[ad_1]

-

Ceirra Zeager thought her pounding heart was excitement from attending her first school dance.

-

But it turned out to be the beginning of a heart attack, caused by a congenital heart defect.

-

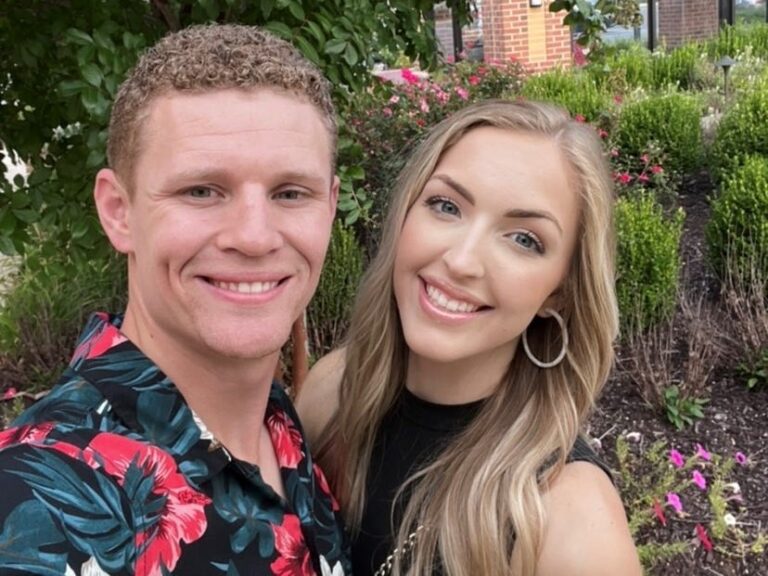

Zeager, now 23, is sharing her story as a volunteer for the American Heart Association.

As a high school freshman in rural Pennsylvania, Ceirra Zeager was a wallflower who focused on her schoolwork and art. She didn’t play sports or music, and had just two close friends — one of whom was her sister.

So when Zeager, then 14, went to the winter formal and danced with a boy for the first time, she wasn’t sure how to interpret her racing heart, which continued to pound long after she’d returned home. “I was thinking, ‘Is this how it is to have feelings?'” Zeager, now 23, told Insider.

But the next morning, Zeager’s “butterflies” had morphed into such a deep fatigue and heaviness in her arm that she struggled to put on her shirt. When she tried to walk to her parents’ bedroom for help, her vision narrowed, her ear flooded with warmth, and she collapsed.

“Before I knew it, I was on the floor,” Zeager said. “It felt like an elephant was on my chest.”

Zeager later learned she’d suffered a heart attack, and is now sharing her story as a volunteer for the American Heart Association’s Go Red For Women “Real Women” campaign. She wants other other young women to know the signs of a heart attack, and to speak up when they know something is wrong.

A doctor at the hospital told Zeager it was just ‘teenage anxiety’

The morning after the dance in 2014, Zeager’s dad, a pharmacist, saw her on the ground and asked if the family needed to go to the hospital instead of her brother’s birthday party, as planned. “I have no idea what’s going on, but I think we do,” she said.

At the hospital, Zeager said she wasn’t treated like someone in an emergency situation. She waited hours to be seen and developed “an intense burning pain” in her upper arm, but wasn’t given pain medicine. She now knows arm pain is often a sign of heart attacks in women.

Eventually, a doctor told Zeager she likely had “teenage anxiety.”

“It really broke me to hear that because I felt embarrassed that my whole family was there, and I was ruining my brother’s birthday get-together,” Zeager said.

Still, the doctor recommended Zeager visit a children’s hospital just to be safe. While there, she learned tests had identified a blockage in or around her heart, and that she needed to undergo a cardiac catheterization procedure to identity the location of the clot.

When Zeager awoke from the surgery, more than 12 hours after showing up at the first hospital, she saw her sister crying. “You had a heart attack,” her sister said.

Zeager learned she had ‘sticky’ blood and a hole in her heart

Later testing revealed Zeager had elevated lipoprotein A, which means her red blood cells are “extra sticky,” leading to a blood clot. She was also born with a hole in her heart, called patent foramen ovale (PFO), which allowed the clot to get lodged in her coronary artery, causing the heart attack.

While about 1 in 4 people have PFO, it alone usually doesn’t cause any problems, according to the Mayo Clinic. But for Zeager, the defect in combination with high lipoprotein A levels — something that can’t be controlled through diet and exercise — was dangerous.

Zeager’s treatment included surgery to repair the hole, six months on blood thinners, and a several-week long hospital stay.

About seven years later, Zeager experienced extreme fatigue, but chalked it up to the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic or planning her wedding. But a cardiologist told her she needed open-heart surgery to repair a leaky heart valve that had been damaged during the heart attack.

Zeager underwent the surgery in February 2021, just a few months after her wedding. The emotional recovery was the hardest part, she said.

“You’re swollen, you’re bruised, you don’t feel like yourself, you’re on all sorts of painkillers, and you’re just barely making it through each day,” she said. While she’s usually a positive person, she said, “In that moment, I was not positive. I was not happy.”

Since then, Zeager, now a human resources professional in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, maintains a healthy lifestyle, but still has an “ejection fraction” — a measure of heart strength — around 44%. A healthy range is 50% to 70%, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

That may mean she’ll be unable to safely carry a pregnancy. “Having that taken away from you as a woman is very, very hard,” she said.

But Zeager finds comfort in spreading her message. “Listen to your body, advocate for yourself, and try to find the silver lining,” she said. “It’s cliche, but it’s so true.”

Read the original article on Insider

[ad_2]