[ad_1]

In 2016, while doing routine testing of NASA’s Juno spacecraft, the mission team discovered that parts of the engine weren’t working the way they expected.

The spacecraft, which had arrived at Jupiter in July 2016, was orbiting the giant planet every 53 days and due to accelerate, shortening that period to 14 days. Given the engine concerns, the Juno team decided not to risk the change, instead keeping the spacecraft in the longer, wider orbital period. And when the mission’s success earned it an extra 42 passes of the planet, the team got an unexpected opportunity — to snatch close glimpses of some of Jupiter’s moons.

“It was fortuitous, as we transitioned to our extended mission, that we were able to do close flybys… of the moons,” Scott Bolton, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio and principal investigator of NASA’s Juno mission, said at a news conference on Wednesday (Dec. 14) held as part of this week’s American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting.

Related: NASA’s Juno spacecraft snaps its most detailed view of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa

Juno’s observations of Jupiter and its moons are revealing new insights and will serve as the foundation for future missions to the moons. One of these missions, the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), has already used Juno’s images of the largest moon in the solar system, Ganymede, to create a detailed map of Ganymede’s surface. The map builds on data collected by NASA’s Voyager missions, which passed by the moon in 1979, and the Galileo mission that studied the Jupiter system in the 1990s and ’00s.

The resulting map shows off the stunning variety of features on Ganymede’s icy surface. “It has dark terrain in it and it has this bright terrain,” Bolton said.

“It has linear features that look like they’re probably driven by tectonics, and it has these big white spots where there’s craters that are producing fresh, clean ice,” he added. “It’s a very diverse place.”

Juno has also peeked below that interesting surface with the spacecraft’s microwave sensors, which highlight what might be going on beneath the surface of Ganymede and another of Jupiter’s icy moons, Europa. The data reveals not only that a patchwork of hotter and colder areas exist under Ganymede’s surface, likely resulting from its different terrain types, but also that the moon’s ice makes it highly reflective. The microwave readings made Ganymede appear even colder than previous measurements, indicating that the moon’s ice is reflecting back some of the heat that reaches the moon.

This reflective effect was even more extreme on Europa, Bolton said. Juno was also able to use one of its navigation cameras, which use low-light detection of surrounding stars to navigate, to photograph the night side of Europa.

“You’re looking at the night side lit up by Jupiter-shine,” Bolton said. “So it’s a very innovative way to take a look at Europa and use all of our sensors.” Jupiter-shine, like Earthshine on our moon, happens when Jupiter reflects the sun’s light and projects it dimly onto Europa’s surface.

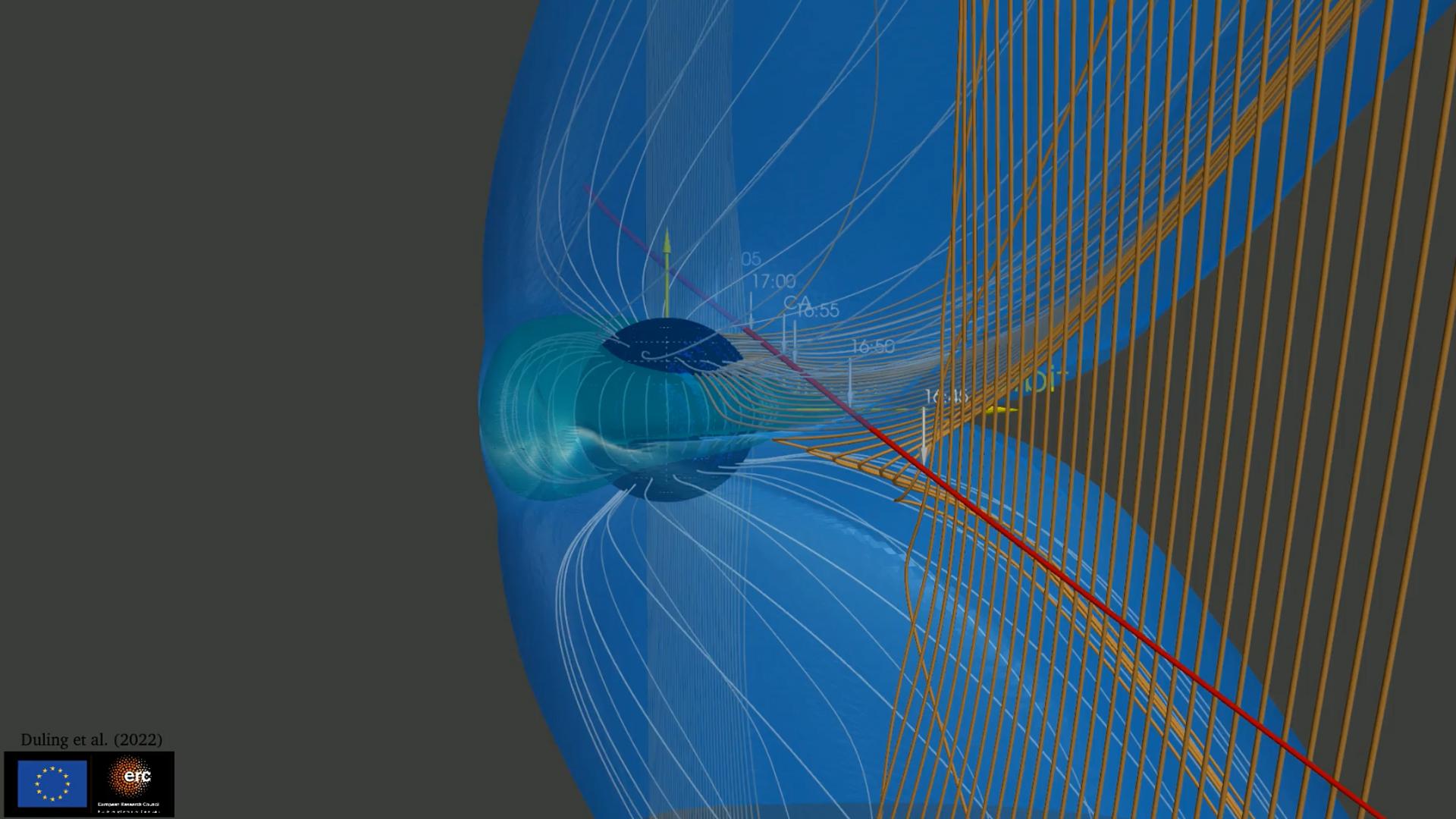

Juno also took the opportunity to examine a unique aspect of Ganymede, its magnetic field. Ganymede is the only moon in our solar system known to generate its own magnetic field. Juno gathered data showing that Jupiter’s and Ganymede’s magnetic fields connect and disconnect, releasing ultraviolet radiation in the process.

“You can get a snapshot of looking at the entire magnetic field geometry of Jupiter and Ganymede connected together by looking at the UV observations,” Thomas Greathouse, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute who studied these emissions, said during the news conference.

And of course, Juno’s primary camera has been hard at work during these flybys. Stunning images taken by Juno show details of features “hiding in plain sight” from earlier images, like those from the Voyager mission, Candice Hansen, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, said during the news conference. Hansen is a co-investigator on the Juno mission and began her career working with Voyager’s imaging team.

The extremely high-quality images the Juno took include a patera on Ganymede, a feature resembling a volcanic crater. Juno was also able to take new photographs of Europa’s surface, which is smoother and less covered in craters than the mottled surfaces of some of Jupiter’s other moons, meaning its surface is very young, Hansen said, which agrees with previous data.

Of course, Juno is still photographing Jupiter itself. Among Juno’s latest snapshots are striking images of Jupiter’s turbulent clouds, including its northern cyclones, appearing as swirling structures of green-gray and pale yellow against a blue backdrop straight out of a Van Gogh painting.

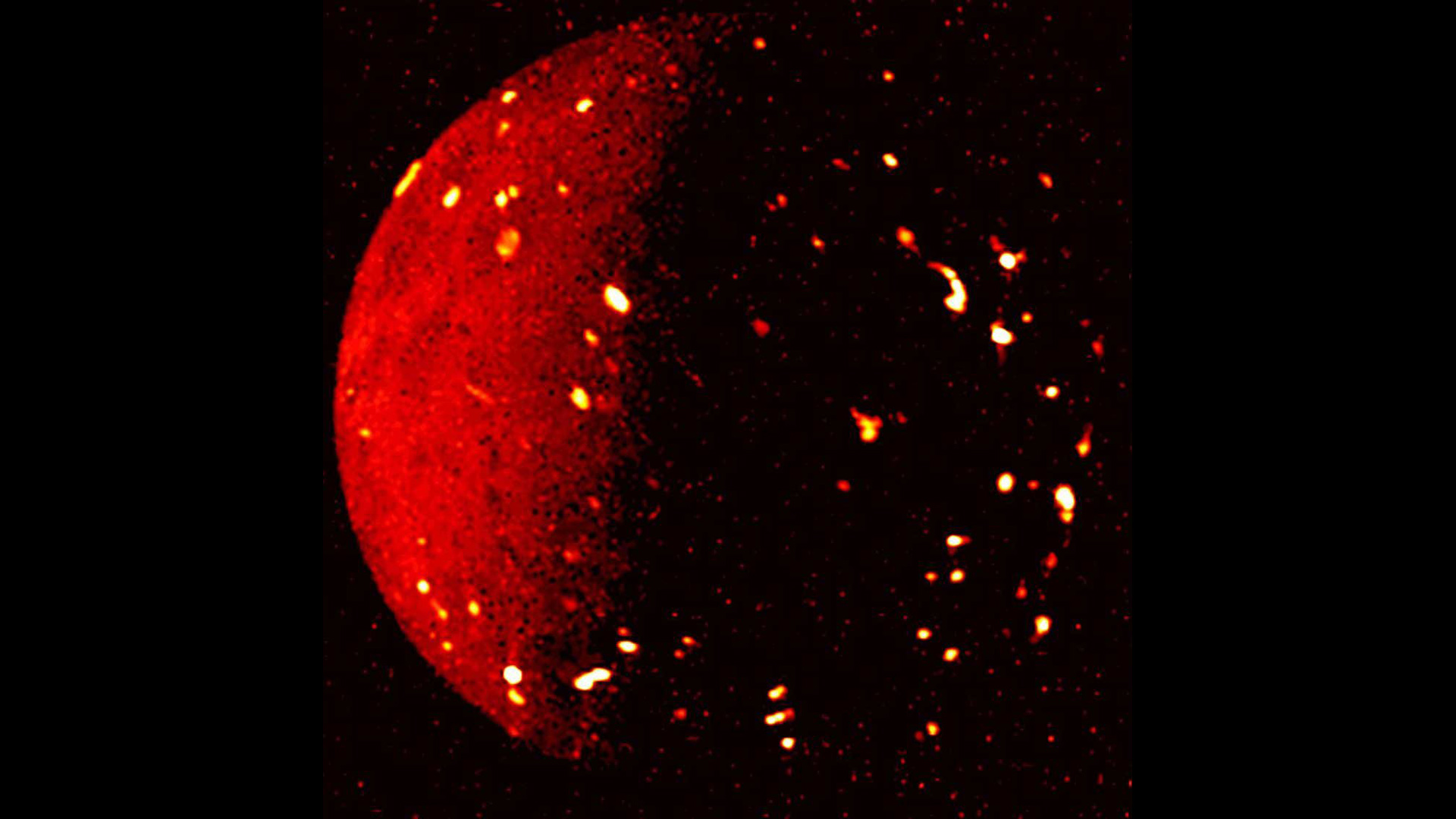

The mission is also one of the first times that scientists have gotten to see the poles of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io. Infrared photos of the moon taken during a flyby on July 5 show many glowing hotspots, and more of these hotspots were detected at the poles than the equator of the moon, which surprised scientists, Bolton said. Juno flew by Io once again on Thursday (Dec. 15), taking the closest images to date of the moon.

Even with the mission extension, Juno won’t last forever. In the next few years, the intense radiation around Jupiter and its moons may destroy its equipment. Even if that doesn’t happen, Juno will eventually run out of propellant, making it unable to turn toward Earth and send back data. Although the team originally planned to intentionally crash the spacecraft into Jupiter to protect potentially habitable moons like Europa, its current trajectory will eventually send the spacecraft crashing into Jupiter on its own, Bolton said, where it will burn up in the thick atmosphere. Bolton added that this hands-off approach is still going through official approval, but will likely be the easiest way to dispose of the spacecraft.

Future missions, like NASA’s Europa Clipper, due to launch in October 2024, and JUICE, due to launch in April 2023, will build on what scientists have learned from Juno — and the moon mysteries that remain. For example, Juno was not able to observe Europa’s mysterious watery plumes, which may allow scientists to peer into the global ocean scientists think lurks under the icy shell.

The JUICE team has already used data from Juno, Bolton said, including to make the map of Ganymede shown at the beginning of the news conference. The team is “trying to figure out what to look at with their cameras and sensors,” he said. “And so they’re already looking at the regions that we’ve identified in higher resolution than we had before and starting to make plans.”

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]