Technology that could help humanity land heavy hardware on Mars will get an in-space test early next week.

A United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V rocket is scheduled to launch the Joint Polar Surveyor System-2 (JPSS-2) weather satellite from California’s Vandenberg Space Force Base early Tuesday morning (Nov. 1).

JPSS-2 — a U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration craft that will help researchers improve weather forecasts and monitor the impacts of climate change, among other tasks — isn’t the only payload onboard the Atlas V. Also going up on Tuesday is the Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator (LOFTID) craft, a technology demonstrator whose applications could extend beyond our home planet.

Related: Powerful new Earth-monitoring satellite JPSS-2 to study weather’s ‘butterfly effect’

A new type of landing gear

LOFTID is an expandable aeroshell, a type of heat shield that engineers are eyeing for missions to the Red Planet. The thin Martian atmosphere makes landing there tricky; incoming spacecraft encounter some drag, but not nearly as much as they feel in Earth’s air.

So it takes more than parachutes to get payloads down safely on Mars. NASA’s golf-cart-sized Spirit and Opportunity rovers, for example, also employed bouncy air bags that cushioned their fall. And the agency developed a rocket-powered sky crane to land its Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, both of which are about the size of an SUV and weigh roughly 1 ton (here on Earth, anyway; they’re lighter on Mars, where the surface gravity is just 40% as strong as our planet’s).

Those missions pretty much maxed out the weight limits of the sky crane, however. New entry, descent and landing tech will be needed to get super-heavy payloads — habitat modules for a future research base, for instance — safely down on Mars, NASA officials have stressed.

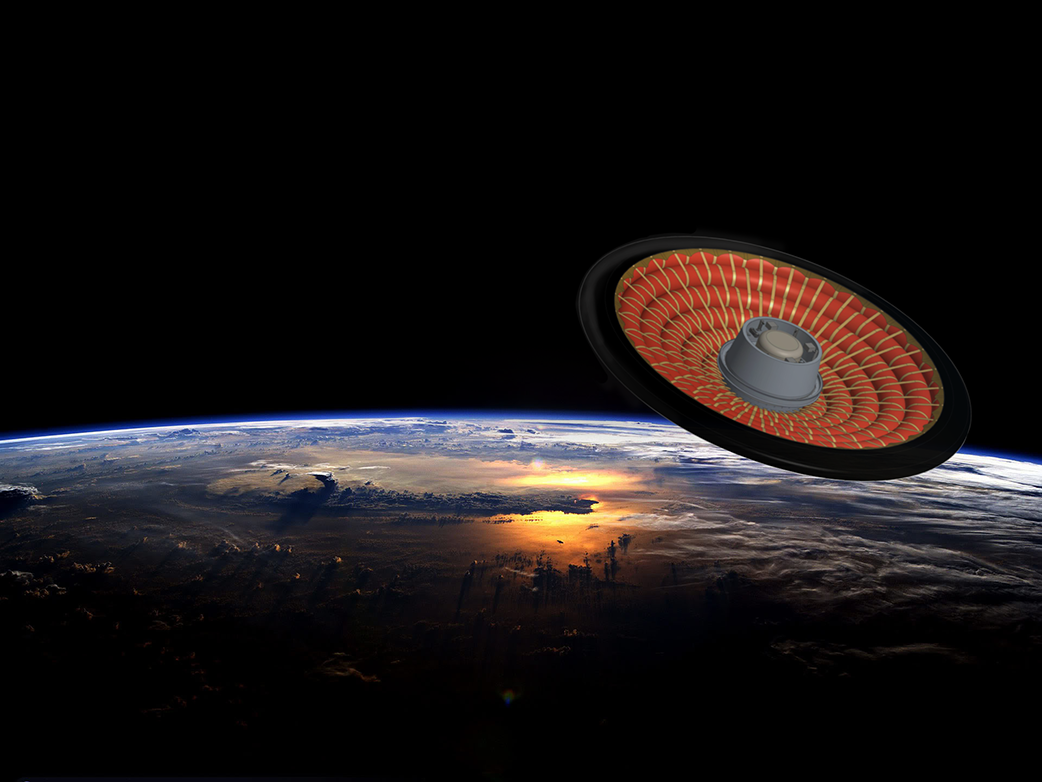

Expandable aeroshells are one possible solution. These saucer-like structures are designed to compress tightly enough to launch aboard conventional rockets. But they inflate considerably upon arrival at their planetary destination, potentially providing enough atmospheric drag to help land objects much more massive than Perseverance or Curiosity. (Decelerators aren’t the entire answer; parachutes would still be part of the plan as well.)

The $93 million LOFTID project began just five years ago, but the basic idea goes way back.

“The original concept actually comes from the ’50s and ’60s,” Joe Del Corso, LOFTID project manager at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, said during a press conference earlier this month. “Unfortunately, during that time, they did not have the materials or structures; they were not sufficiently advanced enough to actually realize the capability.”

NASA has conducted ground and atmospheric tests with expandable aeroshells, including a 2015 trial that carried one high into the skies above Hawaii aboard a giant balloon. (That test didn’t go according to plan, however; the supersonic parachute attached to the aeroshell ripped apart during the descent.)

But LOFTID will take the testing to a new level.

“It’s the first low Earth orbit flight test of this technology, and the largest-scale test article to date,” Trudy Kortes, director of technology demonstrations at NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, said during the press conference.

Related: To land safely on Mars, keep straight and fly right

The flight plan

LOFTID is packed tightly inside a bag 7.4 feet tall and 4.3 feet wide (2.3 by 1.3 meters). It sits below JPSS-2 on the Atlas V’s Centaur upper stage.

The Centaur will deploy JPSS-2 into a sun-synchronous polar orbit about 28 minutes after liftoff on Tuesday, then maneuver its way onto a re-entry path. Seventy-five minutes into the flight, the Centaur will release LOFTID, which will head back down to Earth.

The aeroshell will have expanded to its full width of 19.7 feet (6 m) by this point. LOFTID will barrel through our atmosphere, experiencing maximum temperatures around 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius) before deploying parachutes and splashing down softly in the Pacific Ocean near the Hawaiian islands.

Mission team members will pore over the data LOFTID gathers on the way down, using it to round out their understanding of expandable aeroshells’ capabilities and potential. That potential is intriguing, and it’s not limited to Red Planet missions, Kortes said.

“This technology can ultimately enable new missions for us to Mars [and] Venus; even the largest moon of Saturn, Titan, becomes a possibility because of the dense atmosphere there,” she said. “And it can be used for payload returns to Earth as well.”

ULA is particularly interested in that return-to-Earth angle. The launch company is partnering with NASA on LOFTID, under an unfunded Space Act Agreement, because it wants to assess the possible use of decelerators on missions of its future Vulcan Centaur rocket, the successor to the Atlas V.

ULA wants to reuse the Blue Origin BE-4 engines that power Vulcan Centaur’s first stage, and expandable aeroshells like LOFTID could be a good way to get this valuable hardware safely back to Earth.

“All of the data we get out of the LOFTID mission will be used to help correlate models and gain a much better understanding of what the Vulcan reuse system will face,” James Cusin, an operations engineer in ULA’s Advanced Programs division, said in a statement (opens in new tab).

Mike Wall is the author of “Out There (opens in new tab)” (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall (opens in new tab). Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom (opens in new tab) or on Facebook (opens in new tab).