[ad_1]

“There will be no leaving the building without an escort!” someone shouted.

Syracuse University’s London Center seethed with administrators and a few students who hadn’t boarded Pan Am Flight 103. Ringing phones shattered the night air with their keening. Those must be parents, I thought, wanting to know if their children are alive or dead.

Below us, the street swarmed with news trucks, satellite dishes craning their necks toward the dark sky. A dozen floodlights snapped on. The winter solstice, the darkest night of the year, instantly turned into a fluorescent, interrogating day.

“Here.” A woman I didn’t know handed me a list of students. The paper was frayed around the edges, an old attendance sheet awaiting grades to be handwritten in the boxes next to the names.

“I need you to check off the students you know were on the flight and those you know weren’t,” she told me and then disappeared as quickly as she had appeared.

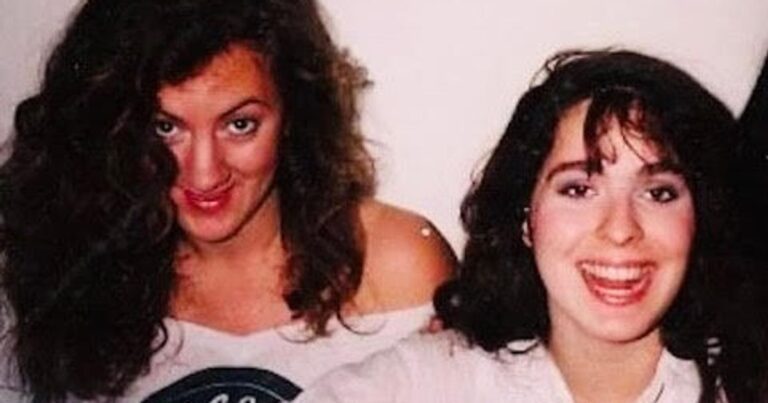

I scanned the list. My friends began to rise off the page, lofted by memories from only hours ago: the smell of last night’s beer on Turhan’s breath, Luanne’s chipped pink nail polish on her fingernails clutching a plane ticket, Miriam’s high-pitched sneeze into a handkerchief, the way a strand of Theo’s long black hair caught briefly in my eyelashes as she left my arms to run and join the others in the cab. Turhan Ergin. Luanne Rogers. Nicole Boulanger, Miriam Wolfe, Wendy Lincoln, Daniel Rosenthal, Theodora Cohen. Theo — my best friend.

I concentrated and then began placing check marks where their grades should be.

Meanwhile, 300 hundred miles away, the town of Lockerbie, Scotland, was burning.

Thirty-five years ago today, a bomb exploded aboard Pan Am 103 heading from London to New York, killing 259 people, including 35 of my classmates, as well as 11 townspeople on the ground.

I was a junior studying abroad in London. I should’ve been on that plane too. A few months earlier I had begun having nightmares about planes exploding. The dreams gave me panic attacks, and I was convinced I would soon be dying on a plane. Theo pleaded with me to change my flight back to the U.S. so she could hold my hand but, in the end, I lacked the money to pay for the change fee. Now she was dead, and I was barricaded in this cramped office by walls of cameras and reporters outside, and mocked by the Christmas decorations strung up around me.

At the time of the terrorist bombing, a young constable named Colin Dorrance was speeding toward Lockerbie on his way to a holiday party. As he approached the town, he heard what sounded at first like deafening thunder. Then he saw a massive explosion and flames billowing up 300 feet in the air. Colin pulled his car over and ran to the site, and he found a vast crater where several houses had stood just moments earlier. The heat kept him from getting too close, and the air was thick with jet fuel. He was one of the first people at the crash site.

Courtesy of Colin Dorrance

Three miles away, the nose cone of the plane landed in a field — no fuel, so no flames, but just a thud and a scattering of its contents. Then, across 25 square miles, thumping could be heard. Bodies fell from the sky and landed in fields, in gardens, on roofs, in trees, in children’s sandboxes, on roads and in ditches. It also rained clothing, suitcases, glasses, hairbrushes — the memorabilia of life like confetti whipped up by the wind — and Christmas presents, hundreds of them, as if Santa’s sleigh had been tipped upside down across all those miles.

Hours later, Lockerbie was overrun by press, military and fire brigades. Colin was asked to oversee the side door of the town hall, which became the headquarters of the emergency operation. Not long after he was positioned there, a farmer pulled in with a pickup truck filled with plane debris. A police sergeant offered to help him unload the truck and when they finished, Colin saw the farmer point to the front seat where the body of a 2-year-old child was wrapped in a blanket.

“I didn’t know what to do,” the farmer said. “There are other bodies. All about my farm. Hard to tell in the dark. Thought I should bring the child here.” The sergeant reached in and took hold of the limp body. The chiseled, worn face of the farmer was visibly shaken.

When the sergeant and Colin arrived inside the great hall, everyone stopped and the entire room became silent. The sergeant carried the body to the far corner of the hall and laid her down on the shiny gym floor. No one spoke or moved for several seconds as everyone took in the sight of that tiny, lifeless body in that vast, chaotic space. It was the first body of dozens that would eventually fill the room.

As dawn arrived the day after the bombing, I was taken to the airport to catch a flight home. Still in shock when I arrived, I could not move my body. Someone fetched me a wheelchair.

I was barely in my seat on the plane when an airline attendant approached me.

“Miss, can you follow me and bring your stuff?” She led me and another young woman from Syracuse to the front row of first class, just behind the cockpit door. The pilot came out, knelt in front of us, and took our hands.

“When I heard you two were on my flight, I asked for you to be moved so I can check on you and make sure you’re OK,” he told us. “The pilot of that Pan Am flight was a close friend, and I am the godfather to his children …” He stopped himself and took a moment before continuing: “I want to promise you that I’m going to get you home safely. If you need anything, please just let someone know.”

With that, I felt him squeeze my hand and he returned to the cockpit. How that man flew that day, over what was surely Lockerbie still visibly burning, I will never know. I replayed that encounter almost every day for months, and remembered his strength and kindness as I struggled with my own path forward.

After the bombing, the people of Lockerbie and Scottish law enforcement officials undertook the task of continuing to recover passengers’ bodies and collecting every item they could find strewn across and around the town. Many of the women who lived in the area baked food for the service members and then turned to salvaging, sorting and cleaning any of the retrieved personal items, so they could be returned to the victims’ families. Colin worked day and night carrying bodies, guarding sites against vandalism, and scouring fields, looking for relics of the dead. Though they were grieving the loss of 11 members of their community — and the unspeakable tragedy itself — so many of Lockerbie’s citizens selflessly gave their time and energy to help bring closure to people they would likely never meet.

But, as it turns out, many of us who lost friends and family in the bombing ended up making deep connections with residents in Lockerbie.

It took me 30 years to visit the town. Unlike others who went soon after the tragedy, I could not face it. For me, Lockerbie was a place perpetually on fire, with bodies hanging from buildings — a town made up of only darkness and pain. Instead, I tried to escape the inescapable. After I graduated college, I fled across the country from Syracuse to Seattle, where I didn’t know a soul, in hopes of starting over in a place where I would be nameless. However, the attack followed me.

On the fifth anniversary of the bombing, while working in Pike Place Market, I walked by a newsstand displaying the latest issue of Time magazine. On its front cover was a photo of the plane’s now indelible nose cone crumpled in the field outside Tundergarth Church. I immediately fell to the ground and sobbed.

On the 10th anniversary, I traveled to the D.C. area to stand numbly among grieving families and pontificating politicians in front of the Lockerbie Memorial Cairn at its dedication in Arlington National Cemetery.

I spent years tormenting myself by believing that the nightmares of plane crashes I’d experienced in the months before the attack were trying to tell me something and that I had been too self-centered to listen.

Milestones continued to pass, and friends suggested a trip to Lockerbie, but I refused to go until the 30th anniversary. As I, once again, listened to news reports about the geopolitical aspects of the bombing and its perpetrators, I felt my anger explode. I knew it was time to share the stories of some of the victims of the attack and those who were left devastated in its wake. I also knew I finally had to face the place that still held so much darkness for me.

Courtesy of Colin Dorrance

Thankfully, a friend who knew how reticent I had been about going to Lockerbie connected me to Colin. His reputation for being caring had only grown in the three decades since his service at the bombing site, and in recent years he had been kind enough to give tours of the area to families and friends of the victims. He agreed to show me and my daughter (who, ironically enough, would end up attending university in London) the area as well.

Colin welcomed us warmly, and for two days he drove us to different sites around Lockerbie. He even put us up in his home, where we enjoyed a warm meal and a night of laughter with his wife and two children, and I experienced hours of unexpected joy in a place I thought only held sorrow. Colin and I were now both parents, with children the same age as my friends when their lives were taken. And thanks to the clarity that comes with age and experience, we both held a new understanding of what had been lost on that night so long ago.

Before we left Lockerbie, we visited the town hall. It had new shiny wood floors and tall, arched windows stretching almost two stories above the gymnasium. A few people were bustling about, putting the final touches on decorations for a wedding that day — nothing especially ornate, but obviously an event that would be full of love.

“Forgive me, it’s tough for me to step inside this room, even today,” Colin said as he stopped himself from crossing the threshold. His voice caught in his throat. He had spent many days there carrying bodies — babies, whole families, students from Syracuse — and laying them in wooden caskets. As we stared into the room in silence, questions flooded my mind: When was Theo carried into this room? Was the earring she borrowed from me before she boarded the plane still in her ear? Who laid Miriam down in her coffin? Was her curly hair covering her face? Who processed Daniel’s lanky body? Did he still have glasses on? Where would they have put Turhan’s hand — the only part of him that they found, which I had high-fived hours before he boarded the plane? Did someone jot down a note next to Nicole’s name when she was officially declared missing?

I could only hope that at least one of them had been cared for by this gentle soul at my side — this man who would welcome me back into his home again and again in the following years, spend hours with me on Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic as I worked to intertwine my story with his on paper, make me laugh with his silly jokes, and support my husband when he traveled to Edinburgh to perform. He also offered his help if my daughter ever needed anything while she was at university, a gesture that felt especially kind now that I was the parent waiting for my child to fly home for Christmas along that harrowing path I faced 35 years ago.

In that moment in the gym, with Colin standing beside me outside its door, I felt a sense of peace that I hadn’t felt since before the bombing. There were no words needed — not to explain, not to console, not to try to make sense of the madness and grief and guilt that had followed me for so many years. We could just exist in silence as our stories both collided and fell beside each other’s lives. I had spent so many years in isolation because I thought I deserved to be alone, but I suddenly understood how wrong I’d been. Though Colin’s experiences and journeys were different from mine, we had been through something that few other people could ever understand, and having him in my life made me realize that others were grappling with similar emotions. Most importantly, I saw that community and closure were possible.

I have been haunted by what happened in Lockerbie for most of my life. I didn’t want to go back because I thought that all I would find there was more of the terror and the pain I already carried with me. Why would I want that? But sometimes facing our nightmares is the only way to end them. And thanks to my family and friends, Colin, and so many of the other people I met in the last five years, I realized that I wasn’t alone. Holding on to Colin’s arm as we watched that wedding come to life in that room that once held so much sorrow, I knew with the help from the people I love, I could finally begin to heal.

Annie Lareau is a Seattle-based actor, director and writer who spent the last eight years as the artistic director of Seattle Public Theater. She holds a BFA in theater from Syracuse University and an M.Ed. from Harvard University. Her writing has been seen on the stage through adaptations of novels including “Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet” by Jamie Ford and “My Ántonia” by Willa Cather. She is currently in the revision process of her memoir about her journey following the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 and is embarking on her first novel, set in Key West in the 1980s. For more info, visit her website, www.annielareau.com.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

Support HuffPost

At HuffPost, It’s Personal

[ad_2]