[ad_1]

To access new mates and food sources, wild mammals must often venture between protected areas. Conservationists have long advocated designating “wildlife corridors” to make this easier and safer—but the most crucial routes’ locations, and whether conditions within them support or hinder these journeys, have been largely unknown until now.

A recent study in Science found that more than 65 percent of such passages where movements are most concentrated remain unprotected. Reducing certain human pressures, the study authors note, could be even more effective at boosting connections than adding protected territory between existing refuges.

The scientists examined data on the movements of 624 individual mammals from 48 species, from South American jaguars to African giraffes, using a methodology called circuit theory to create a global map of pathways between protected areas. Most previous studies simply evaluated whether these areas were connected at all. The new study also scrutinized conditions along these mammal pathways, including routes through land used by humans for homes, crops, forestry or livestock.

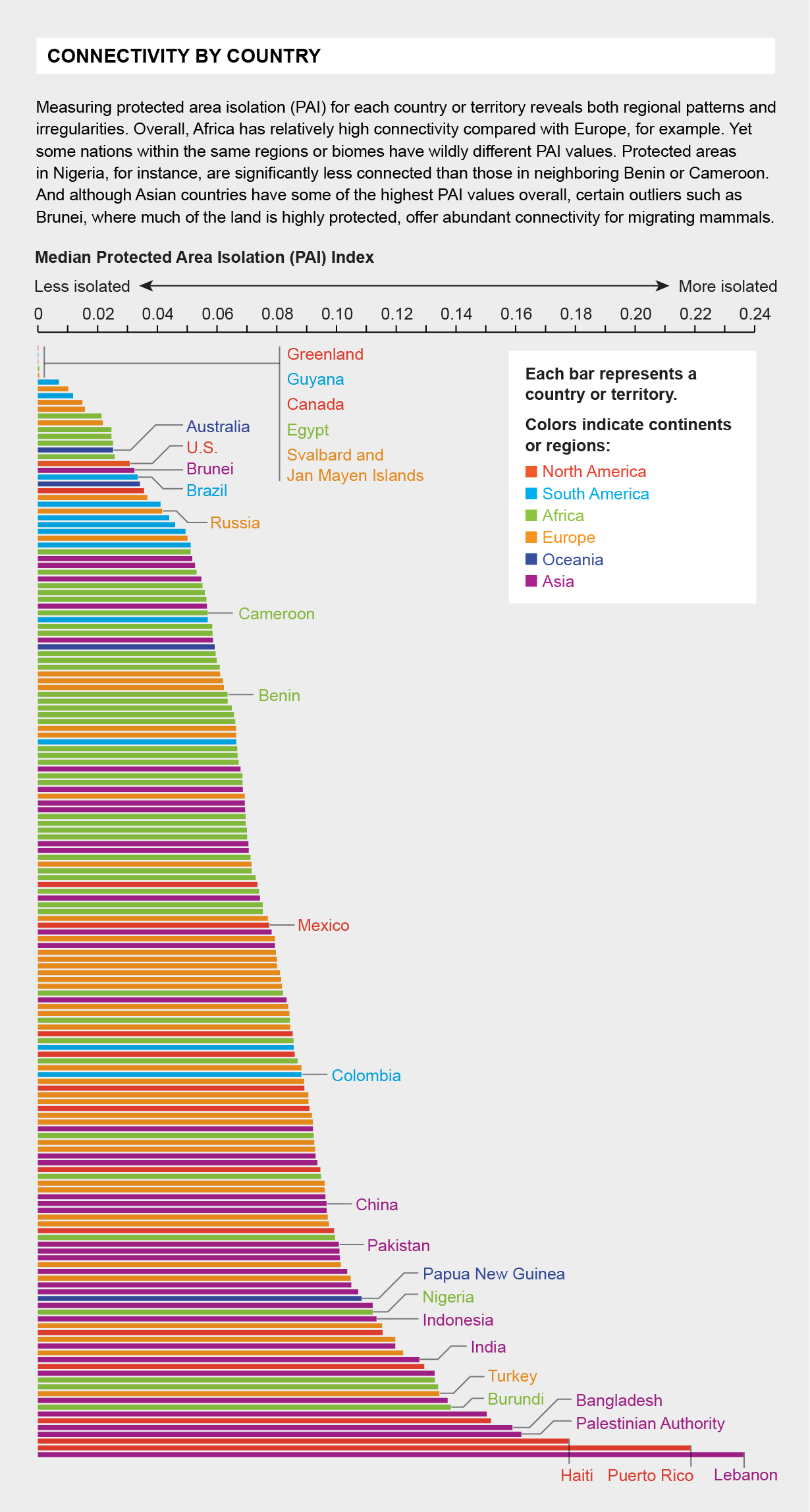

The team then evaluated whether protected areas were well connected to or isolated from others—information land managers could use to safeguard mammals threatened by habitat loss and degradation. “We need to maintain those populations and make sure that protected areas don’t become islands in a sea of human land uses,” says University of British Columbia conservation scientist Angela Brennan, the study’s lead author.

The scientists found that reducing a region’s overall human footprint by half, through steps such as minimizing agricultural use and integrating trees and shrubs into livestock areas, could increase connectivity on average by 28 percent. They also found that conserving 50 percent more land would boost connectivity by 12 percent. Together both methods could enhance protected areas’ connectivity by 43 percent.

The study uses “real data and strong analytical approaches to help us understand connectivity,” says Michigan State University ecologist Nick Haddad, who was not involved in the work. “Just improving the landscapes that are there even if people are on the land, and making them more accessible to animals, can increase the connections between protected areas.”

[ad_2]