[ad_1]

For better or worse, the moon is officially open for business.

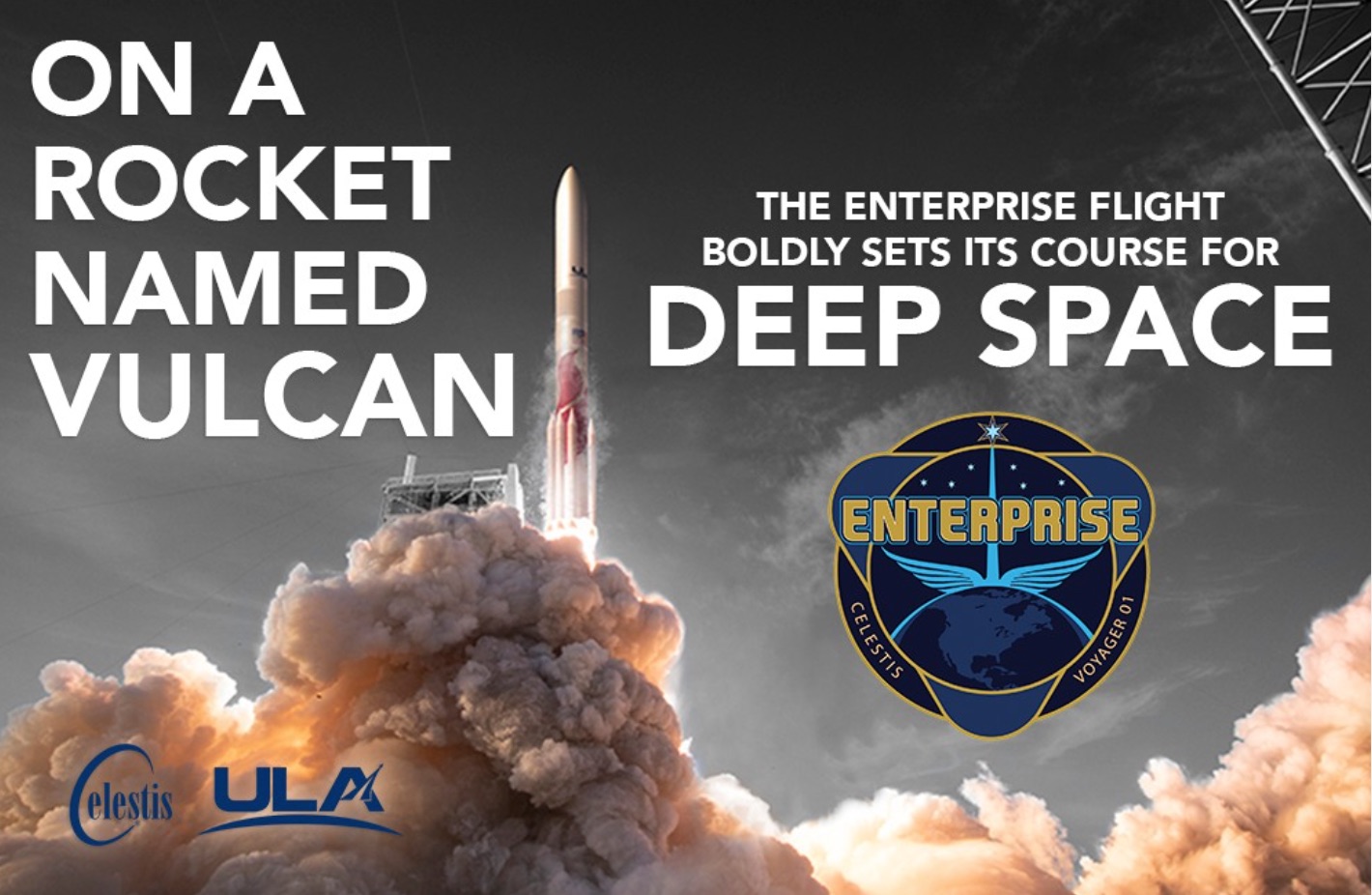

On Monday (Jan. 8), United Launch Alliance’s shiny new Vulcan Centaur rocket will launch from Kennedy Space Center in Florida carrying Astrobotic’s Peregrine lunar lander and the Celestis and Elysium memorial payloads containing human remains and DNA.

Two memorial companies, Elysium Space and Celestis, will potentially deliver a symbolic portion of remains to the surface of the moon as one of their services, with Celestis’ precious cargo of cremains and DNA riding on its Tranquility mission, the company’s second lunar flight.

A second Celestis payload will also fly on the Vulcan rocket’s Centaur upper stage to head out beyond the Earth-moon system into deep space, to establish the most remote human presence among the stars. That Celestis Enterprise Flight will include cremated remains and/or DNA material from numerous “Star Trek” icons such as Nichelle Nichols, DeForest Kelley, James Doohan, series creator Gene Roddenberry and his wife Majel Barrett Roddenberry, “2001: A Space Odyssey’s” VFX guru, Douglas Trumbull, as well as the DNA of current ULA CEO Tory Bruno, his wife Rebecca, several former presidents of the United States, and many others.

But not everyone is exactly rejoicing over the upcoming flight. As reported by Arizona Public Radio on Dec. 28, the President of the Navajo Nation, Buu Nygren, is unhappy with the notion of human remains being deposited on the moon and is formally requesting that NASA postpone this January launch due to the space agency’s promise to advise them prior to authorizing any future memorial flights.

Related: DNA from 4 American presidents will launch to deep space

In a Dec. 21 letter to NASA and the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), Nygren expressed his thoughts on the matter. “It is crucial to emphasize that the moon holds a sacred position in many Indigenous cultures, including ours,” Nygren wrote. “We view it as a part of our spiritual heritage, an object of reverence and respect. The act of depositing human remains and other materials, which could be perceived as discards in any other location, on the moon is tantamount to desecration of this sacred space.”

Nygren added that the Navajo Nation believes that both NASA and the USDOT should have consulted with them before authorizing a company to transport human remains to the moon.

However, despite the Navajo Nation’s strong objections, this technically is not a NASA-run mission. The mission will be the first launch of the Vulcan Centaur and the first mission under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which seeks to leverage private companies to help place agency-led science payloads on the lunar surface.

The mission is actually a private commercial launch by ULA and Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic Technology made possible via CLPS, and NASA has no jurisdiction over exactly what additional payloads are included.

According to Nygren, this has been an ongoing concern that “echoes back to the late 1990s, when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration sent the Lunar Prospector, carrying the remains of [geologist] Eugene Shoemaker, to the moon. At the time, Navajo Nation President Albert Hale voiced our objections regarding this action. In response, NASA issued a formal apology and promised consultation with tribes before authorizing further missions carrying human remains to the moon.”

In that particular instance, the Office of Commercial Space, operating under the U.S. Department of Transportation, was possibly negligent in failing to consult with tribes before approving the launch’s official payload certificate.

Nygren reminded parties that NASA had previously committed to notify the Navajo Nation regarding memorial flights and that the Biden administration promised to consult on tribal concerns of this nature, as outlined in the Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships on Jan. 26, 2021.

“This memorandum reinforced the commitment to Executive Order 13175 of November 6, 2000,” Nygren explained. “Additionally, the Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Interagency Coordination and Collaboration for the Protection of Indigenous Sacred Sites, which you and several other members of the Administration signed in November 2021, further underscores the requirement for such consultation.”

In a pre-launch science briefing on Thursday (Jan. 4), NASA representatives addressed the controversy over the payloads containing human remains being included on the mission. Chris Culbert, CLPS program manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, said that the private companies launching payloads as a part of the program, however, “don’t have to clear those payloads” before launch. “So these are truly commercial missions and it’s up to them to sell what they sell,” Culbert added. “We don’t have the framework for telling them what they can and can’t fly.”

NASA representatives added that an interagency group within the U.S. government is convening to discuss the Navajo Nation’s objections.

Celestis, for its part, does not find those objections to be compelling.

“The regulatory process that approves space missions does not consider compliance with the tenets of any religion in the process for obvious reasons. No individual religion can or should dictate whether a space mission should be approved,” Celestis CEO and co-founder Charles Chafer said in an emailed statement to Space.com.

“No one, and no religion, owns the moon, and, were the beliefs of the world’s multitude of religions considered, it’s quite likely that no missions would ever be approved,” Chafer added. “Simply, we do not and never have let religious beliefs dictate humanity’s space efforts — there is not and should not be a religious test.”

Correction: This story was updated at 6:21 pm ET to reflect that Celestis also has a payload of cremains and DNA riding to the moon on the Peregrine lunar lander, in addition to its payload on the Vulcan Centaur debut flight. It was updated again at 8:50 pm ET to include the statement from Celestis’ Charles Chafer.

[ad_2]