[ad_1]

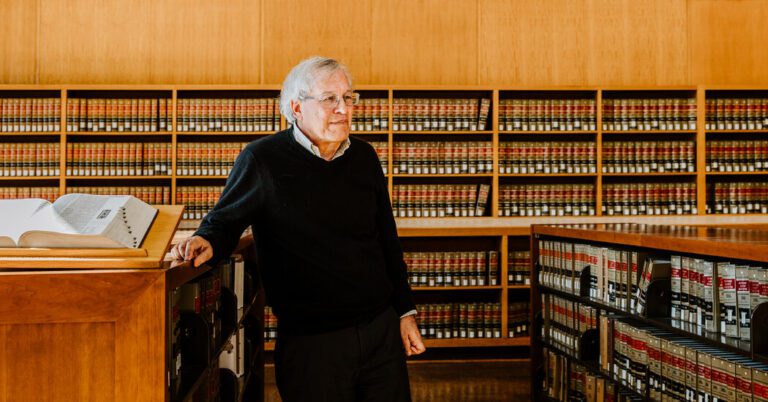

The dean of Berkeley’s law school is known as a staunch supporter of free speech, but things became personal for him when pro-Palestinian students disrupted a celebratory dinner party for some 60 students at his home.

Erwin Chemerinsky, the law school dean, hosted the dinner on Tuesday night in the backyard of his Oakland, Calif., home. The party was supposed to be a community building event, open to all third-year law students, with no speeches or formal activities.

But a third-year law student and a Palestinian activist, Malak Afaneh, stood up at the event, holding a microphone, and launched into a speech.

As she began to talk, Mr. Chemerinsky, a noted Constitutional scholar, can be seen shouting, “Please leave our house! You are guests in our house!”

Catherine Fisk, another Berkeley law professor and Mr. Chemerinsky’s wife, can be seen with her arm around Ms. Afaneh, trying to yank the microphone away and pulling the student up a couple steps.

Ms. Afaneh and other student protesters described Ms. Fisk’s struggle for the microphone as a disproportionate and violent response. Students, they said, had a right to speak at a university gathering.

Mr. Chemerinsky said the dinner was paid for by the university. But he said that the students, who brought their own microphone and amp, had no such free speech rights in a private home, at a dinner with no planned remarks.

In the past, Mr. Chemerinsky has supported speech rights for pro-Palestinian students, including the right to block Zionists from speaking to their groups. But this latest incident shows how the Israel-Hamas war has intensified and complicated the free speech debate. As pro-Palestinian students stage sit-ins and disrupt events at campuses across the country, some administrators, pressed by donors and politicians, have cracked down on unruly behavior, arresting and suspending students.

The moment has been especially fraught for the University of California, Berkeley, long a hotbed of leftist activism and the home of the ’60s Free Speech movement. As protests there continue over the Middle East conflict, some Jewish students and alumni have criticized university officials, saying that the school has tolerated activism that veers into antisemitic speech.

On Thursday night, about 15 protesters returned to Mr. Chemerinsky’s home for another student dinner, this time staying outside the house for about 90 minutes, Mr. Chemerinsky said.

“They were carrying signs and had drums,” he wrote in an email message. “They stood in front of our house chanting (some quite offensive) and banging their drums.”

In February, an event at Berkeley featuring an Israeli speaker was canceled after a crowd of protesters broke down doors, which the chancellor, Carol Christ, said was “an attack on the fundamental values of the university.” Last month, Representative Virginia Foxx, chair of the House committee on education that has been investigating antisemitism on campus, sent a letter to university officials demanding documents and information about Berkeley’s response to antisemitism.

Mr. Chemerinsky said that he himself was the subject of an antisemitic flier, circulated earlier in the week, which depicted a cartoon image of him gripping a bloody knife and fork, with the words “No Dinner With Zionist Chem While Gaza Starves.”

“I never thought I would see such blatant antisemitism,” he wrote in a statement to the law school community after the first protest, “with an image that invokes the horrible antisemitic trope of blood libel and that attacks me for no apparent reason other than I am Jewish.”

The Berkeley chapter of Law Students for Justice in Palestine, where Ms. Afaneh is co-president, did not respond to requests for an interview. But Camilo Pérez-Bustillo, the head of the local chapter of the National Lawyers Guild, which consulted with Ms. Afaneh before the protest, said that Mr. Chemerinsky was not singled out because he is Jewish.

“He was being targeted because he’s failed to take a public position on a matter of urgency,” Mr. Pérez-Bustillo said, “which is U.S. complicity with the unfolding genocide.”

The Chemerinsky dinner on Tuesday fell on the last day of Ramadan, the Muslim holy month. As Ms. Afaneh and Professor Fisk both gripped the microphone, Ms. Afaneh said, “We refuse to break our fast on the blood of Palestinian people” and accused the university system of sending billions of dollars to weapons manufacturers.

“I have nothing to do with what the U.C. does,” Ms. Fisk said. “This is my home.”

Ms. Fisk threatened to call the police but did not. After she let go of the microphone, Ms. Afaneh and about 10 other law students left peacefully and the dinner continued, Mr. Chemerinsky said.

“I am enormously sad that we have students who are so rude as to come into my home, in my backyard, and use this social occasion for their political agenda,” Mr. Chemerinsky wrote. Through Mr. Chemerinsky, Ms. Fisk declined to be interviewed.

Many pro-Palestinian supporters argue this is not the moment for decorum, as the death toll of Israel’s bombing in Gaza tops 30,000, according to Gaza health officials. The protesting students wanted Mr. Chemerinsky, who describes himself as a Zionist, to denounce what they described as an unfolding genocide and to call for the university to divest from companies that aid Israel’s military campaign.

After the dinner altercation, the Law Students for Justice in Palestine chapter demanded the resignations of Mr. Chemerinsky and Ms. Fisk, and called for a Palestine studies program that centers on the “resistance and the right to return in a settler-colonial context.”

Richard Leib, the board chairman of the University of California system, and Ms. Christ, the Berkeley chancellor, have supported the couple.

“I am appalled and deeply disturbed by what occurred at Dean Chemerinsky’s home last night,” Ms. Christ said in a statement on Wednesday. “While our support for Free Speech is unwavering, we cannot condone using a social occasion at a person’s private residence as a platform for protest.”

Mr. Chemerinsky said he invites first-year law students to a welcome dinner in his backyard to create a sense of community. This dinner — spread over three nights with about 60 students each — was for third-year students whose traditional welcome dinner was canceled because of Covid, Mr. Chemerinsky said.

The dean said he was such a believer in the tradition that when he bought a home in 2017, he made sure the backyard could fit a crowd.

“I never could have imagined this would be divisive or a flashpoint,” he said, adding, “It’s an ugly moment.”

[ad_2]