[ad_1]

A newly found black hole is shattering records, revealing new things about how such objects formed.

Two space telescopes paired up to examine a giant black hole that has a mass approximately equal to the galaxy that hosts it. It’s an early starter: the galaxy existed just 470 million years after the Big Bang that formed our universe about 13.8 billion years ago. The existence of this black hole is, therefore, a huge clue as to how supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies form.

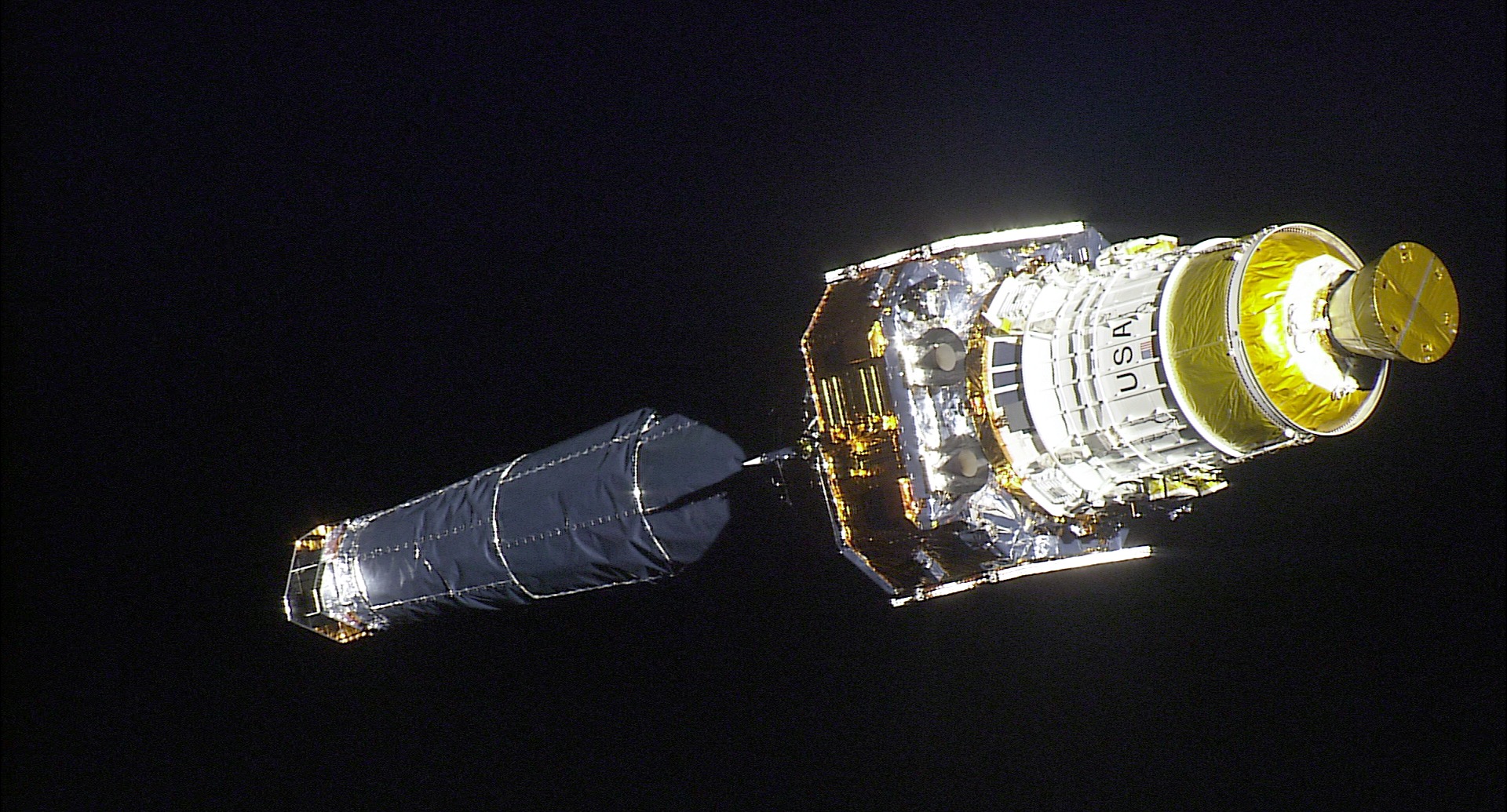

Black holes are very dense objects with such intense gravity that even light cannot escape, if it strays too close. The new black hole is a record breaker: the most distant yet observed in X-rays. As such, the observations from NASA‘s James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST) and the agency’s Chandra X-ray Observatory capture the black hole in a stage of its growth never before seen.

Related: Black holes: Everything you need to know

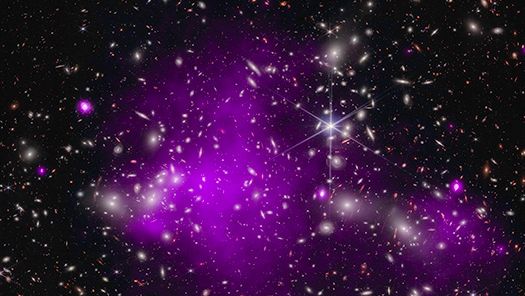

The JWST first spotted the feeble light of the early galaxy, called UHZ1. The mass of the galaxy is approximately 140 million times the mass of the sun. JWST saw the galaxy due to gravitational lensing, when the gravity of a massive foreground galaxy cluster, Abell 2744, amplified the light of UHZ1.

When Chandra followed up on UHZ1 and observed it for two weeks, it detected powerful X-rays coming from a disk of gas swirling around in the gravitational field of a supermassive black hole at the core of the distant galaxy.

“We needed Webb to find this remarkably distant galaxy, and Chandra to find its supermassive black hole,” Ákos Bogdán of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement Monday (Nov. 6). Bogdán is the lead author of a paper in Nature Astronomy describing the X-ray observations and signature of the black hole, mainly based on Chandra but also including Webb data.

Judging by the brightness and intensity of the X-rays, which are connected to the strength of the black hole’s gravity, the black hole has a mass of the order of tens of millions to hundreds of millions of solar masses, equivalent to the mass of its host galaxy.

Related: Star-birthing galaxies can hide supermassive black holes behind walls of dust

UHZ1 is still fairly small for a galaxy, however. Models of galaxy formation describe how they begin small and then grow through mergers, either with other galaxies or gigantic intergalactic gas clouds. What isn’t understood very well is how their supermassive black holes form.

There are two candidate theories to explain their formation. One is that they formed through rapid mergers of stellar-mass black holes produced by exploding stars. The other possibility is that supermassive black holes formed directly from a collapsing gas cloud that had a mass between 10,000 and 100,000 times that of the sun.

The new research suggests the newfound black hole was born large, with an estimated mass of roughly 10 million and 100 million suns when calculating the X-rays’ brightness and energy.

“There are physical limits on how quickly black holes can grow once they’ve formed, but ones that are born more massive have a head start. It’s like planting a sapling, which takes less time to grow into a full-size tree than if you started with only a seed,” said Andy Goulding of Princeton University. Goulding is lead author of a Sept. 22 paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters that reports the galaxy’s distance and mass, and co-author on the new Nature Astronomy paper.

The brightness and energy of the X-rays are in the realm predicted in calculations by theoretical astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan of Yale University, which lead to the creation of “outsize black holes” that form directly from gas cloud collapse.

“We think that this is the first detection of an outsize black hole, and the best evidence yet obtained that some black holes form from massive clouds of gas,” Natarajan said in the same statement. “For the first time, we are seeing a brief stage where a supermassive black hole weighs about as much as the stars in its galaxy, before it falls behind.”

In most modern galaxies, the supermassive black hole amounts to only a tenth of the mass of its host galaxy. The mass of the black hole is also correlated to the stellar mass of a spiral galaxy‘s central bulge, or the overall mass of an elliptical galaxy. By witnessing an active black hole in this stage of growth, the observations could shed light on how this correlation occurs. Either way, UHZ1 certainly has a lot of growing to do to outpace the growth of its black hole.

[ad_2]