahn, of nuclear fission. It was Meitner, along with her nephew, Otto Frisch, who proposed the term “fission” to describe what they had found, but Hahn won the prize.

It is the essence of science to recognize errors and correct them. It’s time for the Nobel Assembly to embody this ideal and do the same.

[ad_2]