[ad_1]

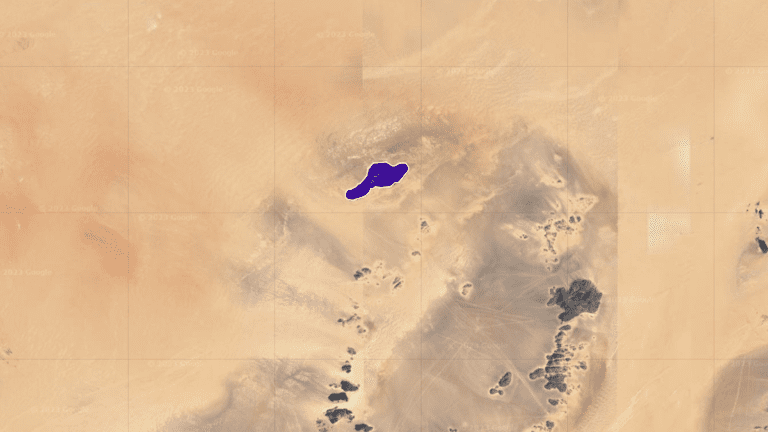

The more we learn about our climate, the better equipped we become in addressing the factors harming it. So, in July 2022, NASA’s Earth Surface Mineral Dust Source Investigation (EMIT) instrument was launched to map 10 key minerals in some of the world’s most arid regions, and how lofted dust in those areas affects our climate.

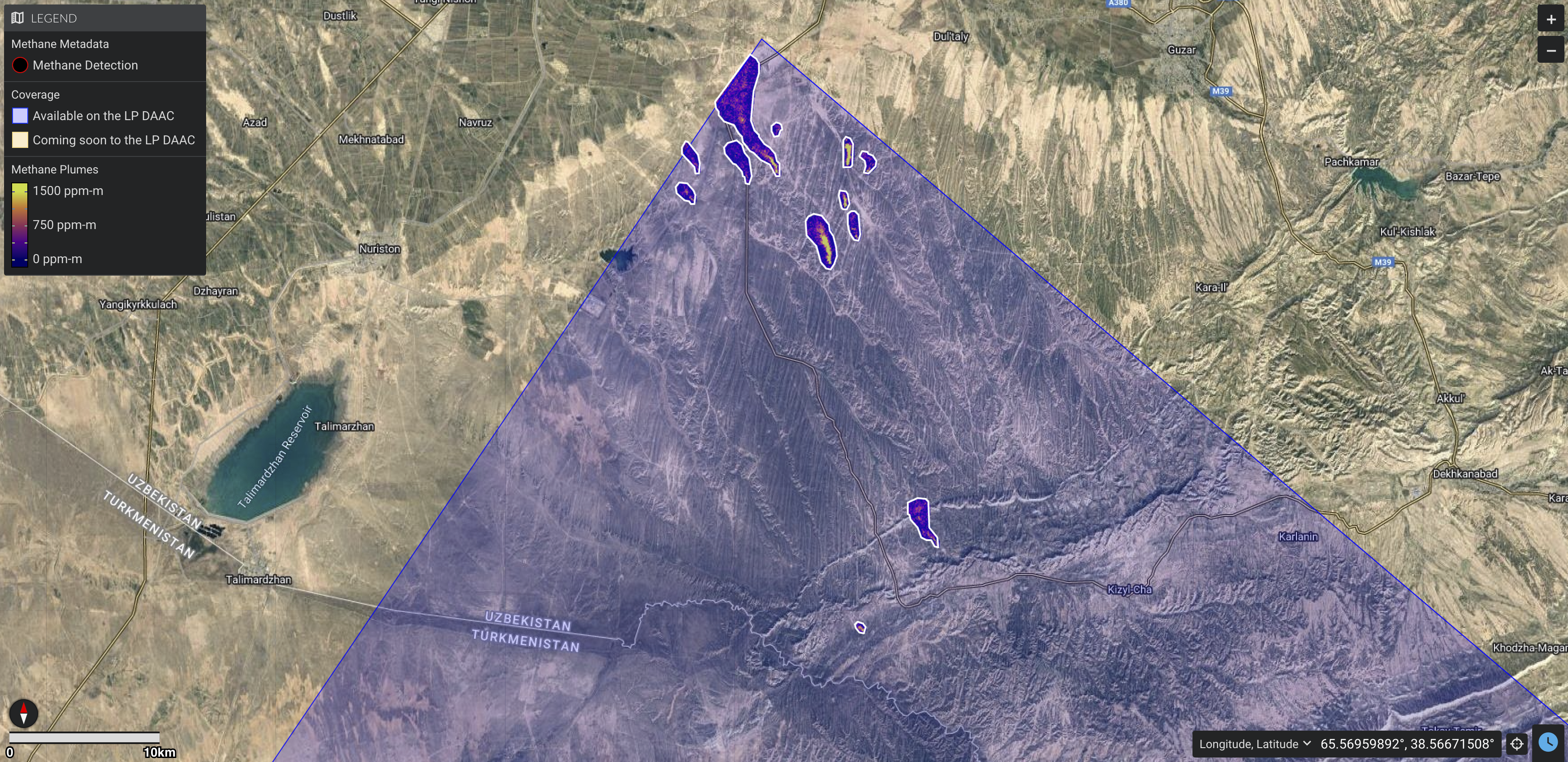

However, in brand new research, data from the instrument has been used to identify over 750 point-source emissions of greenhouse gases, including sources of methane from landfills, agricultural sites, and oil and gas facilities.

While the detection of greenhouse gases like methane was not part of EMIT’s primary mission, the imaging spectrometer on board the International Space Station (ISS) has proven to have such capacity. “We were a little cautious at first about what we could do with the instrument,” Andrew Thorpe, the paper’s lead author, said in a statement.

“It has exceeded our expectations,” he added.

Related: NASA searches for climate solutions as global temperatures reach record highs

Of the 750 sources of methane, EMIT was able to identify both large sources (emitting tens of thousands of pounds of methane per hour) and small sources (emitting hundreds of pounds of methane per hour). This is important because it provides accurate data on “super-emitters,” or sources of methane that produce a disproportionate share of emissions.

Methane is a particularly effective — in a bad way — greenhouse gas. It is up to 80 times more powerful at trapping heat than carbon dioxide is. So, being able to identify its sources can ultimately help scientists develop strategies to limit damaging emissions, as these emissions are, more often than not, human-driven. They’re also directly responsible for the climate crisis.

Typically, methane-detecting instruments are sent up in aircraft. From a lower altitude (about several thousand feet), these instruments tend to be more sensitive to sources of methane than EMIT — but such flights can only cover a limited area for a short time. These missions are also often considered too remote, too risky or too costly. Sometimes a combination of the three.

However, from 250 miles (402 kilometers) above our planet on the ISS, in its first 30 days of detection, EMIT managed to observe 60% to 80% of the methane plumes typically observed in those airborne campaigns. EMIT’s imaging spectrometer takes 50-mile-by-50-mile (80-km-by-80-km) images of the planet’s surface. Researchers call these “scenes.” Many scenes include regions well beyond the reach of typical methane detecting aircraft in general.

While NASA’s missions often focus on looking outward into the cosmos, EMIT proves it’s also important to look back at ourselves.

The study was published on Nov. 17 in the journal Science Advances.

[ad_2]