[ad_1]

The brain has a remarkable ability to adapt in response to injury. Healthy regions can take over functions that the damaged parts used to perform. “We’re trying to promote conditions in the surviving areas of the cortex that are more favorable to functional reorganization,” says Kenneth Baker, a neuroscientist at the Cleveland Clinic and an author on the paper.

A stroke diminishes the excitability of neurons—essentially, their ability to send signals and make connections to other parts of the body. In people who spontaneously recover from stroke, the excitability of those neurons rebounds. With the stimulation, Baker’s team was aiming to increase the excitability of the neurons near the damaged area and boost their ability to form new connections.

In the Cleveland Clinic study, the 12 patients all experienced strokes in the cerebral cortex—the outermost layer of the brain. Previous studies tried to directly stimulate this area, to no avail. The Cleveland team instead targeted a part of the cerebellum—located at the back of the head—called the dentate nucleus, a cluster of neurons involved in fine-control of voluntary movements and sensory functions. This area makes connections to other brain regions, including the cortex.

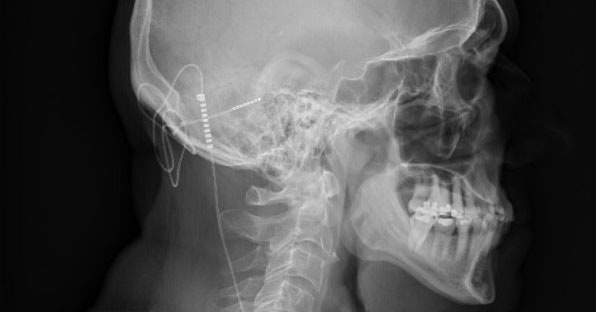

Surgeons implanted an electrode in each patient’s brain, along with a device under the skin of the chest that emits the electrical impulses. After a period of recovery from the surgery, patients went through two months of physical therapy. Then, researchers turned on the electrical stimulation and left it on for four to eight months while the participants continued physical therapy.

Researchers measured each person’s progress by administering a common test that assesses hand and arm function following stroke. Physical therapy alone led to modest gains of around three points on a 66-point scale. After the stimulation was turned on, median improvement jumped another seven points.

Participants also got better at carrying out everyday tasks such as using a comb, picking up a cup, and turning on a light switch. “Their motion and movement is not at the level of normal, but even the ability to use their hand at a higher rate than they were makes a big difference,” Baker says. The three patients who didn’t see meaningful improvements started off with worse deficits than the others.

Nicholas began to notice a difference after a few months with the stimulation on. He was able to lift his arm above his head and close his left hand, neither of which he could do before getting the implant. It’s made doing yard work and chores around the house easier. “I’m happy that it’s benefited me,” he says.

Researchers removed the devices once the study concluded, yet remarkably, the benefits lasted throughout the entirety of the 10-month follow-up period, suggesting that DBS might not need to be used permanently, as it is for Parkinson’s.

Courtesy of Cleveland Clinic

[ad_2]