[ad_1]

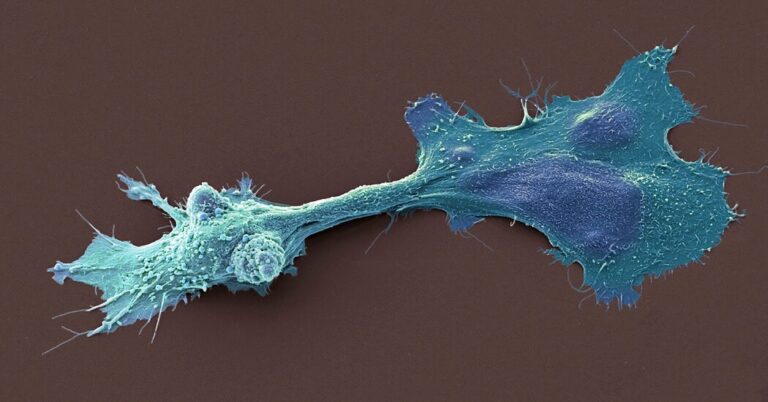

Over the past few years, a flurry of studies have found that tumors harbor a remarkably rich array of bacteria, fungi and viruses. These surprising findings have led many scientists to rethink the nature of cancer.

The medical possibilities were exciting: If tumors shed their distinctive microbes into the bloodstream, could they serve as an early marker of the disease? Or could antibiotics even shrink tumors?

In 2019, a start-up dug into these findings to develop microbe-based tests for cancer. This year, regulators agreed to prioritize an upcoming trial of the company’s test because of its promise for saving lives.

But now several research teams have cast doubt on three of the most prominent studies in the field, reporting that they were unable to reproduce the results. The purported tumor microbes, the critics said, were most likely mirages or the result of contamination.

“They just found stuff that wasn’t there,” said Steven Salzberg, an expert on analyzing DNA sequences at Johns Hopkins University, who published one of the recent critiques.

The authors of the work defended their data and pointed to more recent studies that reached similar conclusions. The unfolding debate reveals the tension between the potentially powerful applications that may come from understanding tumor microbes, and the challenge of deciphering their true nature. Independent experts said the current controversy is an example of the growing pains of a young but promising field.

Biologists have known for decades that at least some microbes play a part in cancer. The most striking example is a virus known as HPV, which causes cervical cancer by infecting cells. And certain strains of bacteria drive other cancers in organs such as the intestines and the stomach.

For decades, these links came to light slowly, because scientists lacked much of the technology available today. The search sped up drastically once researchers learned how to pull fragments of DNA from tumors. They then used computers to figure out whether the genetic material came from human cells or from other species.

In 2019, a team of scientists at the New York University School of Medicine used these techniques in a study on pancreatic cancer they published in the journal Nature. In many tumors, they found DNA fragments from a few different species of fungi. Further research led them to conclude that the fungi were driving the growth of the tumors.

These striking results attracted the attention of Dr. Peter Allen, a surgeon at the Duke University School of Medicine, who began looking for microbes in pancreatic tumors from his own patients.

But after searching 140 tumors, Dr. Allen and his colleagues couldn’t find a significant amount of DNA from any microbes, including fungi. “We didn’t find any true signature,” he said.

They then scrutinized the original study, whose genetic data had been uploaded to a public database. Dr. Allen’s team could not find a noticeable amount of fungal DNA in that data, either. They published their findings in Nature on Aug. 2.

The New York University researchers defended their work. “My group still stands with what we found,” said Deepak Saxena, one of the authors of the original study. He pointed to other data in line with his results.

In August, for example, researchers based at Tokyo Medical and Dental University reported finding fungi in pancreatic tumors from 78 out of 180 patients. And patients with tumors containing fungi were at greater risk of dying in the three years after their surgery, the study found.

Other researchers are questioning a 2020 report in Science by a team at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Examining 1,500 tumors from seven types of cancer, the study found that each type of tumor had a distinct set of bacteria, with breast cancer harboring a particularly rich variety.

But Jacques Neefjes, a microbiologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, and his colleagues could not detect bacteria inside cancer cells using some of the Weizmann team’s methods in their own collection of 129 breast cancer samples. “We do not find a single case,” he said.

In January, Dr. Neefjes’s group published a summary of their findings, which Science appended to the Israeli paper. They argued that bacteria found by the Weizmann team were byproducts of infections and are not, in fact, a normal part of breast cancer tumors.

Ravid Straussman, the leader of the Weizmann research, said that his group had done further research and that “the results clearly confirm the presence of bacteria in cancer cells.” He also said it was impossible to evaluate the claims from Dr. Neefjes’s team because they provided few details about their own experiment.

In a third study, published in Nature in 2020, researchers from the University of California, San Diego analyzed a government database of tumor DNA, called the Cancer Genome Atlas, and trained a computer to identify microbial DNA sequences from 18,000 tumors. The computer learned to recognize 33 different types of cancer based on their distinctive combinations of microbes.

“It looked like an incredible proof of concept,” said Abraham Gihawi, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of East Anglia.

But Dr. Gihawi and his colleagues changed their minds when they took a close look at the microbes that supposedly favored certain kinds of cancer. They seemed utterly out of place. Adrenal gland tumors appeared to host a virus that was previously only known to infect shrimp in the Gulf of Mexico. Bacteria only known to grow on seaweed seemed to prefer bladder cancer.

“This is a sure sign that something is going wrong,” Dr. Gihawi and his colleagues wrote in a letter they published on Aug. 9 in the journal Microbial Genomics. They deemed the seaweed bacteria and other out-of-place species “nonsensical.”

In a subsequent study with Dr. Salzberg, the researchers reanalyzed the data for themselves. “We’ve shown that the paper is wrong,” Dr. Salzberg said. The second analysis has been accepted by the journal mBio, he said.

Dr. Salzberg and his colleagues pointed to several possible reasons for the seemingly inexplicable results. In order to identify microbial DNA from tumors, for example, it’s first necessary to remove as many human sequences as possible. The critics say the San Diego team left some human sequences behind.

The critics also argue that errors can arise when scientists compare tumor sequences to microbial DNA to look for matches because some of that data is contaminated with human DNA. That’s how the DNA from a human cancer cell could appear to resemble the DNA from a seaweed microbe.

The San Diego team, led by Rob Knight, has responded at length to these criticisms. Dr. Knight said that he and his colleagues had used the best resources they could for their 2020 paper, and they went on to improve their methods for a paper they published last year in the journal Cell with Dr. Straussman’s group.

In that study, they used new techniques to remove more human DNA from their analysis. To predict different cancer types, they considered only bacteria with DNA that had gone through very rigorous inspection. “You still get tumor type-specific signatures,” Dr. Knight said.

In 2019, Dr. Knight co-founded a company called Micronoma to develop cancer tests based on his microbe findings. (Dr. Straussman serves on its scientific advisory board.) So far, the company has raised $17.5 million from private investors.

In January, Micronoma received a “Breakthrough Device” designation from the Food and Drug Administration for a lung cancer test, which will speed up its development for a clinical trial. Sandrine Miller-Montgomery, the chief executive of Micronoma, said that the trial would start in 2024.

“These critiques have not led to any change in our company’s plans,” Dr. Miller-Montgomery said.

Dr. Sven Borchmann, a physician-scientist at the University of Cologne, questioned whether the San Diego team was trying to turn its findings into a medical test too quickly, instead of doing more experiments to figure out what the results really meant. “I think they focused too quickly on application instead of understanding,” he said.

Still, Dr. Borchmann suspected that Dr. Knight’s team did find a number of species that would hold up to scrutiny, despite the recent challenge. “It doesn’t ruin the whole claim,” he said.

Qin Ma, a computational biologist at the Ohio State University, agreed that the new criticisms of the three papers didn’t change the overall weight of evidence gathered over the years. “Everyone agrees that microbes exist in tumors and are important,” he said.

But Dr. Ma and others acknowledged that the field was still searching for a standard set of tools that would provide highly accurate results. The current debate is moving the field toward that goal, they said.

“I would not be surprised if the disagreement causes both camps to innovate and push science further,” said Dr. Arturo Casadevall, a microbiologist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who was not involved in any of the studies. “This is a story of the scientific process at work.”

[ad_2]