[ad_1]

Watching the Alzheimer’s research world from the outside over the past two years has felt like a car ride over an unpaved mountain road without a seatbelt. In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration took the unusual step of overruling its advisory committee to approve the sale of Aduhelm, the first new Alzheimer’s drug in nearly two decades. The drug was designed to work by clearing accumulations of amyloid beta, a protein that has long been linked to the disease, from patient’s brains. In clinical trials, the drug did remove amyloid—but it didn’t convincingly improve cognition, so the committee recommended against it.

But the FDA determined that amyloid clearance was enough, and it gave Aduhelm accelerated approval. The decision was wildly controversial—it prompted internal and congressional investigations, and three members of the advisory committee resigned.

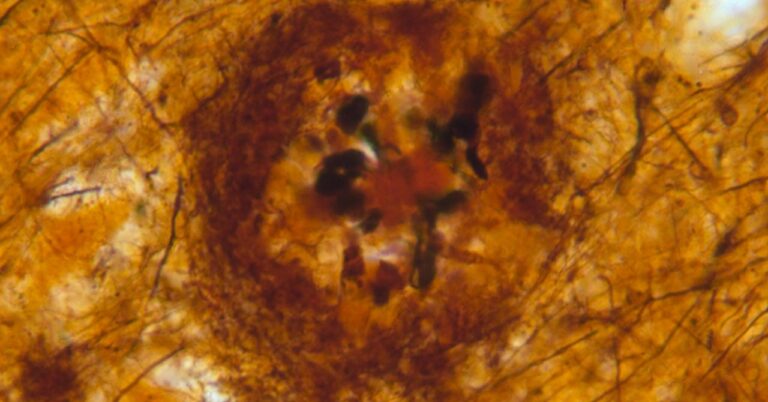

Suddenly, journalists across the country were scrambling to break down the “amyloid hypothesis” for their readers, in order to explain why the FDA would approve a drug without evidence that it reduced symptoms—and why that decision provoked so much debate. The story went like this: For decades, many scientists have believed that Alzheimer’s disease is caused by amyloid beta plaques, clumps of misfolded amyloid beta protein, possibly because these plaques are toxic to neurons. Dissenters have argued that the amyloid camp has long maintained a hegemonic hold on the field, forcing out alternative theories—despite the repeated failures of amyloid-targeting drugs, which, according to the amyloid hypothesis, should have worked. Then in 2022, Science outlined allegations against one amyloid researcher accused of serious and systematic dishonesty, reinforcing concerns that the amyloid hypothesis was a dubious proposition promulgated by fraudsters.

This September, the ride took another turn with the release of preliminary results from the Phase 3 trial of lecanemab. Like Aduhelm, lecanemab is an antibody that targets amyloid beta, and it was developed by the same companies. But this time, the drug did measurably slow cognitive decline in a clinical trial of almost 2,000 people with early-stage Alzheimer’s. In general, everyone’s cognition got worse over the course of the trial, but those who got the drug experienced less decline than those who received a placebo. The difference was small: After 18 months, patients on lecanemab saw only half a point less of decline on a standardized cognitive scale that operates in half-point increments.

After so much hemming and hawing about the amyloid hypothesis, this new drug would seem to have proved it—lecanemab cleared amyloid beta from people’s brains, and the progression of their disease slowed. In the research world, though, the story hasn’t been nearly so black-and-white. After years of failed drugs, Alzheimer’s scientists are excited that something might finally have worked, if only modestly. But the implications of the trial are complicated—partly because the amyloid hypothesis itself isn’t nearly as straightforward as it may seem.

“By and large, people would say amyloid is important. I don’t think anyone is saying that amyloid isn’t important,” says Eleanor Drummond, Bluesand senior research fellow at the University of Sydney. The question, she says, is “whether it’s the be-all and end-all”—enough to justify a drug approval with little other evidence of benefit, and enough to dominate the search for a cure for Alzheimer’s.

[ad_2]