[ad_1]

In The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Change, bell hooks warns that it isn’t true that men are unwilling to change; they are actually afraid to change.

“It is true that masses of men have not even begun to look at the ways that patriarchy keeps them from knowing themselves, from being in touch with their feelings, from loving,” hooks writes in the 2004 edition of the book. “To know love, men must be able to let go of the will to dominate. They must be able to choose life over death. They must be willing to change.”

In 2014, Charles Berry and Richie “Reseda” Edmond-Vargas put hooks’ words to the test by co-founding the Success Stories Program at the California Training Facility prison. The program is dedicated to treating some of the root causes of harm and violence—patriarchy and toxic masculinity—among people who are criminalized and incarcerated.

Also known as “The Feminist on Cellblock Y,” after being featured in a CNN documentary of the same name, Edmond-Vargas noticed an oversight in the programs offered to prisoners in California. Though there were instructional workshops on topics like anger management and substance abuse, none of the education on offer actually got to the heart of the problem: patriarchy.

“Most behavioral issues, they’re all steeped in patriarchy, but nobody was talking about it [in prison].” Mannie Thomas III, Coach and Growth Coordinator of Success Stories and a previous participant of the program, said. “Richie really saw that oversight—we know everybody’s bouncing around the idea of masculinity and patriarchy, and no one’s really talking about it.”

Edmond-Vargas took that oversight as an opportunity to speak about patriarchy at the gym, where he was laughed out of the room. He persisted, and through trial and error and conversation with Transformational Coach and Growth Coordinator Chris Johnson, came up with a method of sharing experiences in a conversational setting that started reaching incarcerated men and encouraging them to change.

“Once we started to share very real stories, what we’ve seen is people’s ability to relate to the topic, the topic became real, right?” Thomas explained. “When you’re talking to a group of cisgender men about how patriarchy informs their life, and how it may keep them from being the highest version of themselves, or how it’s harming their community—before we told our stories, they couldn’t really make the correlation.”

Success Stories became a 12-week program where men are encouraged to reassess how they live their lives, and discover how to live more fully through the rejection of patriarchal values and toxic masculinity. The participants of the program meet once a week for two hours at a time and go through myriad topics.

Through exchanging stories and experiences on what matters most in the lives of the participants, participants redefine what’s most important to them. After exploring the root causes of male violence, facilitators offer what they see as the remedy for patriarchy: integrity and relearning how to feel emotions.

“We realized that while participating in patriarchy, men as a whole don’t have complex language to express complex emotions because we don’t do it often,” Thomas said. “So we have a conversation about love and what it means, because we realize that most of us grew up with the definition of love that may not actually be that. And then we’ll talk about our belief system and how it influences our behavior.”

*

In many ways, Success Stories is deconstructing and reconstructing the ways marginalized men relate to the world and to the people in their lives. Edward Munsuer, who attended the program while incarcerated, says that he learned another way to be a man through the workshops.

“Most men focus on violence, money, and women, as well as repressing and covering up their true emotions,” Munsuer said. “The world makes us think that if we have the hottest girl, or the most money, or we are the toughest and punk people, or beat people up, then we are the coolest and everybody will like us. But when we treat people with love and equality, the world becomes a better place.”

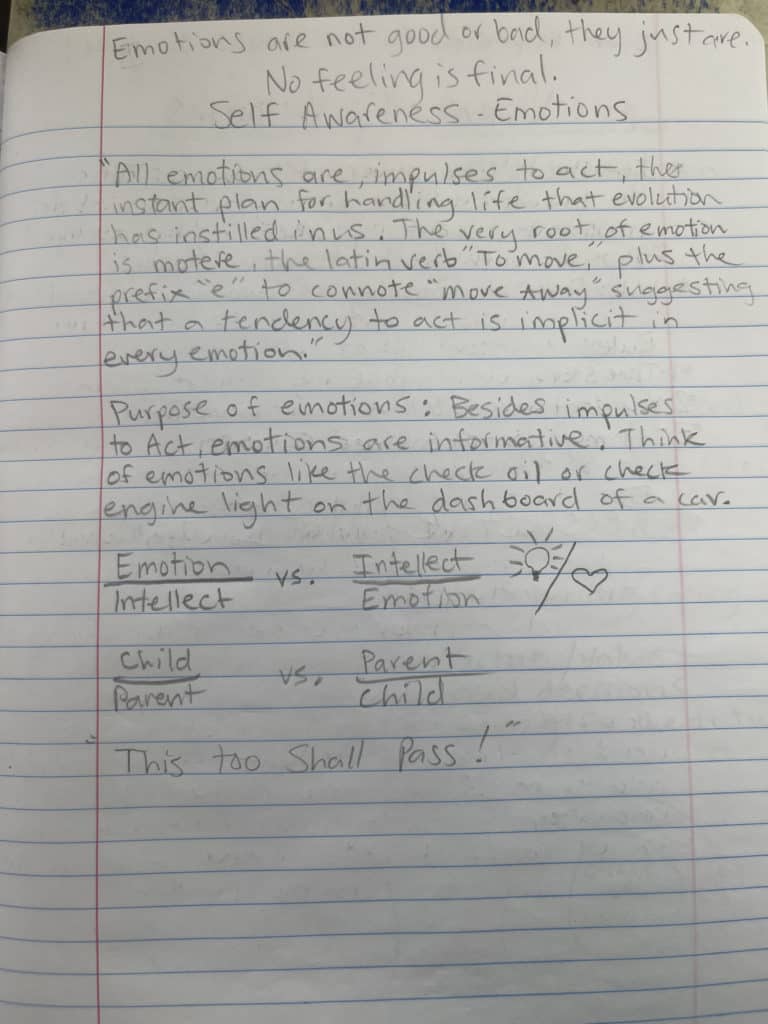

The program also powerfully teaches men how to love in healthy ways, recognizing that patriarchy and toxic masculinity might have hindered their ability to give and receive love. In a page of Munsuer’s notes during the program, he wrote down the “seven A’s of love” taught in the course: action, attention, acceptance, appreciation, affection, affirmations and actualization. Next to each word, Monsuer noted what made sense to him, and today he puts the lessons in practice.

“My experience with Success Stories was quite profound,” he said. “It truly opened my eyes to focus on what’s important in life, as well as love for others.”

The program also has a recommended list of books to accompany the conversations and learning experiences. All About Love, The Will to Change, and We Real Cool—all by bell hooks—are a few of the readings recommended to participants. According to Thomas, the reading is not a requirement but it can help men understand they are operating within a system of patriarchal capitalist exploitation.

“The thing that we’ve noticed about patriarchy and misogyny is that men feel like that we’re the only ones going through this,” Thomas said. “And a lot of us don’t even recognise that we’re working within a system. So when you have the opportunity to read the literature, it makes it more real, because it’s like—oh, this isn’t just me.”

The transformative power of the program is that it’s designed to reach all kinds of people from all kinds of backgrounds, and lead them to understand, together, that patriarchy and toxic masculinity have been imposed onto their lives from an early age. The collective discovery fosters a feeling of comradery and companionship that is the polar opposite of the isolation of patriarchy.

“We were all given this template about masculinity and because we are part of this patriarchal system, we’ve experienced a lot of the same things right,” Thomas said. “This opens up the door for people to be more truthful and vulnerable, because they’re seeing somebody who’s experienced the same thing. And it alleviates this isolation that we feel as men because, as men, we’re not told to help each other out. Some of the participants are doing that for the first time, it’s not comfortable for them, but it’s relieving and it’s healing.”

The program has faced resistance and challenges since its inception. Thomas himself says he was skeptical of Edmond-Vargas when they first met in the prison yard. Thomas made a comment about Edmond-Vargas tattoo being gay, and his response was so non-accusatory and open-ended that Thomas became intrigued.

“He was like: ‘Have you ever considered that the way that you use language perpetuates the oppression of other people?’ I was like, bro, you’re doing too much. And I was arrogant at the time. But then it was just eating at me, like, wait a minute, what am I missing? So I asked him about the group.”

The resistance Thomas described in himself, often held by some participants of the program, is overcome through the sharing of personal experiences with other men. This exchange exposes the similarities of the participants’ stories, and how patriarchy encouraged them to be violent to prove themselves as men.

From that point on, ignoring patriarchy as an active force in their lives becomes impossible, and so the work begins.

But the most impactful part of Success Stories, which has an abolitionist politic behind its work and scope, is that it’s helping men be released from prison early with a better perspective on how to live a full life. While Thomas doesn’t have data to share on the program’s success yet, he says most of the core members of the organization were sentenced to life in prison and got out early largely due to the program.

“We went from a program inside prison that nobody wanted to talk about to now a program that’s not only inside, but is being taught in multiple prisons,” Thomas said. “The prisons gave us rehabilitative achievement credits, which means people who go through our program actually earn time off their sentence. That was huge.”

Punishment and imprisonment, Thomas says, is not the solution for patriarchy and the harm caused by toxic masculinity — indeed, the current solutions we have for male violence generally result in recidivism and more harm instead of helping men of color find better ways to live in community. Still, he believes the program can be expanded beyond prison to prevent incarceration through educating boys before they offend.

“We hope to be the alternative to the punishment culture,” Thomas said. “Don’t send people to jail, send them to our program because we believe true transformation is possible while people are still in our community without having to subjugate them to further isolation.”

[ad_2]