[ad_1]

“What’s the meanest thing anyone ever did to you?” my nine-year-old asks while I’m driving him over to the next town for his weekly Taekwondo class. Always, for some reason, our best discussions take place in the car. “I don’t think there have been too many mean things,” I say, which feels mostly true, especially in a relative sense, or maybe I just can’t recall, or my brain is wearing blinders either on his behalf or mine. I think for a moment.

“Well, when I was about your age, a bunch of girls in my class signed a hate petition against me,” I tell him. “It said: We all hate you. Then there were a bunch of lines for the signatures.” I laugh. It now sounds so cruel and formal to me that it’s almost funny. “Ouch,” he says.

As I turn left, turn right, drive along a two-lane causeway, I explain that the hate petition was not a surprise; they’d been going around. Somebody in my class spearheaded the idea and there was a new victim every few days. At a stoplight, I glance at him in the rearview mirror. His face is scrunched with confusion, perhaps some protectiveness. I know it’s weird thinking about your mom when she was a kid, let alone imagining other kids messing with her. I pause, hold myself back.

“Sometimes kids can be cruel,” I say, which is something my mother occasionally said to me. I pause again, in case he has something to share. We drive for a while, inside our own thoughts. I decide not to tell him about the addendum at the bottom of that petition, the part that stung most. It said, “And we hate your hair.”

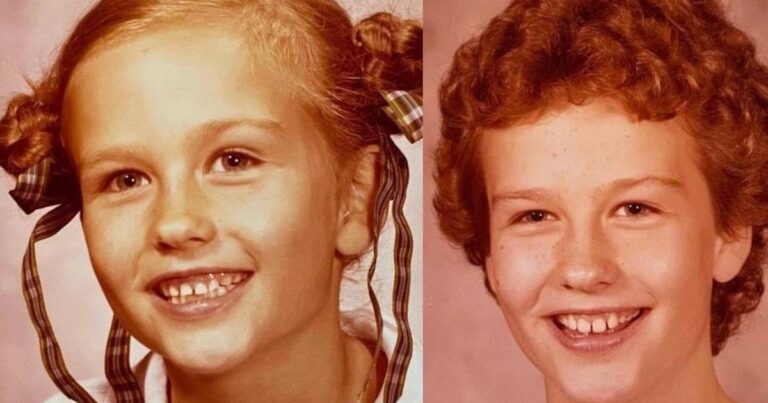

Every morning before school, my mother used her thin, freckled hands to pull my hair into various styles: French braid, high bun, low bun, or two side buns like Princess Leia. Ponytail, two ponytails, half-up- half-down. Sometimes she looped two braids at the side of my head like puppy ears. I watched in the mirror as she hunched over every creation. She clenched a comb between her teeth then deftly grabbed it in order to section-off different parts of my head with precision. If a braid turned out bumpy or lopsided, she’d calmly start over. I was always delighted with the result.

With every style, my mother incorporated a ribbon tied in a bow. We picked them out together to coordinate with what I was wearing that day. In the bathroom, we had a drawer full of ribbons we’d purchased from spools at the fabric store. Gingham, plaid, and polka dots were all coiled in there like so many colorful garden snakes.

I often got compliments on my hair from teachers or bank tellers or someone passing by on the street. Were these compliments for me or my mother? It didn’t matter, because we both had fun with those hairstyles and those ribbons. Did other girls in my class ever compliment my hair? I don’t remember, but apparently not. In fact, the signatures on the petition documented that they, quote, hated it. I didn’t even consider showing my mother the hate petition or telling her about it. She didn’t have anyone other than my brother and I. Her parents were gone. So were her siblings. She’d lost touch with her cousins, aunts, and uncles. After our dad moved out, she resolved to love us enough for two parents and for all the extended family she (and therefore we) didn’t have. She signed us up for after-school classes and drove us to plays, activities at far-flung libraries, and performances of all kinds. Sometimes we got ice cream cones at Baskin Robbins. Mint chip. She laughed at our jokes and listened to every single word we said.

When I read that line about my hair, it occurred to me suddenly that I might be spoiled. There was an awful character on the TV show, Little House on the Prairie: Nellie Olesen. She got everything her heart desired and always had a smug look on her face. The perfect ringlets of her hair somehow signified she was a jerk. Did my carefully styled hair say the same thing about me? I mulled this over for weeks. I certainly didn’t get everything I wanted. For example, no matter how many ribbons were in that drawer, the bitter fact remained: I didn’t have an intact family like most kids in my class, like all the girls who signed the petition.

Though my mother kept doing my hair before school, I told her I didn’t want ribbons anymore. Truthfully, I still did want these accessories, I just didn’t want to be hated because of them. I knew exactly how much my mother loved me. I felt it not just when she did my hair. I felt it almost every minute. For the first time, this seemed like something I should be ashamed of.

I decided to get all my hair cut off the next year. I also got a tight perm. I was quite pleased to look like Orphan Annie. My mother cried in the hair salon that day. It’s plain to see, in photos, that the style looked terrible on me, but she claimed, through tears, I was beautiful no matter what. I know now that at least some of those tears were because she was watching me grow up. My mother has now been gone for several years. I’ve worn my hair long and pulled back most of my life. Those ribbons are now in my basement inside a set of plastic craft drawers. I use them to wrap presents.

We pull into the lot of the strip mall containing this class my son loves and I love taking him to. They’re not ribbons and not exactly the same, but he enjoys earning all those colorful Taekwondo belts. We’re almost two minutes late, something Master Jung frowns upon. But I need to know. “What’s the meanest thing anyone’s done to you?” I ask, trying to sound as casual as he had. I put the car in park and twist around to look directly at him. I love him every minute, every second. “Nothing,” he shrugs. I can’t tell if his eyebrows, lifted up like that, mean he’s being honest, or hiding something that happened to him or something he did, or if he’s just aware of the time displayed on the dashboard. “Ok.” I pat his knee. Maybe I’ll ask again on the way home. Or maybe I won’t push it.

He stops before he opens the door, his fingers on the door handle. “So did you sign any of the hate petitions going around?”

I shake my head. “I don’t think I did,” I answer calmly, but I’m startled by the question. He waves to me right before he heads inside and I wave back with a smile, hoping what I said was true. The fact that I can’t exactly remember makes me wonder. After all, kids can be cruel.

Jocelyn Jane Cox is a former figure skating competitor and national-level coach with an MFA in Creative Writing. She is working on a collection of personal essays and humor pieces about the unlikely intersection of figure skating, driving, and parenting. She lives in New York’s Hudson Valley with her husband, her son, and the antique eyeglass collection she started long ago with her one-of-a-kind mom.

[ad_2]