[ad_1]

“If you have not seen a mighty Geminid fireball arcing gracefully across an expanse of sky, then you have not seen a meteor.”

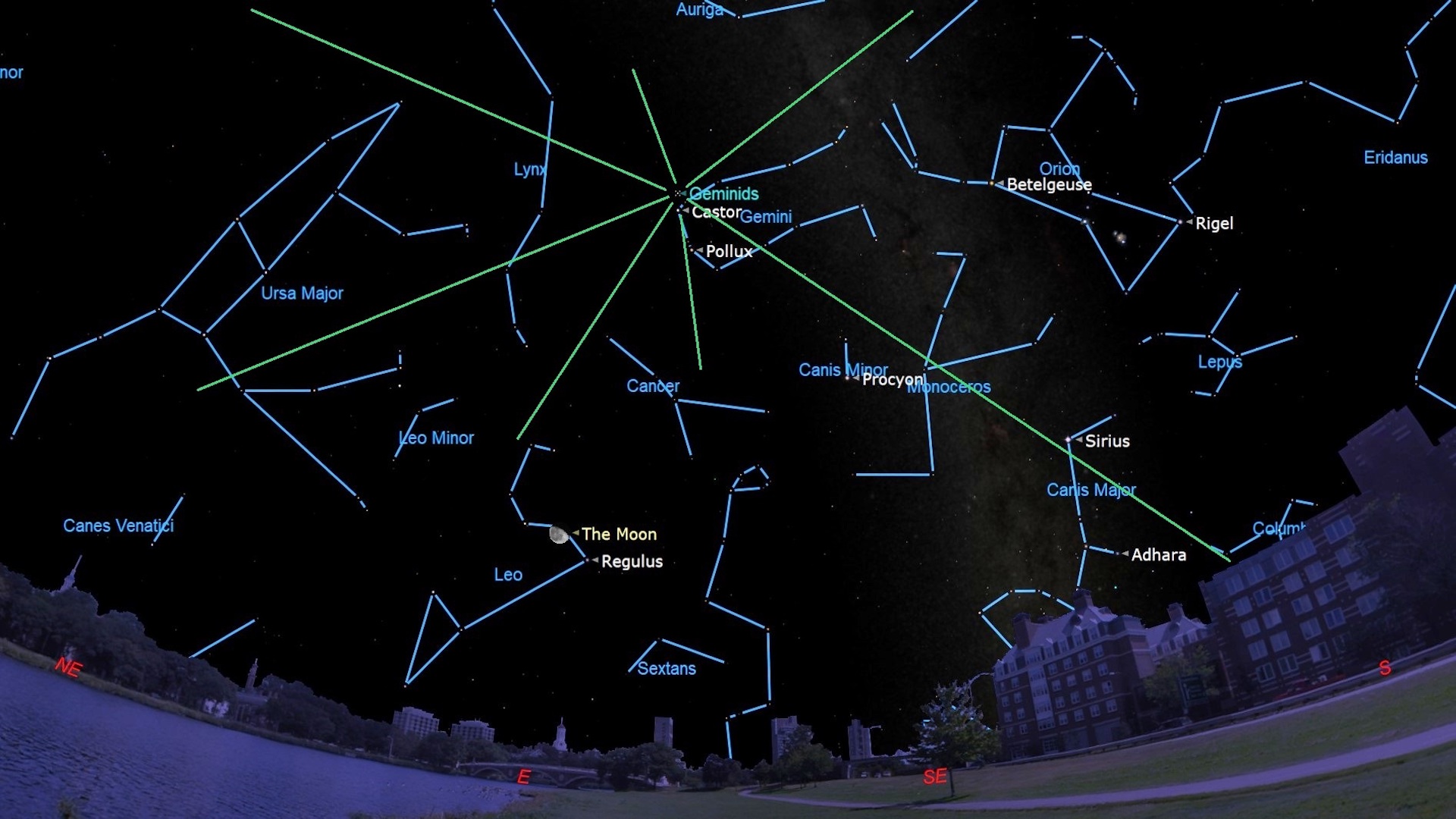

So, note astronomers David Levy and Stephen Edberg when writing of the annual Geminid meteor shower, which is predicted to reach its peak before dawn next Wednesday morning (Dec. 14). Unfortunately, as was the case this year with its summertime counterpart, the August Perseids, this year’s December Geminids will be seriously hindered by bright moonlight.

A bright (70% illuminated) waning gibbous moon in the Leo constellation will have already come over the east-northeast horizon by around 9:30 p.m. local time on Tuesday evening (Dec. 13) and will light up the sky through the rest of the overnight hours. This is particularly unfortunate, since the Geminids are now ranked as the very best of the annual meteor displays presently visible from Earth.

Related: Meteor showers 2022: Where, when and how to see them (opens in new tab)

Joe Rao is a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium.

The Geminid meteors are — for those willing to brave the chill of a December night — an excellent late-autumn shower and usually the most satisfying of all the annual showers, even surpassing the Perseids. Studies of past displays show that this shower has a reputation for being rich both in slow, bright, graceful meteors and fireballs as well as faint meteors, with relatively fewer objects of medium brightness. Many appear yellowish in hue. Some even seem to form jagged or divided paths.

Because Geminid meteoroids are several times denser than the cometary dust flakes that supply most meteor showers, and because of their relatively slow speed with which they encounter Earth (22 miles (35 km) per second), these December meteors appear to linger a bit longer in view than most. Moving at roughly half the speed of a Perseid or Leonid, a Geminid fireball can be quite spectacular and dazzling enough to attract attention even in bright moonlight.

Slow start, fast finish

The Earth moves quickly through this meteor stream producing a somewhat broad, lopsided activity profile. Hourly rates started to increase very slowly from this past Sunday (Dec. 4), and by this Sunday night (Dec. 11) they will be appearing at roughly one quarter of their normal peak strength. Were it not for the moon‘s interference late Tuesday night (Dec. 13) into Wednesday morning (Dec. 14), a single observer under a dark non-light-polluted sky might average as many as one or two meteor sightings per minute (60 to 120 per hour).

After Tuesday night, these high rates are expected to drop off more sharply; down to only a quarter of their peak strength again the very next night.

But there is good reason to keep watching for Geminids even after their peak has passed, for those “late” Geminids, tend to be especially bright. Renegade late stragglers might still be seen up until about Saturday (Dec. 17). After that, the Geminids are gone until next year.

Where and when to watch

These bright, medium speed meteors appear to emanate from near the bright star Castor, in the constellation of Gemini, the Twins, hence the name “Geminid.” The track of each meteor does not necessarily begin near Castor, nor even in the constellation Gemini, but it always turns out that the path of a Geminid, if extended backward along the direction of flight, passes through a tiny region of sky about 0.2-degree in diameter (an effect of perspective). In apparent size, that’s less than half the width of the moon as seen from Earth’s surface. As such, this is a rather sharply defined radiant, as meteor showers go, suggesting the stream is “young” — perhaps only several thousand years old.

Generally speaking, depending on your location, Castor begins to come up above the east-northeast horizon right around the time evening twilight is coming to an end. So, the best advice is to be outside from then until moonrise if you can, and you may catch sight of a few Geminids while the sky is still dark and moonless.

Also, as Gemini is beginning to climb the eastern sky just after darkness falls, there is a fair chance of catching sight of some “Earth-grazing” meteors. Earthgrazers are long, bright shooting stars that streak overhead from a point near to even just below the horizon. Such meteors are so distinctive because they follow long paths nearly parallel to Earth’s atmosphere.

With all this as a background, it becomes obvious that the best time to look for Geminids this year will be during early-to-mid evening hours. In fact, Tuesday (Dec. 13) and Wednesday (Dec. 14) will provide us with two “windows” of dark skies spanning the time between the end of evening twilight and the rising of the moon. Generally speaking, there will be nearly 3 and a half hours of completely dark skies available on Tuesday (Dec. 13) evening, increasing to almost 4 and a half hours on Wednesday (Dec. 14).

The table below has viewing times and dark sky windows for some selected cities. All times are local standard times. “Twilight ends” is when astronomical twilight ends — when there is no longer any discernable horizon glow over the southwest horizon. “Viewing window” is the number of minutes between the time of moonset and the end of twilight. (For example: When will the sky be dark and moonless for Geminid viewing on Tuesday evening from Washington? Answer: there will be a 201-minute period of dark skies beginning at the end of evening twilight (6:22 p.m.) and continuing until moonrise (9:43 p.m.).)

| Location | Twilight ends (Dec. 13) | Moonrise (Dec. 13) | Viewing window (Dec. 13) | Twilight ends (Dec. 14) | Moonrise (Dec. 14) | Viewing window (Dec. 14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 5:53 p.m. | 9:10 p.m. | 197 min. | 5:53 p.m. | 10:13 p.m. | 260 min. |

| Wash. DC | 6:22 p.m. | 9:43 p.m. | 201 min. | 6:22 p.m. | 10:44 p.m. | 262 min. |

| Miami | 6:53 p.m. | 10:21 p.m. | 208 min. | 6:53 p.m. | 11:14 p.m. | 261 min. |

| Chicago | 6:00 p.m. | 9:21 p.m. | 201 min. | 6:00 p.m. | 10:23 p.m. | 263 min. |

| St. Louis | 6:15 p.m. | 9:39 p.m. | 204 min. | 6:15 p.m. | 10:39 p.m. | 264 min. |

| Houston | 6:48 p.m. | 10:17 p.m. | 209 min. | 6:48 p.m. | 11:12 p.m. | 264 min. |

| Denver | 6:12 p.m. | 9:38 p.m. | 206 min. | 6:13 p.m. | 10:39 p.m. | 266 min. |

| Helena | 6:30 p.m. | 9:50 p.m. | 200 min. | 6:31 p.m. | 10:57 p.m. | 266 min. |

| Phoenix | 6:58 p.m. | 10:20 p.m. | 202 min. | 6:58 p.m. | 11:17 p.m. | 259 min. |

| Seattle | 6:10 p.m. | 9:31 p.m. | 201 min. | 6:10 p.m. | 10:38 p.m. | 268 min. |

| San Diego | 6:11 p.m. | 9:43 p.m. | 212 min. | 6:12 p.m. | 10:39 p.m. | 267 min. |

| Oakland | 6:25 p.m. | 9:54 p.m. | 209 min. | 6:25 p.m. | 10:54 p.m. | 269 min. |

Don’t forget to bundle up!

But keep this in mind: at this time of year, meteor watching can be a long, cold business. You wait and you wait for meteors to appear. When they don’t appear right away, and if you’re cold and uncomfortable, you’re not going to be looking for meteors for very long! Therefore, make sure you’re warm and comfortable. Warm cocoa, coffee or tea can take the edge off the chill, as well as provide a slight stimulus. It’s even better if you can observe with friends. That way, you can cover more sky. Give your eyes time to adapt to the dark before starting.

A final point to note is that Geminids stand apart from the other meteor showers in that they seem to have been spawned not by a comet, but by 3200 Phaethon, an Earth-crossing asteroid. (Maybe we could say that the Geminids are truly “rock” stars?)

Then again, the Geminids may be comet debris after all, for some astronomers consider Phaeton to actually be the dead nucleus of a burned-out comet that somehow got trapped into an unusually tight orbit.

Happy meteor hunting!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium (opens in new tab). He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine (opens in new tab), the Farmers’ Almanac (opens in new tab) and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) and on Facebook (opens in new tab).

[ad_2]