[ad_1]

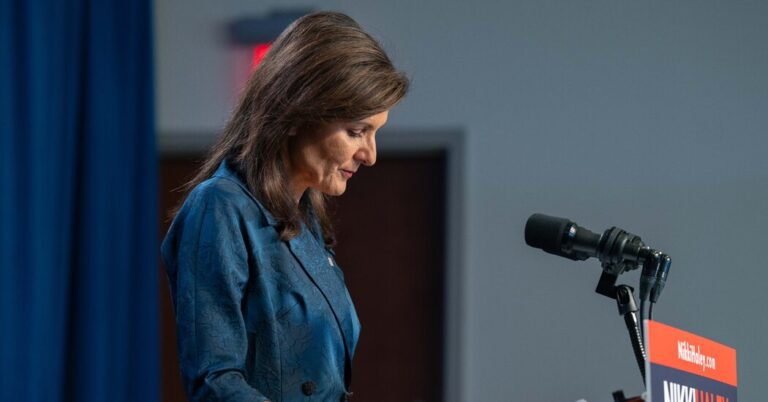

After absorbing bruising losses in the Super Tuesday primaries, Nikki Haley, the former governor of South Carolina, announced on Wednesday that she was ending her presidential campaign.

In handing the party’s nomination to former President Donald J. Trump, a rival with whom she clashed bitterly by the end, she declined to endorse him. Instead, she challenged him to win over her supporters: a cohort of more moderate Republicans who could not prevent his nomination, but could potentially hurt his prospects in the fall against President Biden.

“In all likelihood Donald Trump will be the Republican nominee when our party convention meets in July. I congratulate him and wish him well,” she said, adding that it was now “his time for choosing.”

Her decision brings to a close the latest struggle over the soul and direction of the Republican Party, a lopsided fight that has stretched back to Mr. Trump’s first presidential run in 2016. She had come to represent a small but not insignificant number of Republicans who saw her as their last, best chance to turn the page on the former president’s divisive and no-holds-barred politics.

For months and in increasingly urgent language, Ms. Haley, who was Mr. Trump’s first ambassador to the United Nations, had tried to paint her former boss as an aging, mentally unsound agent of chaos, unrepentant in his disparagement of veterans and service members and unwilling to remain faithful to the Constitution.

But she made it clear she was no member of the resistance. Nor was she able to loosen Mr. Trump’s grip sufficiently on a vast majority of the party.

If anything, her campaign revealed the extent to which she was out of touch with today’s G.O.P. — she was not a bomb-thrower or a natural culture warrior, like Mr. Trump or Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida, another former rival. Her unwavering support for Ukraine’s battle against Russia and for Western alliances like NATO that Mr. Trump has threatened to upend put her at odds with the party’s base on the United States’ place in the world. She failed to connect with the white rural voters who have propelled Mr. Trump, appealing instead to younger people, college-educated voters and independents.

She absorbed loss after loss, including in her home state last month. That streak culminated in Mr. Trump’s Super Tuesday blowout, which laid plain the near-impossibility of a path forward. Of the 15 states that voted, Ms. Haley won just Vermont, to add to her only other primary victory, on Sunday, in the District of Columbia.

While Ms. Haley highlighted fractures among Republican voters, her argument that only she could beat Mr. Biden in November was undercut by some polls giving Mr. Trump the lead over the president in a hypothetical general-election matchup. She faced intense pressure from Republican officials who feared a post-Super Tuesday campaign would further divide the party and bolster Mr. Biden’s re-election bid.

After she dropped out, Mr. Biden quickly sought to capitalize. “Donald Trump made it clear he doesn’t want Nikki Haley’s supporters,” he said in a statement. “I want to be clear: There is a place for them in my campaign.”

In his own statement posted to social media before her speech, Mr. Trump appeared to signal that he had no intention of being gracious, saying Ms. Haley was “trounced” and had been funded and propped up by “Radical Left Democrats.”

“I’d like to thank my family, friends, and the Great Republican Party for helping me produce, by far, the most successful Super Tuesday in HISTORY,” Mr. Trump said, “and would further like to invite all of the Haley supporters to join the greatest movement in the history of our Nation.”

Once a rising conservative star, Ms. Haley became the first woman and woman of color to lead South Carolina, aided by the same ultraconservative and anti-establishment Tea Party forces that Mr. Trump rode on his path to the White House.

When she jumped into the race in February 2023, she was Mr. Trump’s first major challenger. She withstood a field of more than a dozen candidates to become his last. Through the course of her campaign, she gradually moved from veiled swipes at her former boss to a full-throated rebuke of him and his grip on the machinery of the Republican Party.

She accused him of converting the G.O.P. into his “playpen,” of seeking to use the Republican National Committee as his “legal slush fund” for his pending criminal cases — he faces 91 felony counts in four different cases — and of costing Republicans victories up and down the ballot. Still, until the end, she continued to declare she was not “anti-Trump.”

Behind it all was a cautious and conventional campaign. She repeated her stump speech almost word for word, event to event, and rarely took questions from voters or the news media. She opted against stunts to grab headlines and dodged questions about whether she would ultimately endorse Mr. Trump.

She pursued what she saw as a disciplined effort to stitch together a coalition: those who liked Mr. Trump’s policies but had wearied of his baggage, others drawn to her call to return the party to fiscal responsibility and international leadership and a smaller contingent of anti-Trump Republicans and independent voters eager to leave the Trump era behind.

Her attempts to speak to all factions of a fractured G.O.P. gave her staying power in the race but were also a liability. Some voters liked her message but wished she had made her case against the former president more strongly, and much sooner. Her calibrated approach to issues like abortion and foreign policy gave Mr. Trump and others room to attack her in turn as too conservative to win in November or not conservative enough for the party.

Ultimately, Mr. Trump’s voters were never swayed. In the final chapters of the race, the candidate who tried to be all things to all Republicans stood for too little and held appeal for too few.

Making the case for generational change

Ms. Haley, 52, had cast herself as a “new generational leader” who could take on establishment Democrats and Republicans in Washington, move her party past the “drama and chaos” of the former president and comfortably defeat Mr. Biden. At her campaign events, voters tended to cite her foreign policy credentials, executive experience and her approach to the issue of abortion as the top reasons for their support.

“We’re ready — ready to move past the stale ideas and faded names of the past,” Ms. Haley told supporters as she began her campaign last year in Charleston, S.C.

She was the only woman in the Republican race, and her candidacy excited young girls, who often presented her with friendship bracelets, as well as voters who believed it was long past time for the nation to have its first female president. Some of her most devoted volunteers were women who appreciated her quotations from Margaret Thatcher and jabs at the “fellas,” her rivals for the nomination.

“I like to describe her as iron disguised as silk,” Kim Rice, her state co-chairwoman in New Hampshire, said in a December interview.

On the campaign trail, Ms. Haley, a former accountant, sought to replicate the thrifty playbook that had allowed her to win tough races before: She ran a tight budget, keeping her operation lean and her overhead low. She flew commercial for a vast majority of the campaign and stayed at moderately priced hotels. She left most of her early television advertising spending to a super PAC supporting her bid. And she reviewed her aides’ cash-flow spreadsheets obsessively.

She also tried to thread the needle between the moderate and far-right factions of her party. Her endorsers included Chris Sununu, the popular Republican governor of New Hampshire, and Will Hurd, a former Texas congressman who had briefly run for president, too, staking out a clearer anti-Trump lane. They also included Don Bolduc, a retired Army brigadier general and 2020 election denier who unsuccessfully ran for Senate in New Hampshire.

Ms. Haley took many hard-line positions similar to Mr. Trump’s, particularly on immigration. Wielding her position as the daughter of Indian immigrants — legal immigrants, Ms. Haley always declared — she called for a mass deportation of undocumented immigrants and echoed some of Mr. Trump’s language about militarizing the southern border.

She faced blowback from Democrats, women’s rights groups and transgender rights activists for saying that transgender girls playing in school sports was the “women’s issue of our time,” and for appearing to suggest that allowing “biological boys” in girls’ locker rooms was connected with the high rate of teenage girls who have considered suicide. She eventually modified her statements so as not to link the two issues.

In the fall, breakout performances on the national debate stage gave her candidacy a jolt. She stood out in particular for her answers on questions about abortion, an issue Republicans have struggled with after the conservative majority on the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, doing away with constitutional protections for abortion rights just ahead of the 2022 midterm elections. Protecting access at the state level proved potent for Democrats in those races and every election since.

Ms. Haley, who often described herself as “unapologetically pro-life,” backed harsh restrictions on the procedure as governor of South Carolina, and said she would have signed a ban on abortions after six weeks of pregnancy. Toward the last days of the campaign, she walked back her apparent support for a contentious Alabama Supreme Court ruling that raised legal questions about access to reproductive medicine and fertility care.

But voters tended to most remember her impassioned defenses of women and her declaration that Republicans must stop “demonizing” the issue of abortion. “Stop the judgment,” she said at a November primary debate in Miami. “We don’t need to divide America over this issue anymore.”

Ms. Haley began to reel in the support of establishment Republicans and Wall Street donors looking for an anti-Trump alternative. Beyond her debate showings, she was helped by some polls at the time showing that she would fare better than Mr. Trump against Mr. Biden, and by the departures from the race of former Vice President Mike Pence and Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina, a home-state rival who would go on to endorse Mr. Trump.

She received an 11th-hour boost in November when she obtained the endorsement of Americans for Prosperity Action, a deep-pocketed organization founded by the billionaire industrialist brothers Charles and David Koch.

Still, her own mistakes cost her dearly.

Momentum — and setbacks — going into Iowa

As the Iowa caucuses in January approached, Ms. Haley appeared to be gaining steam, despite initially struggling against competitors who had spent far more time and money in the state. She had hoped that strong performances in the early contests of Iowa and New Hampshire would lift her to victory later in her home state of South Carolina, despite its conservative tilt.

But her momentum faltered. In December, when a New Hampshire voter asked her what had caused the Civil War, she cited “the freedoms of what people could and couldn’t do” but did not mention slavery. When the questioner pointed that out, she asked him what he wanted her to say about slavery, handing ammunition to critics who accused her of telling voters what they wanted to hear.

Many independents and anti-Trump Republican voters refused to rally behind her bid, noting that she had pledged to pardon Mr. Trump if he were convicted and had not flatly rejected the possibility of serving as his vice president. Mr. Trump’s followers viewed her with distrust and skepticism for running against her former boss.

At the same time, her tight control over how she presented herself to the public also led her to bypass important opportunities. Her final public appearances were increasingly scripted, as she limited her exposure to unpredictable questions from voters.

Staying upbeat after she finished a distant third in the Iowa caucuses, she swept into New Hampshire anticipating a two-person race with Mr. Trump, and got it when Mr. DeSantis withdrew just before that contest.

Mr. Trump went out of his way to undercut and embarrass her, surrounding himself in New Hampshire with a large contingent of South Carolinians who promoted their endorsement of the former president, including Mr. Scott, whom she had elevated to Congress, and Representative Nancy Mace, whom she endorsed in 2022 over a Trump-backed primary challenger.

In South Carolina, Ms. Haley honed and increased her attacks on Mr. Trump, casting him and Mr. Biden as two “grumpy old men” out of touch with the electorate and unable to lead the country into the future.

She was defeated in her own home state on Feb. 24. But she forged ahead on a national campaign swing ahead of Super Tuesday on March 5, continuing to rake in donations even after a streak of losses. Her victories in Washington, D.C., and Vermont did make history: She is the only Republican woman to win a primary, even if the two victories totaled 36 delegates.

To those who doubted her path forward, she often reminded them that the United States “does not anoint kings.”

After her defeat in South Carolina, Ms. Haley lost the financial support of the Koch network, but she continued to draw some of her largest and most enthusiastic crowds yet. In Spring, Texas, Chris Hernandez, a Republican and a government professor at a community college, said he had come out to support her because he hoped that after all was said and done, she would continue to stand her ground against Mr. Trump.

“If I had the chance to shake her hand, and I say something to her, I would tell her that politics is temporal, history is forever,” he said. “There is a whole history of politicians putting principle over politics, and I hope she is one of those.”

On Wednesday, Ms. Haley measured her success by her parents, ending her campaign with some of the themes she began with, as she painted a picture of the United States on the brink of decline and in serious need of stable leadership. She urged Americans to “bind together” and “turn away from the darkness of hatred and division.”

“Just last week, my mother, a first-generation immigrant, got to vote for her daughter for president,” she said. “Only in America.”

[ad_2]