[ad_1]

The Galápagos Islands are famed as a bizarre menagerie of blue-footed boobies, giant tortoises and seafaring iguanas. But the waters surrounding the archipelago are also brimming with biodiversity, including nearly 3,000 species ranging from pint-size penguins to colossal whale sharks.

And now researchers have discovered yet another trove of life’s diversity in the Galápagos, this one in a dark, frigid world more than 400 meters below the waves. The team used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to map two pristine cold-water coral reefs—one of which is the size of eight football fields—and two submerged volcanoes, or seamounts, in high resolution. These abyssal reefs, which may be thousands of years old, are teeming with sharks, squid and a variety of other creatures.

The new discovery provides a detailed glimpse of the region’s overlooked assortment of cold-water corals, says Katleen Robert, a researcher specializing in seafloor mapping at the Fisheries and Marine Institute of Memorial University of Newfoundland. Robert led an international team of collaborators aboard the nonprofit Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor (too) during the 30-day mapping expedition, which began in September. (Previous expeditions on the vessel have recorded baby octopuses hatching in a surprise deep-sea nursery and a strange ecosystem under the seafloor.)

The reefs and seamounts lie within the Galápagos Marine Reserve (GMR), a swath of the eastern Pacific Ocean spanning some 133,000 square kilometers. The area, about 1,000 kilometers west of Ecuador, sits at the intersection of three major ocean currents; the resulting influx of drifting life forms and nutrients has helped it develop one of the planet’s most biodiverse marine habitats.

Very little was known about the ecosystems in the GMR’s deeper reaches, so one of the team’s main goals was to chart their layout. According to Robert, most deep-sea mapping uses acoustic methods because sound spreads more easily through water than light does from far distances. But at closer ranges, measuring with laser beams instead of sound waves creates a much higher-resolution map of the seafloor’s rugged topography. So the team deployed the ROV SuBastian to get close enough to bounce lasers off of the two reefs, located between 370 and 420 meters below the surface.

As SuBastian explored the reefs, the researchers used the cutting-edge laser scanning technology to craft maps of this hidden environment with a resolution of down to two millimeters. The maps were so detailed that the scientists aboard the research vessel could pinpoint individual animals and make out minute details of the corals’ anatomy.

When the researchers return to the site in the future, Robert says, they could even use this mapping technique to measure the corals’ elusive growth rates. “Cold-water corals grow very slowly, like a few millimeters a year over hundreds of years,” she says. “If you want to see the corals grow, you really have to be able to have that really high resolution that our laser scanner is able to provide.”

.jpg)

The vast sizes of these reefs—one covers a whopping 800-meter-long stretch of the seafloor, while the other spans more than 250 meters—led the researchers to posit that corals have been living here for hundreds, and possibly thousands, of years.

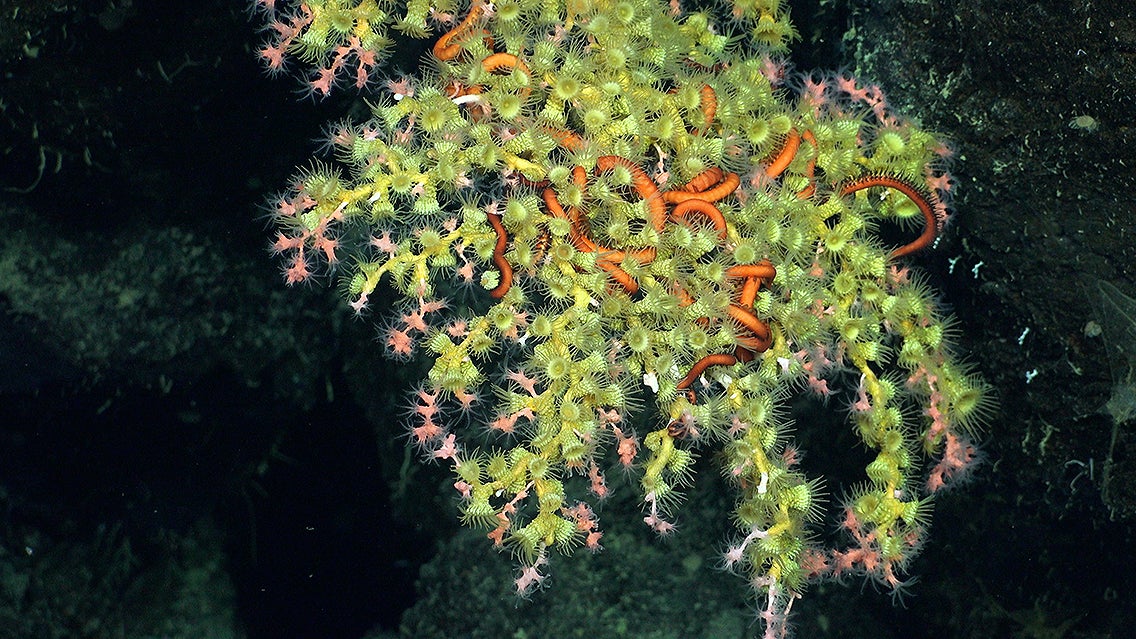

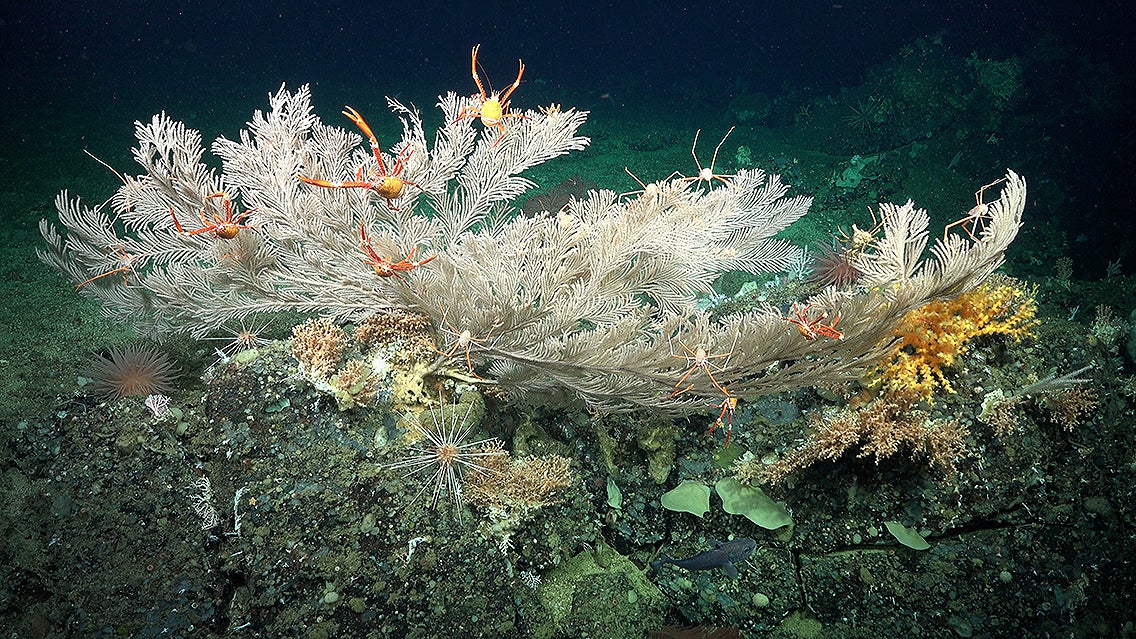

Unlike the better-known shallow coral reefs that thrive in balmy, sunlit waters, cold-water corals thrive hundreds to thousands of meters beneath the surface—often in frigid waters with little to no light. Instead of relying on photosynthetic algae for energy, the polyps of these corals catch tiny organisms floating in the water. This allows them to build lush coral gardens that act like an oasis in the dark.

As the team mapped the reefs, it identified more than 40 different varieties of cold-water corals, some of which were covered with eggs. The corals were also crawling with critters, including squat lobsters, feathery brittle stars, and dense patches of anemones and sponges. Several species of fish patrolled the reefs, including skates, sharks and ratfish, whose large, emerald-green eyes gather the scant light available in these inky depths. The scientists also found a variety of animals swimming above the reefs, including strawberry squid, whose mismatched eyes help them simultaneously search for prey above and below them.

As SuBastian collected samples of these deep-sea denizens, scientists aboard the Falkor (too) measured the area’s currents and water conditions. The two new reefs both occupy a layer of the water column with a low concentration of oxygen. Robert says future work is needed to determine why deep-sea corals cluster in such areas.

She believes the discovery of the new reefs is a major step in understanding and protecting these little-known seafloor environments throughout the eastern Pacific. Though the GMR reefs are protected, other similar ecosystems may be threatened by activities such as deep-sea mining. As Robert puts it, “We need to know that these reefs are there before we can realize what we can lose.”

[ad_2]