[ad_1]

From NASA to SpaceX, numerous space agencies and private spaceflight companies have bold plans to send humans to Mars, possibly even within the next few decades.

Given NASA’s ambitious plans to land astronauts on Mars by 2040, a hot topic of debate has been who will get to represent humanity on the Red Planet. At the center of that discourse is the 70-year-old argument that an all-female crew would make the most sense both biologically and psychologically, and not just as a matter of diversity and representation.

This argument is backed up by numerous scientific studies that cite the fact that an all-female crew would consume fewer resources than an all-male crew would, making the long-distance journey to Mars more efficient. However, many experts say this argument is no longer relevant and that a diverse crew would ultimately perform better.

Related: Diversity will be key to Artemis moon-to-Mars push, NASA officials say

Benefits of an all-female crew

Numerous studies since the 1950s have found that women occupy less space and consume lower amounts of life-support resources — like oxygen, water and food — than men do.

New calculations support that idea. In a paper published in April in the journal Scientific Reports, a team of researchers found that, on a 1,080-day mission, a four-member, all-female crew would need 3,736 pounds (1,695 kilograms) less food than an all-male crew would, amounting to a savings of $158 million.

“On average, women tend to be smaller than men, and so this metabolic advantage may be greater in women, as suggested by our calculations,” Jonathan Scott, a researcher at the French Institute for Space Medicine and Physiology and the study’s lead author, told Space.com. “This is why we concluded that there may be specific metabolic or life support resource operational advantages to all-female crews during future human space exploration missions.”

In the space industry, a lot of time and effort are spent trying to make resources smaller, lighter and more efficient, because the heavier a spacecraft is (including the weight of the fuel), the more fuel is required to lift it against Earth’s gravity. Therefore, an all-female crew would be a logical solution for long-term missions such as those to Mars, scientists have long argued.

In the latest study, Scott’s team used available data about astronauts’ physical fitness and average body mass and assumed that they would exercise twice a day, six days a week, which is the exercise regimen of astronauts on the International Space Station. (On the ISS, astronauts currently exercise for two hours each day, which is split into 30-45 minutes of aerobic exercises and 45 minutes of resistance or strength training.)

On a three-year mission, a crew of four women with heights between 4 feet, 11 inches and 6 feet, 3 inches (1.5 to 1.9 meters) — roughly the criteria for astronauts today — consumed 5% to 29% less resources than men across the same height range.

Because that was a large range of heights, the team also compared how resources would be consumed by astronauts in the 50th percentile of heights by sex, and found that a theoretical all-female crew would consume 11% to 41% less life-support resources than an all-male crew would. Given the limited data available on real astronauts, especially women, the team made a number of assumptions about future missions to complete the calculations, said Scott, who also conducts research on health care for astronauts for the European Space Agency’s Space Medicine Team.

However, Scott cautioned that the team “had to make a number of assumptions about future missions and how people would respond to them in order to complete the calculations.” Moreover, the team only had access to limited data from real astronauts, especially on female astronauts, so the findings are not comprehensive enough yet to inform real missions.

“At this point in time, I don’t think our study will have any influence [on the gender of the crew for a Mars mission], and I don’t think it should,” he said. “The two studies we performed, one on theoretical male and one on theoretical female astronauts, are just that — theoretical.”

“We need to go forward”

Despite similar findings from numerous studies, some scientists say that leaps in technology have made these kinds of calculations a lot less relevant than they were at the beginning of the space program.

“We do not need to go back in time; we need to go forward,” Dr. Saralyn Mark, health innovation director at Star Harbor, a spaceflight training facility in Colorado, told Space.com. “It is not a question of who is better, smarter, faster [or] takes less resources. It is a question of how well you train individuals and what is your value to a mission.”

Back in the late 1950s, each Mercury 7 astronaut — NASA’s first space travelers — had to be small enough to fit in the Mercury spacecraft’s small, one-man capsule. All of them were men, because women were banned from becoming military test pilots, which was the only entry point for astronauts at the time. In 1983, Sally Ride became the first American woman in space.

Related: The 1st human on Mars may be a woman, NASA chief says

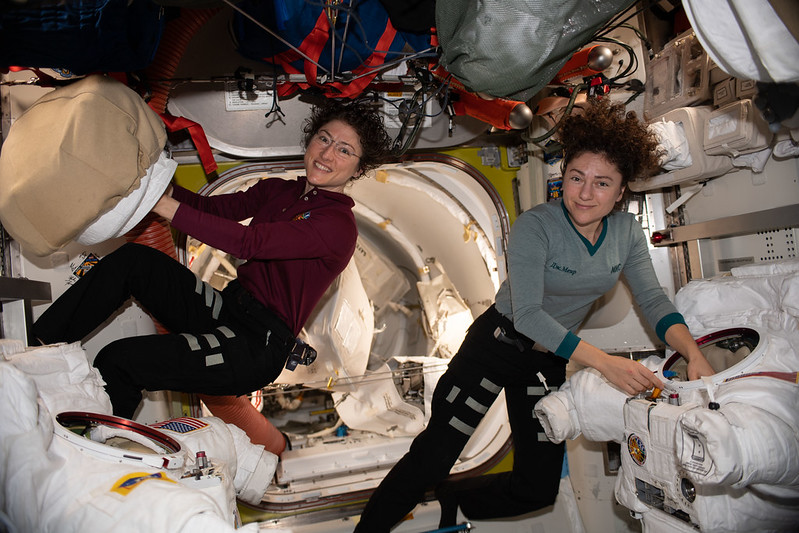

A lot has changed since then. So far, 78 women have flown to space, and NASA’s first astronaut class with equal numbers of men and women (four each) was in 2013. Spacecraft designs have evolved, too. The Orion spacecraft, NASA’s chosen vehicle for crewed missions to the moon and maybe even to Mars, is much less constrained than its predecessors and can carry four astronauts.

Diversity is key

Despite the statistics suggesting the theoretical benefits of an all-female crew, experts cautioned that numbers may not tell the whole story. Instead, they encouraged taking a broader view, and diversity is key to that perspective.

“If we are talking about trying to reduce the weight and volume of the things we send with humans, then we can also reduce the weight and volume of the humans involved — but that doesn’t mean it has to be all-female,” Michaela Musilova, former director of the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) habitat, told Space.com.

Experts echo a message they say is key to a mission’s success: A diverse crew is more efficient and more effective than a single-gender crew. So the idea of an all-female crew, however pragmatic it may sound, “would be a form of gender discrimination towards men,” Mark said.

“We don’t want to set up this binary competition,” she added. “In today’s world, we have the technology; we have the capabilities to democratize space to ensure that there is space for all.”

Instead, the focus should be on the numerous other skills of each individual and how the group operates as a whole.

“This idea of all-men or all-women — it’s just not realistic,” Gloria Leon, a professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Minnesota who studied mixed- and single-gender crews on multiple analog missions, told Space.com. “There’s so many other factors that go into the physiology of the individual and how that relates to their performance in a three-year mission.”

To study those factors, researchers rely on analog space missions that simulate trips to the moon and Mars missions on remote areas on Earth, like the HI-SEAS habitat in Hawaii. For a few months, these mock-mission participants live like they are on Mars, including completing research assignments and dealing with the 20-minute communication delay between Mars and Earth.

For a handful of those missions, Musilova specifically selected all-male or all-female crews to understand the differences; for most of the other missions, crews were not asked their gender or ethnicity details. She found that there was nothing gender-specific that influenced the efficiency or success of various teams but that the greater the crew’s diversity was, the more the members were able to learn from one another, ultimately helping them solve challenges and gain new perspectives, she said.

“These days, gender really shouldn’t play such a big role,” Musilova said. “We should really focus more on having competent and capable people who, for space missions, are empathetic, can communicate well, are adaptable, patient and trained well for all the difficult situations that the crews may go through and that they train together as a crew so they can work really well together and face all those challenges and problems together.”

So what would diversity on a Mars mission look like? The crew for NASA’s Artemis 2 mission, which will fly a woman beyond low Earth orbit for the first time, is a good start, but there’s still a long way to go. For example, there is no research available on the effects of spaceflight on intersex or transgender people. Beyond genders, there is a yawning gap in the nationalities of astronauts who have flown to space, and a crewed mission to the Red Planet could be an opportunity to change that.

“I want everyone to see a part of themselves in the faces of those who go to Mars, because it is basically a continuation of our species on another planet,” Mark said.

[ad_2]