[ad_1]

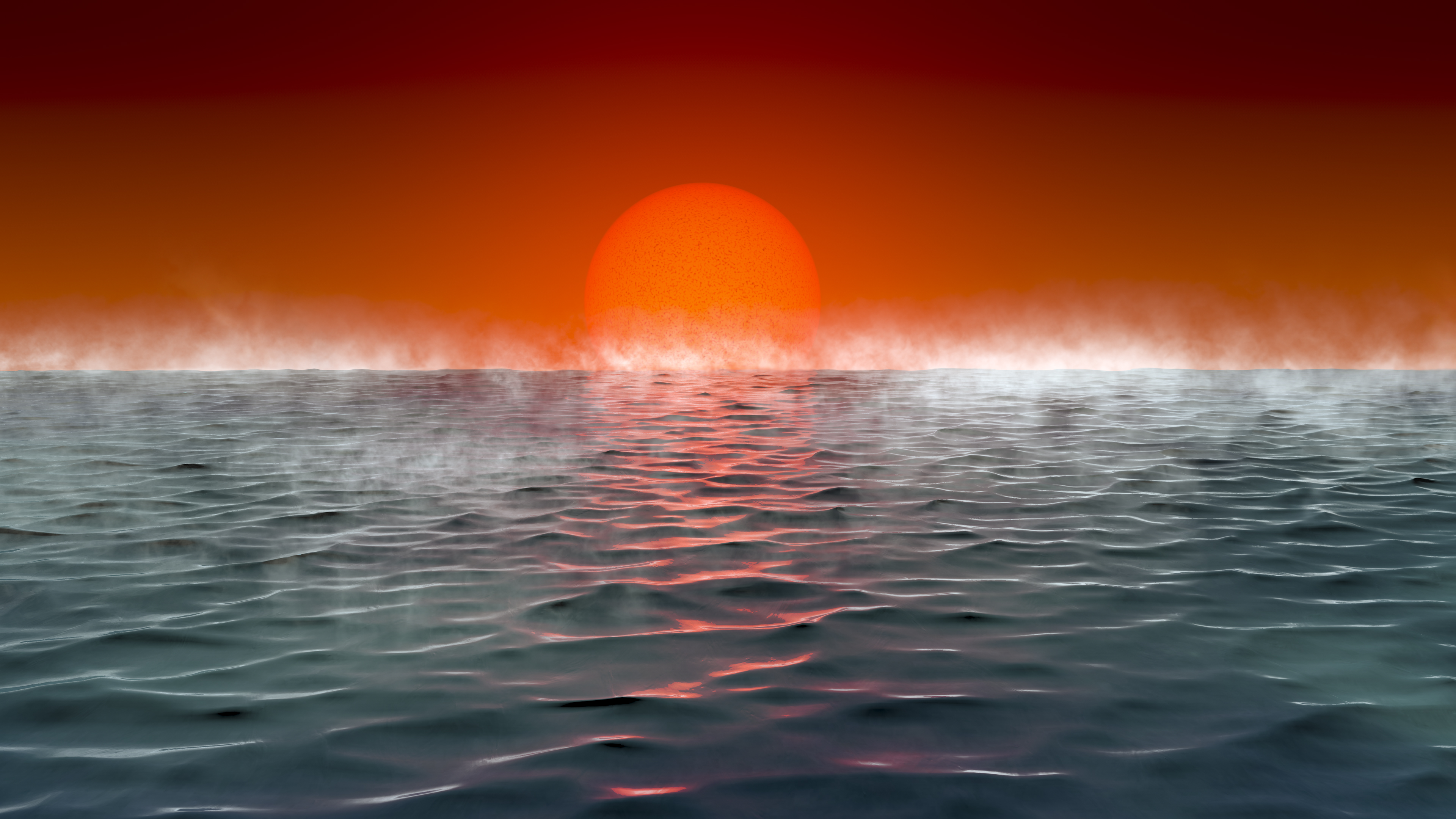

In 2021, astronomers proposed a new class of exoplanets that contain hydrogen-rich atmospheres and support vast liquid-water oceans, making these hypothetical worlds potential candidates in the search for alien life.

However, new research suggests that these “Hycean” planets would suffer from a catastrophic runaway greenhouse effect, thus limiting their potential for habitability.

Hycean worlds get their name from a combination of “hydrogen” and “ocean,” because these worlds — which would be larger than Earth but smaller than any of the giant planets in our solar system — are covered in thick, dense layers of a hydrogen atmosphere and could support vast liquid-water oceans.

Related: The search for alien life

Although no Hycean worlds have been confirmed to exist, the massive exoplanet survey by NASA’s Kepler mission identified several candidate worlds that, based on estimates of their size and density, might be Hycean planets.

Astronomers are very interested in Hycean worlds. Where there’s liquid water, there’s a potential home for life as we know it. And because of their thick atmospheres, these planets can potentially exist in a much broader range of orbits around their parent stars without sacrificing their habitability, so there’s even the chance that life is more common on Hycean worlds than our own.

But current research on the habitability of Hycean worlds isn’t very detailed, and it relies on relatively simplistic models of atmospheric dynamics to understand how these planets can work. To remedy this, a team of researchers developed a more sophisticated approach for studying how a more accurate treatment of Hycean atmospheres and oceans would change our understanding of their behavior around different kinds of stars.

‘Supercritical’ oceans

The researchers found that the presence of a thick, hydrogen-dominated atmosphere radically changes how these planets behave, compared with a world like Earth. Our planet has a thick atmosphere too, but that atmosphere is composed of heavier elements, like nitrogen and oxygen. The ability of those elements to block or allow in specific wavelengths of light affects how warm the surface is for a given amount of solar radiation coming in.

But hydrogen acts differently: It blocks and admits different wavelengths of light, which, in turn, changes how the surface responds to sunlight. For example, the researchers found that if a planet with an atmospheric pressure 10 to 20 times Earth’s (which is typical for Hycean worlds) were to be placed in the same orbit as Earth, its oceans would become “supercritical.” That means the planet’s temperatures would rise beyond the boiling point, which would lead to the oceans’ evaporation and complete disappearance.

The researchers also found that the mixture of water vapor and hydrogen in Hycean planets’ atmospheres changes their habitability. Hycean worlds cannot receive nearly as much sunlight as we previously thought before their oceans become too hot to sustain themselves as a liquid.

Previous models had placed the inner edge of the habitable zone, the region where surface temperatures on a world are just right to sustain liquid water, right around one astronomical unit (AU), the distance at which Earth orbits the sun. But the new calculations push the inner edge to 1.6 AU for worlds with similar air pressures as Earth. For Hycean worlds with 10 times the air pressure, the inner edge of the habitable zone is now thought to be 3.85 AU.

This means that Hycean worlds cannot live close to their parent stars, thereby limiting their range of habitability. Indeed, the researchers concluded that all the known potential Hycean worlds exist inside these new habitable limits and, therefore, are unlikely to host liquid-water oceans — and any chance for life. The researchers have submitted their work for publication in The Astrophysical Journal, and a preprint is available via arXiv (opens in new tab).

But there’s still hope for these exoplanets’ habitability. Hycean worlds can exist and sustain liquid-water oceans far beyond the outer edge of the habitable zones for Earth-like planets, so we may still find new promising candidates. The researchers hope to continue their work with even more detailed simulations to capture the complex and fascinating dynamics of these mysterious hypothetical worlds.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or Facebook (opens in new tab).

[ad_2]