[ad_1]

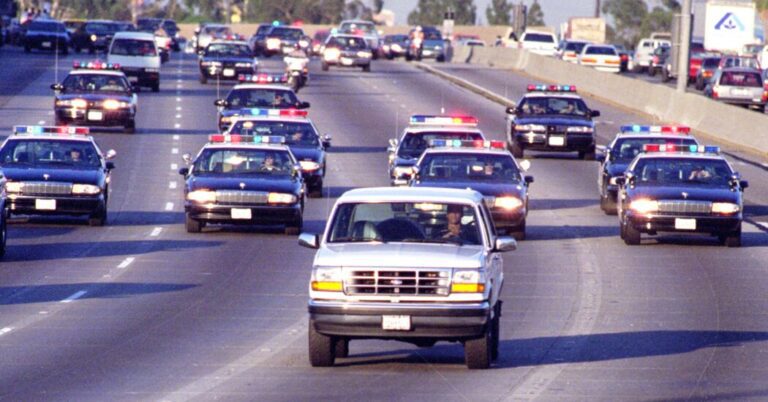

It would become an indelible memory for those who could not help but watch and watch and watch: a white Ford Bronco steadily traveling along the cleared freeways of Southern California, a trail of police cars not far behind.

Its passenger, of course, was O.J. Simpson, and the two-hour chase on June 17, 1994, that interrupted regular programming transfixed a nation.

“I watched it until it ended. I wasn’t getting off the TV. Who was getting off the TV on a chase like that?” said Richard Smith, 67, who gathered that day with his family to see it all unfold on television in their South Los Angeles apartment.

The saga of Mr. Simpson, from the chase to the criminal trial to the aftermath, would be followed, debated and dissected closely by millions, etching itself into Los Angeles history and thrusting the city into what seemed the center of the universe.

On Thursday, as news spread of Mr. Simpson’s death at 76 from cancer, many residents were forced to reminisce about events that felt distinctly personal, touching on issues of race and celebrity that had long hit close to home in Southern California. And the case had played out on their home turf only a handful of years after the Rodney King beating and the Los Angeles riots.

Mr. Simpson, at the time, was seen as someone who had transcended the tense and deadly relationship other Black Angelenos had with law enforcement. Soaring above his impoverished beginnings, he had carved out an international show business career and lived in the affluent enclave of Brentwood.

And more than most celebrities, he was a local fixture. Rare was the Angeleno without a tale of an O.J. sighting, now golfing in West Los Angeles, now dining on Greek food at John Papadakis’s taverna in San Pedro, now cavorting on the sand outside his vacation home in Laguna Beach.

Before the murder charges and the domestic violence reports surfaced, Mr. Simpson had been an icon, revered for his sports prowess as much as his commercial success in films and role as the spokesman for the Hertz rental car company.

“It made you want to be something better,” recalled Mr. Smith, who still lives in South Los Angeles.

Mr. Smith’s neighborhood would soon be captivated by the trial of Mr. Simpson, after he was accused of killing his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman. Unfolding on live television, the trial dragged on for 11 months, and everyone had opinions. “All day long, every day, people were stressing and going through arguments about, ‘He did do it, he didn’t do it.’ I mean, it was going down,” Mr. Smith said.

Along the way, villains and heroes were created depending on where you stood, becoming almost caricatures in a city known for creating dramatic story lines.

A tabloid bonanza, the trial was also a core sample of Los Angeles at the dawn of the 21st century: a Black celebrity defendant surrounded by all-star lawyers; a white Los Angeles police detective, accused of racism; a Midwestern show business aspirant living in the guesthouse; the Orange County family of the defendant’s ex-wife, the stricken relatives of the Westside waiter who was slain with her; the housekeeper, an immigrant from El Salvador; the judge, a son of Japanese Americans who were sent to incarceration camps during World War II.

“Things happened that no one would believe,” said Laurie Levenson, a Loyola Law School professor who became an early legal celebrity doing TV commentary on Mr. Simpson’s trial. She said she still celebrated Passover with lawyers and members of the press with whom she bonded during the case.

“The thousands of reporters. The wall-to-wall network coverage, even interrupting soap operas. The glove demonstration. The race issues. The domestic violence issues. The cameras in the courtroom changed the way trials are viewed to this day in this country,” Ms. Levenson said.

But often lost in the uproar, she said, was the blood bath that claimed the lives of two people.

Los Angeles has a way of striking the set and recreating itself every couple of decades, and the city where the Simpson trial played out can be hard to locate now. His mansion on North Rockingham Avenue is gone, lost to foreclosure and razed in 1998 after the Brown and Goldman families won a $33.5 million civil judgment against Mr. Simpson.

Many of those closely associated with his case have long since died or moved out of the spotlight. Johnnie Cochran, the charismatic defense lawyer who led Mr. Simpson’s legal “Dream Team,” died in 2005 from a brain tumor. Robert Kardashian, who stopped speaking to Mr. Simpson after the trial, and whose daughters and ex-wife went on to become reality TV moguls, died of esophageal cancer in 2003.

News of Mr. Simpson’s death rippled on Thursday throughout Los Angeles with residents reaching for half-forgotten memories.

Such was the case for Sandy Kinder, 72, and her husband, David Kinder, 87, who have lived in the Silver Lake neighborhood for about four decades.

The couple remembers being glued to the television, watching the slow chase and saying, “How is this going to end?”

“It was a very sad time,” Ms. Kinder said. “Very brutal.”

When out-of-town guests wanted to see where Mr. Goldman had lived, the Kinders drove to the apartment in Brentwood.

“And, of course,” Ms. Kinder said, “the police, you know, swarmed on us and told us to get out.”

Patrik-Ian Polk, 50, recalled his days as a recent transplant, attending film school at the University of Southern California, where Mr. Simpson was first propelled to national stardom and won a Heisman Trophy.

Mr. Polk arrived from Mississippi in 1992, weeks after riots broke out following the acquittal of police officers who were captured on video beating Rodney King. Mr. Polk filmed burned-out buildings in South Los Angeles for class projects.

“I mean, it was all this destruction, you know?” he recalled. “I was still a hopeful, young, aspiring artist, happy to be out of Mississippi and in a big city.”

Watching the police chase, among the earliest of those televised, had been shocking, but even more so had been learning that Mr. Simpson was inside.

“As a Black icon, obviously he was very important to the African American community,” said Mr. Polk, a filmmaker who is Black. “Now, we’re used to celebrities falling from their perches because of the advent of social media and technology,” he said. “It was one of the first times I remember something that infamous happening.”

Los Angeles, at the time, felt like a place in transition. The acquittal of white police officers in the King case and the subsequent riots still lingered on people’s minds, and many in the city experienced the Simpson trial through the lens of the racial reckoning that followed.

To some, Mr. Simpson’s acquittal seemed pure proof of the power of money; to others, the verdict, gained with the help of a Black defense lawyer, was an immense symbol of justice.

“The police were so bad on Black and Hispanic people that when he won, yeah, I was elated,” said Don Garrett, 65, an actor who has lived in Los Angeles for four decades. “It felt like a win for Black people.”

But Mr. Garrett was disappointed by what Mr. Simpson did after the criminal trial — writing a book hypothesizing how he might have pulled off the killings, and eventually being convicted of stealing sports memorabilia at gunpoint in 2007 with five other men, for which he was sentenced to a minimum of nine years in prison.

It is that coda that Mr. Garrett said prompted no emotional reaction from him on Mr. Simpson’s death, only a small wish: “I hope he finds peace.”

[ad_2]