[ad_1]

Once you are across the bridge onto Saint Helena Island, S.C., trinket shops and strip malls give way to fishing shacks and saltwater marshes. Secluded from the bustling tourist traffic just a bridge away, the island remains largely untouched. It preserves traditions fostered even before some of its residents’ ancestors were forced to traverse the more than 4,000 miles of ocean that separates the Saint Helena salt marshes from Africa.

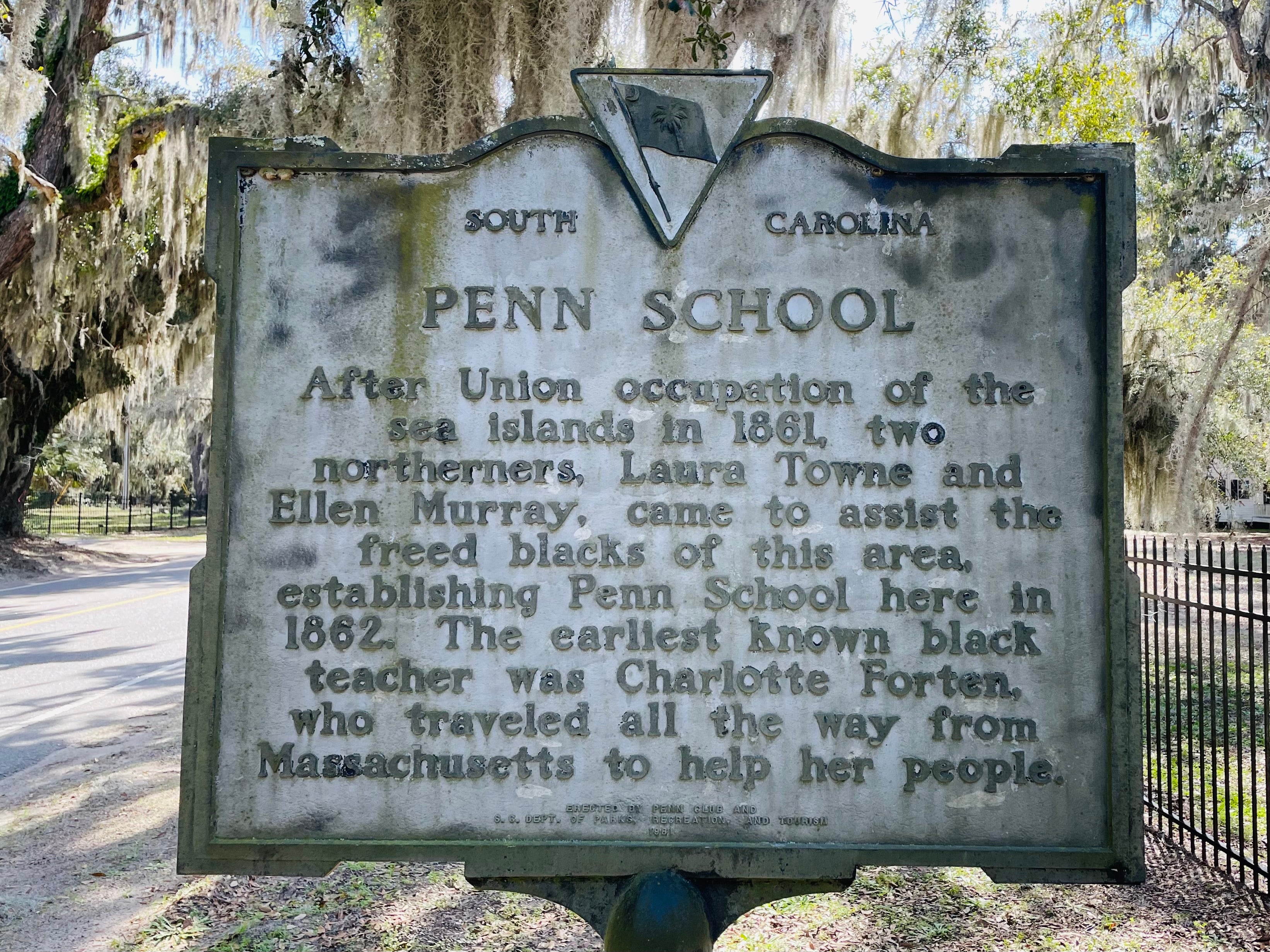

A logical first stop after arriving on Saint Helena from the mainland is the Penn Center, a school for formerly enslaved West Africans that’s now a cultural center. The Gullah Geechee people—members of an ethnic group living on Saint Helena and other islands and coastal areas in the U.S. Southeast—are descendants of Africans who were enslaved on plantations in the region. Their culture is still defined by a rich heritage of West African traditions adapted to fit life on the barrier islands where they lived, largely isolated from the rest of the American colonies before the American Revolution.

Tabby homes—built from a type of concrete made of broken oyster shells and sand—are still a common sight. Residents line their irrigation ditches with shells, hang blue bottles from trees to ward off evil spirits and weave intricate baskets with seagrass found along the coast. There are still an estimated one million Gullah Geechee people living on the coastal areas between Jacksonville, Fla., and Jacksonville, N.C., according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. Many still make their homes on what are called heirs’ properties: land that’s passed down without deeds from generation to generation.

Saint Helena is one of the few remaining sea islands in the U.S. that recalls an earlier era. Some Gullah Geechee people have held onto their lands since the first enslaved people arrived in what would become South Carolina in the 16th century. Elsewhere along the coast, Gullah Geechee families have yielded their lands to developers of hotels and vacation homes and upscale gated communities. Dating from the end of the Civil War, Gullah Geechee families have lost more than 14 million acres of family property, and only around one million acres owned by the formerly enslaved group is still in family hands.

Occupying 64 square miles, Saint Helena is one of the centers of Gullah Geechee culture. It’s a vast swath of pristine coastal land dotted with maritime forests and salt marshes. Gullah Geechee people on Saint Helena still own their land because their ancestors put up cash to obtain deeds in the 19th century. On other sea islands along the South Carolina coast, formerly enslaved people were given the lands initially and then were pushed off them after Reconstruction. After Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and Andrew Johnson, who held deeply racist beliefs, became president, the land was returned to former plantation owners.* But on Saint Helena, Gullah Geechee people bid on land at auction and split it up into family compounds such as the one owned by the Heyward family, who still live on their property more than 150 years later. The island has a cultural protection overlay (CPO), a zoning ordinance that gives protection against development of these lands.

Those who remain on Saint Helena hope to stem the tide of generational changes elsewhere in the Gullah community by refusing to give up titles on their lands. Their self-sufficiency—adapted to living in harmony with the coastline, especially in how the land is developed—may prove vital to preserving the South Carolina coastline against rising seas in the years ahead. From hunting deer, wild boar and squirrels to cultivating rice, watermelon, sweet potatoes, red peas, okra, peanuts and butter beans, the Gullah Geechee know how to thrive on land that others have found punishing. Like the tides, their way of life has an ebb and flow to it that is built and rebuilt as the waters rise and retreat.

Beside the Spanish-moss-draped live oaks, whose canopies are so thick that a cloudless sky hardly peeps through, stands Joanna Heyward, a soft-spoken cultural center volunteer with tight black curls and a warm smile. Her family has owned land on Saint Helena for six generations. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather bought land on the island during the Civil War at a cost of $1.25 an acre. He and his brothers had to pick 400 pounds of cotton for each dollar they earned to buy the land from former enslavers. They put together enough savings and ended up with enough cash for 30 acres. “Today our family still owns about 20 acres of that land,” Heyward says.

Heyward’s experience mirrors that of Marquetta Goodwine, known as Queen Quet, chieftess of the Gullah/Geechee Nation. Goodwine has spoken on behalf of the Gullah Geechee people before the United Nations and the International Human Rights Association for American Minorities. She’s also worked with Representative James Clyburn of South Carolina to establish the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor along the southeastern coast. Both sides of her family are Gullah Geechee. She wears a violet silk gown embellished with gold thread and seashells woven into her braided hair. Goodwine tells me that Gullah Geechee people were fearful of purchasing their land, yet they knew having a deed was a powerful means to achieving prosperity. Land auctions were frightening for the formerly enslaved, who had once been sold at auction themselves. “But this was not an auction about you or family. This was about buying up the land that had been left behind,” she says.

The Gullah Geechee have retained over the centuries an acute awareness of the fragile coastal ecosystem where they live. “Our people don’t traditionally build their homes into the coastline but rather into the center of their acreage,” so it’s less susceptible to hurricanes, Goodwine says. Smaller and lighter homes don’t require as much cement or packed soil to sustain the weight of a structure in the sandy soil. “The water will eventually break through concrete no matter how many times you rebuild,” she says. Mother Nature always wins.

More than half of the original salt marshes in the U.S. have been filled in to create land for housing and industry along the coasts. When a new resort is built by filling in marshland, water from storms has nowhere to drain. Hilton Head Island, S.C., Tybee Island, Ga., Saint Simon’s Island, Ga., and other islands along the South Carolina and Georgia coastline now experience flooding more often. Across the Southeast, losses caused by recent hurricane winds, land subsidence and sea-level rise average $14 billion per year. An EPA report found that just one acre of wetland can store up to 1.5 million gallons of floodwater. “Without the salt marsh holding the coastal wooded habitats known as maritime forest in place, and without our oyster beds holding the salt marsh in place, you start to erode the sea islands,” Goodwine says.

The barrier islands are landforms that developed from the buildup of tidal sand deposits. They run parallel to the coastline and are prominent along the Eastern Seaboard. The islands themselves are an important line of defense when it comes to protecting the coastline from storms, and their marshes absorb the onrush of waters from a storm surge. A July 2022 study in Nature Geoscience found, however, that sea-level rise will cause these islands to move closer to the shore, which diminishes their ability to act as a buffer between the ocean and beachfront property.

The importance of preservation of Gullah Geechee culture—and the consequent protection of island wetlands—was recognized in January. The island’s planning commission blocked a controversial 500-acre community on Saint Helena where developers intended to turn land not owned by Gullah Geechee people—a section known as Pine Island—into a luxury golf resort. Jessie White, south coast office director at the Coastal Conservation League, says that cultural protection overlay zoning has been crucial to keeping land out of the hands of developers—unlike on Hilton Head, where property was bought up from Gullah Geechee people, and those who remained were later pushed out by higher taxes. “Inflating taxes has long been used to remove people from their property,” White says.

Three hours south from Saint Helena, along the Georgia coast, Gullah strongholds such as Sapelo Island, Ga., have also had some recent victories. In 2020 residents of Hogg Hummock community on Sapelo Island, a Gullah community on a remote island that is only reachable by ferry, won a federal lawsuit that found that they were being discriminated against and excluded basic services on the basis of race. The county seat of McIntosh County also agreed to freeze residential property taxes until 2025. Still, change is apparent. The contrast between tiny wooden and tabby homes on family compounds and newer, modern homes with double the square footage built atop cemented stilts is apparent. “Every time I go back, I get a lump in my throat when I see the new construction,” says Courtney McGill, a member of the Hogg Hummock community who grew up on Sapelo and whose family still has a home on the island. Local governments of islands such as Saint Simon’s and communities in North Charleston, S.C., have similarly taxed Gullah Geechee off their land.

Two years ago Gullah Geechee people on Saint Helena fought to block another development on Bay Point Island, a strip of sand used by a Gullah Geechee fishing community there. Developers wanted to build an ecotourist resort with 50 cottages, a spa, a fitness center, restaurants and bars, all of which would have required the construction of 10 septic systems.

The developers likely planned to fill in the marsh, which would have destroyed the habitat of many marine species. “These waters are already changing,” says Ed Atkins, a Gullah fisherman who has been working the waters for 60 years. “There used to be a lot more fish in these waters then there is now. [There are] less blue crab and oysters, too.”

Providing shelter, food and nursery grounds, salt marshes are one of the most critical habitats for ocean biodiversity for 75 percent of U.S. commercial and recreational fish species, including white shrimp, blue crab, red drum and flounder—all foods that are important to the Gullah Geechee diet.

As sea level rises, salt marshes that once drained at low tide continually flood. Sea level around Charleston has risen as much as 10 inches in the past 73 years. As a result, marsh plants, which thrive in brackish waters, germinate farther inland in what is called marsh migration. This natural adaptation only works if the salt marsh has a place to go, says Lora Clarke, a Charleston-based coastal ecologist at the Pew Charitable Trusts. The five states that will potentially undergo the most extensive marsh migration during this century are Louisiana, Florida, North Carolina, Texas and South Carolina, which collectively account for 82 percent of the nationwide land area where marsh migration could occur, according to a June 2022 study in the journal Science Advances.

New development along the coastline could block the movement of plant life inland. “We need to make sure that we maintain those undeveloped spaces that allow the marsh to migrate,” Clarke says. Pew is working with the Gullah/Geechee Nation, the Coastal Conservation League and a number of other organizations on the South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative, a 15-year plan with the goal of conserving one million acres of salt marsh in the Southeast.

Just beyond the salt marsh, farther out in the ocean water, lies the oyster reef habitat where clusters of dead and living shells fuse together under the brackish tides. Harvesting oysters creates a stable form of nourishment year-round for the Gullah Geechee, and the practice became an important cash crop in the South after slavery as the cultivation of cotton and indigo came to a halt. Preserving the Gullah’s traditional harvesting methods has become increasingly important to protect this source of income.

Bubba Green of Gullah Man Oyster and Seafood Company on Saint Helena says that South Carolina oysters, a saltier variety of the shellfish, have become so popular that they’re being overharvested. This makes it harder for Gullah Geechee people to feed their families with this still-important food staple. At one point in time, Green says, nearby Bluffton, S.C.,, had as many as five oyster shucking houses. His father, Bill Green, is a famous Gullah chef and owner of the well-known Gullah Grub Restaurant on Saint Helena. I meet Bubba Green in his family’s white clapboard restaurant, where father and son still work together daily to cook up locally caught fried shrimp and oysters and serve South Carolina Low-Country specialties such as oyster stew. The two look almost like twins, with the same height and build and round faces, wide grins and well-kept beards—only Bill’s beard is lightened by flecks of gray.

Bubba Green has an encyclopedic knowledge of oysters: their biology, breeding and susceptibility to a changing climate. “The oysters aren’t there anymore, and when they are, they’re not being harvested the right way,” he says. Traditional harvesting is being taken over with the development of the land. Sustainable oyster reefs are built on the premise of taking what is needed while also protecting the reef. “We call it cull in place,” Green says. This means knocking the baby oysters off of a cluster of the mollusks when you’re harvesting the adults so that the babies can continue the cycle of life. “If you knock the foot [of each oyster] off and take the whole cluster, you’re killing thousands of baby oysters that will never grow into adults,” he says.

Oyster reefs aren’t just important for feeding the population. They’re also crucial to coastal ecology. They shelter other prized marine species such as blue crabs, flounder, perch and mackerel. And according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, a single oyster can filter more than 50 gallons of water a day. But perhaps the most important reason for making reef preservation a priority is the oyster bed’s role in providing storm protection. It slows down tidal incursions and protects waterfront communities from the effects of storm surge and flooding. Oyster reefs “dissipate wave energy” and act as barriers to slow the force of storm surges along the coast, according to a June 2019 Nature study.

Strength in the face of adversity remains pivotal to the Gullah Geechee way of life. “We have resiliency built into our DNA after surviving on these lands for centuries,” Goodwine says. The community’s adamant stance in holding out against developers and its protectiveness of salt marshes and traditional fisheries will determine whether the barrier islands remain intact.

After our chat, I follow Goodwine and Atkins back to the parking lot where Atkins shows me the bucket of eastern oysters he plucked from the salt marsh that morning. He smiles over his fresh catch of shellfish and ends our conversation with a resoluteness that gives hope that the Gullah Geechee people may prevail in preserving their culture and the islands. “A scientist can tell me what they think is going to happen, but I know these waters better than they ever will,” he says.

*Editor’s Note (4/6/23): This sentence was edited after posting to correct the description of Andrew Johnson becoming U.S. president after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

[ad_2]