[ad_1]

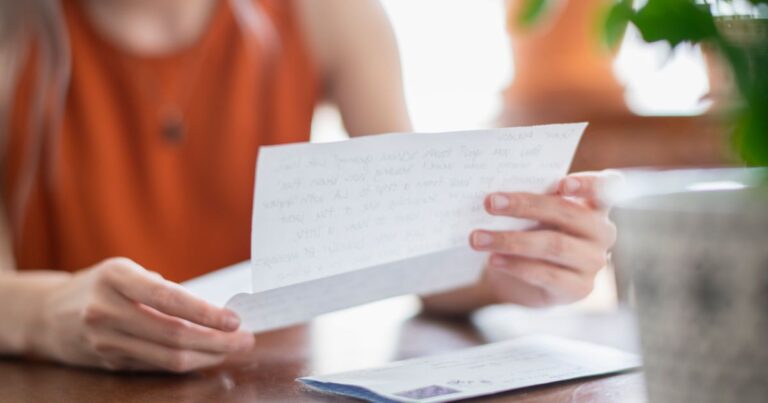

I read my mother’s suicide note for the first time at 36 years old while making chocolate chip protein pancakes for my daughter.

It was difficult to read — literally. It had been written on a hotel notepad 31 years ago and photographed as evidence after it was found. The photos sat in a filing cabinet until the case was closed, when the note was converted to microfiche. But I recently submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the police department for my mother’s death investigation case file. Then, the note was printed on white copy paper and handed over to me.

At the kitchen counter, I turned to flip the pancakes and then flip through the file, reading about the housekeeper who found my mother’s body, the interviews that police conducted with my family, the medical examiner’s report. My daughter played with Lego bricks at the kitchen table. I had planned to wait until she went to school to read the report, but the compulsion to learn about my mother’s death after all those years proved an overwhelming draw.

My mother died when I was 5 years old and my sister 2. I was told at the time that my mother had a “brain disease.” I suppose that was the way a professional had advised my dad to explain mental illness to a child as young as I was. I remember being in kindergarten with the school social worker and drawing a pink, blobby brain shape with a graphite gray spot on it.

My dad was not, is not, shy about his love for my mother. Every anniversary, he writes a column — poems, song lyrics, words — about how much he misses her and how proud of us she would be. When I was younger, these columns were published in the local newspaper. In recent years, they have transformed into moving Facebook posts with pictures of the grandchildren she will never get to meet.

As children, my dad took us to the cemetery often to “visit” my mom. My sister and I took turns choosing the flowers that we put in the upturned urn on her headstone and snuggling with a small, tan teddy bear he told us had belonged to her. My mother’s side of the closet stayed full of her clothes for decades, and mementos of her still remain in my dad’s home. We talked about the loss, but we never really talked about the woman, her life and her death beyond the superficial.

At some point in my childhood, I must have worked up the nerve to ask more questions about her, although I do not remember a specific conversation. That is when I learned that my mother had taken her own life at a hotel near our home. No additional details were forthcoming, and perhaps that is why, over the decades in between, I never asked any more questions. What more did I need to know, and what good would it do?

As a young child, I was often angry that I didn’t have my mother as a “room mom” or to celebrate Mother’s Day with. I was resentful when teachers assumed that it was a mother who packed my lunches and signed my permission slips. But as I grew, I got good grades and received scholarships to college, and I met and married an incredible partner. It did not seem to matter that I did not have a mother — until I became one myself.

My daughter was born healthy, beautiful and colicky. She cried nearly constantly for the better part of six months. Nothing I did seemed to help — breastfeeding, baby-wearing, multiple trips to the pediatrician. I spent the days and nights listening to her incessant, incriminating howls. The cries accumulated in my psyche as evidence that I didn’t deserve to be a mother, that I would never be good enough. I began to have fleeting thoughts of leaving like my mother had. I also wished she was there to help and reassure me.

I survived those early months, when I wasn’t fantasizing about starting a new life, by writing to my daughter. I wrote messages of love in the covers of books I ordered for each holiday and piled in her room. I wrote cards and letters, crying onto them while she cried in the background. I wrote over and over again to my daughter about how special she was, the joy she brought to our family, my hopes and dreams for her future.

I sealed the notes to my daughter in envelopes and stacked them into a pink safe I ordered for this purpose. If it turned out that I couldn’t stay, at least my daughter would have tangible evidence that her mother loved her.

Eventually, the crying subsided — and along with it, my thoughts of departure.

As my daughter has grown, I have been awed by her empathy, compassion and creativity while simultaneously feeling unworthy of the privilege of being her mother. I have tried to fix this through frenzy; I enrolled her in private school, fed her fruits and vegetables, minimized screen time. We moved to a bigger house, bought her a scooter with light-up wheels, adopted a guinea pig. Checking all of the boxes kept the feelings of inadequacy at bay for a while.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and we went through the same shock and upheaval as many families across the world. For my daughter, the stresses were perhaps compounded by my working as a nurse in the emergency department and my husband in law enforcement. Again, nothing I did or tried could fix how she felt.

Out of desperation, I resumed writing. I signed up for a writing workshop and penned a 78,717-word novel about a woman with a dead mother trying to parent her daughter through hard times. After months of revising the draft, trying to write the happy ending that I wanted for my characters — and for me and my daughter — I gave up. There were too many holes in the story, and the biggest was the protagonist’s relationship with her dead mother, i.e., my relationship with mine. I finally confronted the fact that to write the ending, I needed to look back to my beginnings, to my relationship with my mother. Perhaps there would be wisdom in unraveling our history.

I began my journey by obtaining my mother’s death investigation file and court records. In hindsight, it seems revealing that I would rather look through a police file than have an honest conversation with my family about who my mother was.

When I finally read my mother’s suicide note for the first time, five words jumped out at me.

“I was a horrible mother.”

I surprised myself by feeling not shocked or sad, but relieved by her words. “I am a horrible mother” had been the refrain in my mind for my daughter’s entire 9 years of life. Thirty-one years after my mother’s death, here was physical evidence of the thread that connected us across the decades.

It wasn’t until months later that I noticed additional text at the bottom, nearly impossible to make out. I had to reference the typed rendering in the police report. It was transcribed as my initials, then my sister’s, and then “I love you and I did the best things for you.”

Her last words were to tell us that she loved us and was trying to do right by us. I find this somewhat comforting. But having now known my daughter twice as long as my mother knew me, those words on that scrap of paper, and the intention, don’t make up for my loss.

Although my heart hurts for my mother and how sick she must have been, her actions sent out shock waves of trauma with intergenerational consequences. Their impact on me may be part of the reason that my daughter feels the hurts of the world so deeply.

But the moral of my mother’s story seems to be simple: My presence means more than perfection to my child. I hope that the more I am brave enough to ask the hard questions, and to speak and write honestly, the more my daughter and I can undo the “horrible mother” legacy, break the cycle and create a better future.

If you or someone you know needs help, dial 988 or call 1-800-273-8255 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. You can also get support via text by visiting suicidepreventionlifeline.org/chat. Additionally, you can find local mental health and crisis resources at dontcallthepolice.com. Outside of the U.S., please visit the International Association for Suicide Prevention.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

[ad_2]