NASA is a step closer to landing even larger vehicles on Mars.

Following being launched aboard the last United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket blastoff from the West Coast on Wednesday (Nov. 10), an inflatable heat shield technology demonstrator called LOFTID appeared to make a flawless journey to space and back. If that is indeed the case, this mission marks a keystone moment in NASA’s long journey to eventually bring humans to Mars.

Splashdown of the Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator was nose down, which was exactly as planned. It even inflated in the ocean, roughly 500 miles (800 km) away from Hawaii — a bonus milestone for the engineering team.

“This is one of the most critical technologies that we’re establishing right now with this mission, and also with that first successful orbital flight and recovery,” Jim Reuter, NASA’s associate administrator for the space technology mission directorate, said during the NASA Television livestream just after the splashdown.

Related: Next-generation inflatable Mars landing gear to get a test during launch on Nov. 1

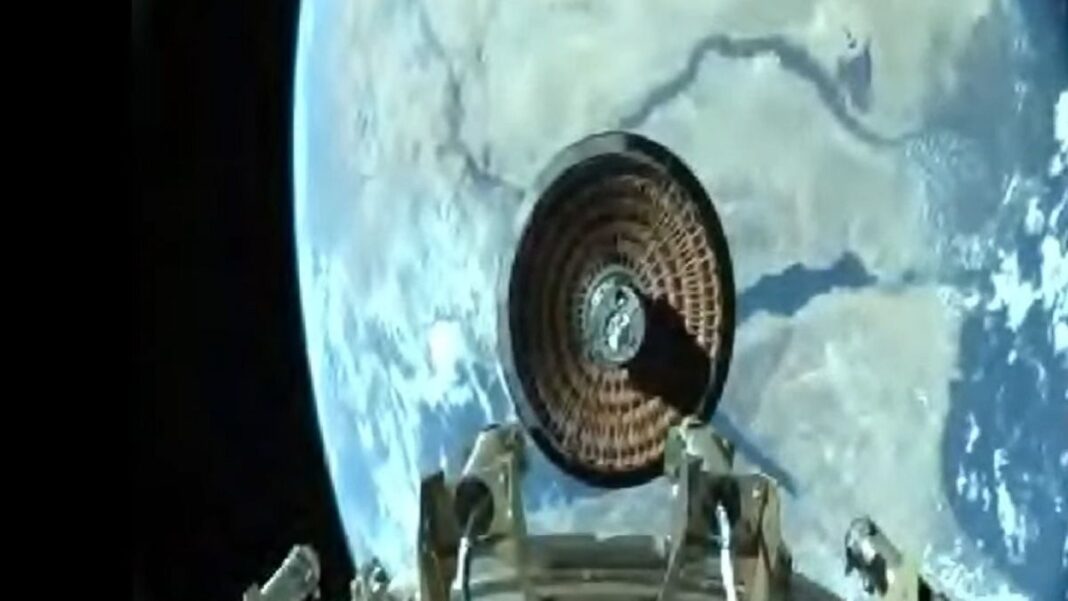

After deployment in space, NASA visually confirmed via the video livestream the full inflation of LOFTID at about 78 miles (125 km) in altitude, marking the beginning of the re-entry. Telemetry was briefly lost as the demonstrator made its way back to Earth, but everything turned out well in the end.

The inflatable technology splashed down just 5 miles (8 km) from the Kahana II recovery vessel, allowing for an easy retrieval, and LOFTID jettisoned its flight recorder as planned for data collection.

“This is a great, great opportunity to get flight data and see how it actually performed,” Greg Swanson, LOFTID instrumentation lead at NASA’s Ames Research Center, said during the same livestream. “We know it performed well enough to make it great,” he added of the mission.

The $93 million LOFTID, which launched alongside the Joint Polar Satellite System-2 (JPSS-2), is an expandable aeroshell designed to slow a spacecraft’s entry through the Martian sky and reduce the amount of heat created by atmospheric friction. NASA says the tech represents one solution to landing in the ultra-thin Martian atmosphere, which makes landings especially delicate because spacecraft encounter only a fraction of drag compared to Earth’s atmosphere.

Parachutes are not enough to get even smaller payloads down on Mars; for example, the golf-cart-sized Spirit and Opportunity rovers tumbled upon the surface in a set of air bags that softened the fall. The larger Curiosity and Perseverance rovers required a rocket-powered sky crane to bring the SUV-sized vehicles to the surface.

The sky crane probably hit its maximum in getting the 1-ton masses of each of the two larger rovers down to the surface, however, which is why NASA is testing out this inflatable aeroshell to land humans and the cargo they require to live on the Red Planet. The flying saucer shape is designed to squeeze into a conventional rocket during launch, but expand and inflate when they arrive at the Red Planet and its atmosphere. (Parachutes would also be used to ensure the payload’s safe arrival on Mars.)

To be sure, Mars human landing dates remain far in the future while NASA remains focused on its Artemis program. Artemis I has just ridden out Tropical Storm Nicole that hit the Floridian east coast overnight. It may be launching on its uncrewed journey around the moon on Nov. 16, kicking off a series of missions that will include a moon landing on Artemis 3 later in the 2020s.

There’s a lot of tech that could transfer between human moon missions and excursions to Mars, although LOFTID is an exception as the moon has no appreciable atmosphere. Mars expeditions for humans will likely take place at least in the 2040s. In the shorter term, NASA and the European Space Agency plan to launch an uncrewed sample return mission to pick up the most promising cached rocks from the Perseverance rover’s work on the Red Planet.

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of “Why Am I Taller (opens in new tab)?” (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).