[ad_1]

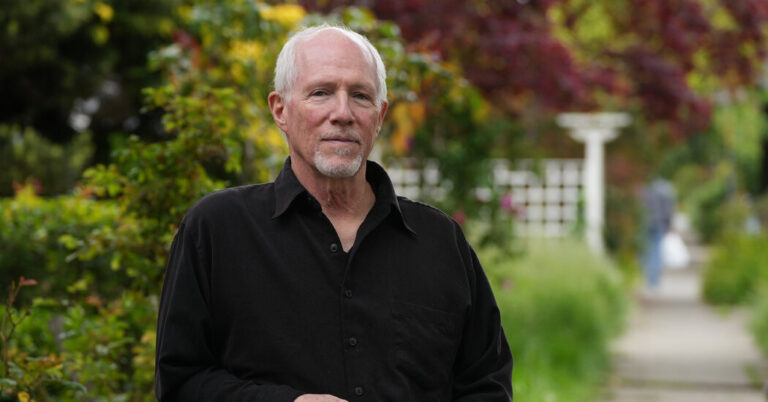

Last summer, Joe Loree made an appointment to see his urologist. He’d occasionally noticed blood in his urine and wanted to have that checked out. His doctor ordered a prostate-specific antigen, or P.S.A., test to measure a protein in his blood that might indicate prostate cancer — or a number of more benign conditions.

“It came back somewhat elevated,” said Mr. Loree, 68, an instructional designer who lives in Berkeley, Calif. A biopsy found a few cancer cells, “a minuscule amount,” he recalled.

Mr. Loree was at very low risk, but nobody likes hearing the c-word. “It’s unsettling to think there’s cancer growing within me,” he said.

But because his brother and a friend had both been diagnosed with prostate cancer and had undergone aggressive treatment that he preferred to avoid, Mr. Loree felt comfortable with a more conservative approach called active surveillance.

It typically means periodic P.S.A. assessments and biopsies, often with M.R.I.s and other tests, to watch for signs that the cancer may be progressing. His hasn’t, so now he can get P.S.A. tests every six months instead of every three.

Research shows that a growing proportion of men with low-risk prostate cancer are opting for active surveillance, as medical guidelines now recommend.

The diagnosis used to lead directly to aggressive treatment. As recently as 2010, about 90 percent of men with low-risk prostate cancer underwent immediate surgery to remove the prostate gland (a prostatectomy) or received radiation treatment, sometimes with hormone therapy.

But between 2014 and 2021, the proportion of men at low risk of the cancer who chose active surveillance rose to nearly 60 percent from about 27 percent, according to a study using data from the American Urological Association’s national registry.

“Definitely progress but it’s still not where we need to be,” said Dr. Matthew Cooperberg, a urologic oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and lead author of the study.

Changing medical practice often takes a frustratingly long time. In the study, 40 percent of men with low-risk prostate cancer still had invasive treatment. And approaches vary enormously between urology practices.

The proportion of men under active surveillance “ranges from 0 percent to 100 percent, depending on which urologist you happen to see,” Dr. Cooperberg said. “Which is ridiculous.”

The latest results of a large British study, recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine, provide additional support for surveillance. Researchers followed more than 1,600 men with localized prostate cancer who, from 1999 to 2009, received what they called active monitoring, a prostatectomy or radiation with hormone therapy.

Over an exceptionally long follow-up averaging 15 years, fewer than 3 percent of the men, whose average age at diagnosis was 62, had died of prostate cancer. The differences between the three treatment groups were not statistically significant.

Although the cancer in the surveillance group was more likely to metastasize, it didn’t lead to higher mortality. “The benefit of treatment in this population is just not apparent,” said Dr. Oliver Sartor, an oncologist at the Mayo Clinic who specializes in prostate cancer and who wrote an editorial accompanying the study.

“It doesn’t help people live longer,” Dr. Sartor said of the treatment, probably because of what is known as competing mortality, the likelihood of dying from something else first.

Men whose P.S.A. readings and other test results indicate higher-risk tumors, or who have family histories of prostate cancer deaths, fall into a different category, experts cautioned.

“The point of screening is to find the aggressive tumors — a small minority, but they kill more men than any other cancer except lung cancer,” Dr. Cooperberg said.

But most prostate cancer grows so slowly, if it grows at all, that other illnesses are likely to prove lethal first, especially among older men. During the British study, one in five men died from other causes, predominantly cardiovascular or respiratory diseases and other cancers.

That’s why guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the American College of Physicians recommend against routine prostate cancer screening for men over 69 or 70, or for men who have less than a 10- to 15-year life expectancy. (Men ages 55 to 69 are advised to discuss the harms and benefits with health care providers before deciding to be screened.)

Newly revised guidelines from the American Urological Association recommend shared decision-making after age 69, taking into account age, life expectancy, other risk factors and patients’ preferences.

“If you live long enough, prostate cancer is almost a normal feature of aging,” Dr. Cooperberg explained. “By the 70s or 80s, half of all men have some cancer cells in their prostates.”

Most of those tumors are deemed “indolent,” meaning that they don’t spread or cause bothersome symptoms.

Nevertheless, about half of men over 70 continue P.S.A. screening, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open. Though testing declined with age, “they really shouldn’t be getting screened at this rate,” said the lead author Sandhya Kalavacherla, a medical student at the University of California, San Diego.

Even among men over 80, almost 40 percent were still getting routine P.S.A. tests. An elevated P.S.A. reading can prompt a cascade of subsequent tests and treatments, because “‘cancer’ is an emotionally charged term,” Dr. Sartor acknowledged. He still sees patients, he said, whose response to very low-risk cancer is, “I want it out, now.”

But treatment involves significant side effects, which often ease after the first year or two but may persist or even intensify. The British data showed, for instance, that six months after treatment, urinary leakage requiring pads affected roughly half of the men who’d had a prostatectomy, compared to 5 percent of those who underwent radiation and 4 percent of those under active surveillance.

After six years, 17 percent of the prostatectomy group still needed pads; among those under active surveillance, it was 8 percent, and 4 percent in the radiation group.

Similarly, men under active surveillance were more likely to retain the ability to have erections, though all three groups reported decreased sexual function with age. After 12 years, men in the radiation group were twice as likely, at 12 percent, to report fecal leakage as men in the other groups.

The financial costs of unnecessary testing and treatment also run high, as an analysis of claims from a large Medicare Advantage program demonstrate. The study, recently published in JAMA Network Open, looked at payments for regular P.S.A. screening and related services for men over 70 with no pre-existing prostate problems.

“The initial screening, which is unnecessary, triggers these follow-up services, a series of events catalyzed by anxiety,” said David Kim, a health economist at the University of Chicago and lead author of the study. “The further it progresses, the harder it is to stop.”

From 2016 to 2018, each dollar spent on a P.S.A. test on men over 70 generated another $6 spent for additional P.S.A. tests, imaging, radiation and surgery.

Extrapolated to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, Medicare could have spent $46 million for P.S.A. tests for men over 70 and $275 million in follow-up care, Dr. Kim said.

“We need to change the incentives, how providers get paid,” he said.

He suggested that refusing to reimburse them for procedures that receive low recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force could mean fewer inappropriate P.S.A. tests and less aggressive treatment in their wake.

Some urologists and oncologists have called for a different kind of shift — in nomenclature. “Why are we even calling it ‘cancer’ in the first place?” asked Dr. Sartor, who has argued against using the word for small, low-risk tumors in the prostate.

A less frightening label — indolent lesions of epithelial origin, or I.D.L.E., was one suggestion — could leave patients less inclined to see test results as lethal portents and more willing to carefully track a common condition that might never lead to an operating room or a radiation center.

[ad_2]