Christmas came one day early for a lone geologist stationed on the Red Planet.

NASA’s InSight mission touched down on Mars in November 2018 to peer inside the planet, mapping its layers and faultlines. And on Dec. 24, 2021, the lander made a remarkable detection, catching seismic waves from a sizeable meteoroid impact. Photos taken from orbit made the signal even more intriguing, because scientists tied the seismic detection to the sight of a large, fresh crater.

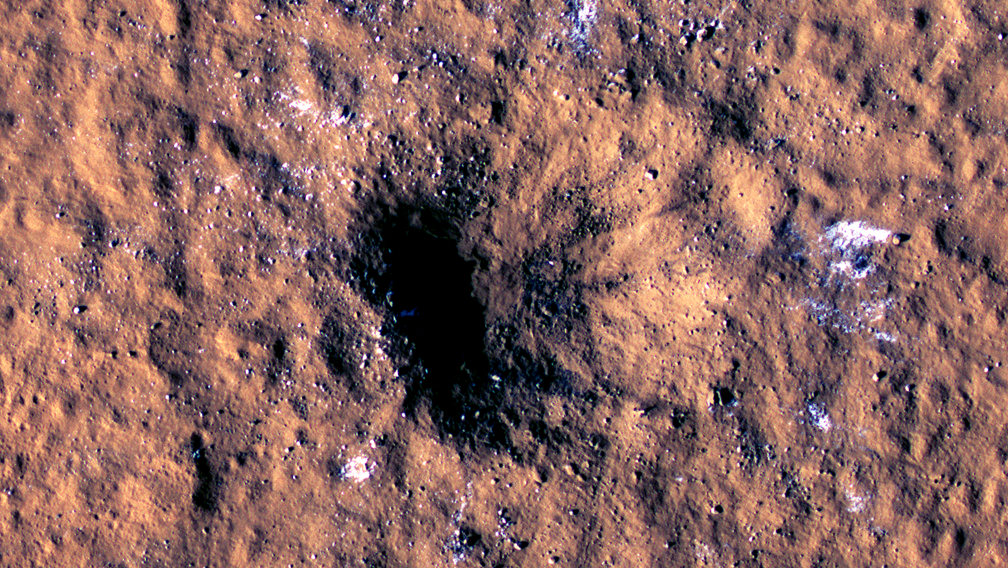

“It was immediately clear that this is the biggest new crater we’ve ever seen,” Ingrid Daubar, InSight impact science lead and a planetary scientist at Brown University, said during a news conference held on Thursday (Oct. 27).

“We thought a crater this size might form somewhere on the planet once every few decades, maybe once a generation,” Daubar said. “So it was very exciting to be able to witness this event, and to be lucky enough that it happened while InSight was recording seismic data — that was a real scientific gift.”

Related: NASA’s Mars InSight lander snaps dusty ‘final selfie’ as power dwindles

In September, InSight scientists announced four detections of meteorite impacts, each also tied to a fresh crater, that were made in 2020 and earlier in 2021.

But these were small impacts: None produced seismic signals stronger than a magnitude 2 quake. InSight team members had deemed it unlikely that they’d see signals from more powerful strikes, so the lander’s Christmas Eve data were a bolt from the blue. Those observations pointed to an impact that clocked in at magnitude 4 and produced a crater more than 430 feet (130 meters) wide. (InSight also observed a similar impact in September 2021, which the mission team described in the scientific papers announcing these findings.)

But even while InSight scientists were digging into what the Christmas Eve impact might mean, scientists with NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which has been studying the Red Planet since 2006, made a different discovery when they spotted a fresh, large impact crater.

“When we first saw this image, we were extremely excited,” Liliya Posiolova, orbital science operations lead for MRO at Malin Space Science Systems in California, said during Thursday’s briefing. “This was nothing like we’ve seen before.”

Posiolova and her colleagues first spotted the fresh crater in data gathered by MRO’s Context Camera. The crater and the rays of debris circling the impact site filled an entire frame, 19 miles (30 kilometers) wide. “We needed to take two more images on the sides to capture the entire perturbance area.”

Daubar said that the crater itself stretches about 500 feet (150 m), which she compared to two city blocks and noted was 10 times the size of a typical new crater on Mars. Posiolova said that fresh impact craters usually look like mere smudges in MRO’s data.

Working backward from the size of the crater, scientists estimated that the asteroid that slammed into the Red Planet was between 16 feet (5 m) and 40 feet (12 m) wide before it met its fate. Had it struck Earth, a rock of that size would likely have burned up in Earth’s atmosphere, but Mars’ thin atmosphere doesn’t do much to protect the surface.

Thanks to the meteor’s size, the impact dug deep enough into the Martian surface to throw up boulder-size chunks of rock and water ice. “Most exciting of all, we saw clearly in the high-resolution images that a whole lot of water ice had been exposed by this impact,” Daubar said. “This was surprising because this is the warmest spot on Mars, the closest to the equator, we’ve ever seen water ice.”

She noted that because the impact would likely have destroyed most of the meteoroid itself, the ice probably doesn’t mean that the impactor was a comet. Instead, the team is confident that the ice was sheltering below the surface of Mars. Now that the ice is exposed on the surface, scientists see orbital images that suggest it’s disappearing, vaporizing away into the atmosphere.

Glimpses into the crust

The unexpected ice find isn’t the only information the impact is giving scientists, thanks to InSight’s seismic data.

That data include the first observations of surface waves that the InSight mission has shared. When a marsquake occurs, the loudest signals come from what geologists call P-waves and S-waves. Both of those types of seismic wave convey information about the interior of the planet because of how they respond to different layers of rock.

But surface waves give scientists a way to study the Red Planet’s crust at a large scale. “The nice thing about surface waves is they tell you about the crust not just where the lander is sitting, but they look at the crust as they’re moving across a planet,” Bruce Banerdt, InSight principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said during the news conference. “So the whole path between the event — in this case, the impact — and InSight is sampled by the surface waves as they move across the planet.”

The crater from the Christmas Eve impact is located about 2,200 miles (3,500 km) away from the lander, so its surface waves let scientists peer into a long swath of crust. (The September impact was more distant, at nearly 4,700 miles or 7,500 km away from InSight.)

“From the very beginning of our planning, we thought we were going to use surface waves to locate quakes, use the surface waves to probe the structure of the crust,” Banerdt said.”But for the first three years of the mission, we saw no surface waves.” Now, InSight has finally caught these waves, thanks to the two large impacts.

While the large impacts are particularly striking events, InSight scientists are also learning from much less dramatic signals. Separate research also published today based on data from InSight find that Mars may still hide some molten magma after all, despite many scientists’ belief that the planet is geologically dead.

That study identified InSight detections of more than 20 marsquakes in a region called Cerberus Fossae, where a network of fractures dominates the landscape. The researchers believe these quakes are the signature of molten rock just under the crust.

“It is possible that what we are seeing are the last remnants of this once active volcanic region, or that the magma is right now moving eastward to the next location of eruption,” Simon Staehler, lead author of the new research and a seismologist at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, said in a statement.

The impact findings are described in two papers published Thursday in the journal Science; the magma research is described in a paper published Thursday in the journal Nature Astronomy.

The new findings may be the last published from InSight before a more somber announcement from the mission. The lander is running low on power due to dust buildup on its solar panels and a storm-darkened sky, and the seismometer is currently observing for only eight hours every four Martian days.

InSight personnel have been anticipating the end of the mission for months now.

“That’s a sad thing to contemplate, but InSight has been working marvelously for the last four years,” Banerdt said. “Even now as we’re winding down, we’re still getting these amazing new results.” The lander caught its largest marsquake yet in May; Banerdt said that team members currently expect the mission to end in four to eight weeks.

“What an awesome capstone science result to end on,” Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said of the Christmas Eve impact during the news conference. “I mean, literally going out with a bang.”

Email Meghan Bartels at [email protected] or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.