[ad_1]

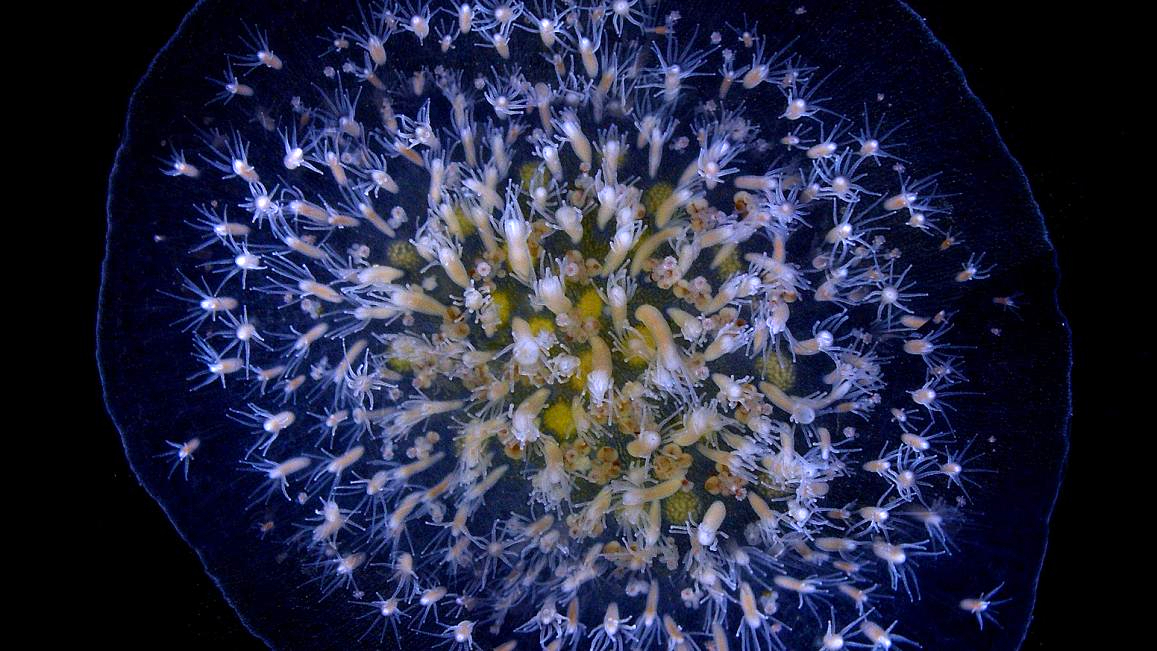

Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus, a small tube-shaped animal that grows on the shells of hermit crabs, is a wonder of regeneration. Cut off its head and mouth, and it grows new ones. Cut off its body, and it regrows that, too.

How does it accomplish such feats? A new paper provides a rough outline and comes to a surprising conclusion, that the cellular aging process, known as senescence, plays a pivotal role by working in reverse. What’s more, the paper says that while the aging process first evolved to serve bodily regeneration, it later became damaging when animals such as ourselves became vastly more complex.

What Is Senescence?

When a cell becomes stressed or damaged, or has simply grown old, it may enter a period of senescence – a downward spiral. This process limits the cell’s normal functioning and causes it to release a chemical cocktail that affects the surrounding cells. Inflammation, senescence and malignancy spread throughout the surrounding tissue.

This sounds detrimental. But the new paper found that senescence is pivotal to triggering regeneration in H. symbiolongicarpus.

Why Do Tubes Regenerate?

Past research has found that in most cases, the small animal relies on stem cells stored in its lower body to regenerate. So the new study sliced off just the upper mouth and set it aside to see if it would recover on its own.

When the tube regrew to its original size, the researchers checked to see what role senescence had played in creating new stem cells.

They found a surprising correlation. Turning off a key senescence gene also turned off the production of stem cells and tissue regeneration. Senescent cells no longer programmed other cells to become stem cells.

Diagram showing the anatomy of Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus. (Credit: Darryl Leja/National Human Genome Research Institute)

Living Forever

This ability to regrow and harness the process of aging makes the little animals practically ageless. It also calls into question the role of senescence and why more complex species suffer so greatly from its effects. Humans last shared a common ancestor with H. symbiolongicarpus some 600 million years ago, and since then, our senescence process seems to have only gotten worse.

“Typically, in humans, senescent cells stay senescent, and these cells cause chronic inflammation and induce aging in adjacent cells,” said Andy Baxevanis, a senior scientist at the National Human Genome Research Institute, in a statement. “Most studies on senescence are related to chronic inflammation, cancer and age-related diseases.”

Harnessing Instability

The key to regeneration may not be what the organism can create but what it can get rid of. The tube-shaped animals can shed unneeded senescent and stem cells, making it safer for them to undergo changes.

Mammals, on the other hand, rely on many complex structures and can’t afford to play fast and loose with their cellular structures. That may be why we can’t grow a new kidney or limb.

Still, our new understanding of senescence could offer insight into how our bodies work.

“Studies like this that explore the biology of unusual organisms reveal both how universal many biological processes are,” said Charles Rotimi, director of the Intramural Research Program at the National Human Genome Research Institute, in a statement. “Such findings have great potential for providing novel insights into human biology.”

Read More: Life After Death? Cryonicists Try To Defy Mortality By Freezing Bodies

[ad_2]